15 Nov. 2018 : Malek Bensmail was a guest at the festival des cinémas d’Afrique du pays d’Apt where he participated in a masterclass, moderated by Olivier Barlet, during which he discussed his work as a documentary maker.(texte en français ici)

Why choose to make documentaries ?

Actually, like every young algerian filmmaker, I wanted to do fiction. But after a short training in Paris, that was quite theoretical, I had the opportunity to spend a year in Russia, at the Lenfilm studios, in what used to be Leningrad, and is now called Saint-Petersburg. It was a revelation. We had to go through every step of creating fiction, from writing to directing. So I was in touch with Alexei Guerman and Alexandre Sokurov. It was during the Gorbachev era. We often discussed what was going on at the time; the way that the world was changing, we also talked about Algeria. They wondered why there were no documentaries that informed them about Algeria. Sokourov found it surprising that a former revolutionary country didn’t have any documentary schools. 1988, that was when the first revolts against the regime happened. They were led by the Algerian youth and they were repressed by the army (500 people died). Then little by little, came the beginning of multi partisanship, the islamist parties and the so called “black decade”. And that’s when I did my first work…

What you documented in Algérie(s)?

Yes, afterwards. My first work was an experimental film called Territoire(s), about what I call the archaic violence in Algeria, it’s a very raw violence, very physical, but also psychological after a while. It’s a postmodern violence. It’s also about the way that the western world looked at this violence, which is the same way they look at violence nowadays in Syria, for example. The movie is half an hour long, very experimental, it truly is an editing film, about confrontations between archaic violence and the postmodern violence from the international media, that doesn’t have a simple name for it. I took as a basis for my work both what I already knew about my society, but also of what I had begun to read, what I had been lacking; philosophers, the Quran, algerian proverbs. I dove into the society that I had left to follow my studies. I also used Paul Virilio’s work, he did a tremendous work on speed and accidents: in video games, where everything is so fast and you’re shooting people, but also the capitalist financial crash. At the time, this archaic violence that existed nowhere else was rising, and that was long before 9/11.

Yes, afterwards. My first work was an experimental film called Territoire(s), about what I call the archaic violence in Algeria, it’s a very raw violence, very physical, but also psychological after a while. It’s a postmodern violence. It’s also about the way that the western world looked at this violence, which is the same way they look at violence nowadays in Syria, for example. The movie is half an hour long, very experimental, it truly is an editing film, about confrontations between archaic violence and the postmodern violence from the international media, that doesn’t have a simple name for it. I took as a basis for my work both what I already knew about my society, but also of what I had begun to read, what I had been lacking; philosophers, the Quran, algerian proverbs. I dove into the society that I had left to follow my studies. I also used Paul Virilio’s work, he did a tremendous work on speed and accidents: in video games, where everything is so fast and you’re shooting people, but also the capitalist financial crash. At the time, this archaic violence that existed nowhere else was rising, and that was long before 9/11.

Territoire(s) went around festivals; a few networks bought it, the BBC for example, for their experimental programs. A lot of museums bought a copy. That’s when I decided not to limit myself to the experimental genre, nor explore fiction, but rather to focus on documentary films. After the first film, I needed to question the themes that were important in my society, layer by layer. There is almost everything in that film, in half an hour. Violence, the topic of language, since we had been told to use Arabic, the topic of God, the school system… a patchwork made of images. Sometimes, I see this film as what inspired the work I made after.

Territoire(s) went around festivals; a few networks bought it, the BBC for example, for their experimental programs. A lot of museums bought a copy. That’s when I decided not to limit myself to the experimental genre, nor explore fiction, but rather to focus on documentary films. After the first film, I needed to question the themes that were important in my society, layer by layer. There is almost everything in that film, in half an hour. Violence, the topic of language, since we had been told to use Arabic, the topic of God, the school system… a patchwork made of images. Sometimes, I see this film as what inspired the work I made after.

And you wanted to very quickly question politics.

Indeed, because those were the beginning of very difficult times. For example in 1999 I made Boudiaf un espoir assassiné: in ‘92 our president was murdered on live TV. It was a way for me to touch on the subject of the mechanics of power but also to learn how to put into place what we call a historical perspective: “Who is this person, why did they bring him back ?” Then, as time went on, I chose different themes. Perhaps I needed to build a home, a memorial home. When I was a child, there were a lot of lies inside our society, in what we were being taught, in my family maybe, but also in the streets. We overprotected our ideology, the FLN party, etc. Everything was counted as 1, 1 God, 1 political party, 1 people, 1 language, but we are the Arabic world, creator of 0 to 9. I wanted to know the other numbers and therefore work on the question of linguistics, our relationship with how we look at ourselves, to look at ourselves in the mirror, to film madness in psychiatric hospitals, the school, the press, etc. I wanted to document my country in a deeper way with each film, with a strong thematic but always through a prism that allows you to see yourself.

Indeed, because those were the beginning of very difficult times. For example in 1999 I made Boudiaf un espoir assassiné: in ‘92 our president was murdered on live TV. It was a way for me to touch on the subject of the mechanics of power but also to learn how to put into place what we call a historical perspective: “Who is this person, why did they bring him back ?” Then, as time went on, I chose different themes. Perhaps I needed to build a home, a memorial home. When I was a child, there were a lot of lies inside our society, in what we were being taught, in my family maybe, but also in the streets. We overprotected our ideology, the FLN party, etc. Everything was counted as 1, 1 God, 1 political party, 1 people, 1 language, but we are the Arabic world, creator of 0 to 9. I wanted to know the other numbers and therefore work on the question of linguistics, our relationship with how we look at ourselves, to look at ourselves in the mirror, to film madness in psychiatric hospitals, the school, the press, etc. I wanted to document my country in a deeper way with each film, with a strong thematic but always through a prism that allows you to see yourself.

For you, to document Algeria meant creating archives, not in an old fashioned way, but rather as a means of generating a future. They are contemporary archives, made with and about the present, and looking at the future. These are stakes that can be perceived throughout all of your films.

Yes, it’s probably to fill in a gap. Something that is missing. We are so out of touch with the truth. Documentaries don’t really exist in Algeria, beside propaganda movies about the revolution during the Boumediene presidency, or movies about the language… a message to send to the population. True documentaries, as in films about our society, with sociological, political or societal themes, they didn’t exist. Without knowing, I felt the need to fill a gap, for me, for the public, and so my children could know the depth of this country, its temporality. By seeing those films, you can understand what happened in 92, 93, 94, 96… I’m marking time to fill in the gaps. There is a global amnesia surrounding the truth about the Algerian war, as well as the 80’s and 90’s. And once we entered the bloody decade, it became an undocumented war. I was amongst the few who tried to make films during this period.

Films about the revolution were fictions, anyway.

Yes, they were. One or two documentaries existed, but in general, most movies were like Le Vent des Aurès, they were great dramatic paintings, not allowing us to see beyond the myth of the hero. I was interested in anti-heroes, in the population, in anonymous people !

Territoire(s) and Algérie(s) both have an « s” in parenthesis. Was it to distance yourself from an entity with a capital “A”, to highlight diversity? It’s a similar approach to the one used by young filmmakers such as Karim Moussaoui, who wanders around a diverse Algeria in En attendant les hirondelles.

Yes, the “s” was as important to me then, as it is now. Even with Contre-Pouvoirs, the plural matters because there are different voices. We remained on one base for 50/60 years, and we’re still standing on it today, even though the people, the culture, the language and the points of view are very diverse in Algeria.

Algeria is five times as big as France. Despite that, we always film the same spaces, the same people. For example, no one is filming black people, even though they make up half of the population as soon as you go down south. In the Algerian iconography, there are no black people. I wanted to start with that fact; there’s one kind of TV, one kind of cinema, one kind of regime, and from that, go towards a diversified population, deeply human and open, a population that questions itself. I don’t have enemies, in my opinion an islamic extremist isn’t an enemy. You have to try to understand how he works. What drove him to this point? There must have been something crazy handed to him, to make him shift towards this path.

In the text that comes with Contre-pouvoirs, there’s a quote from Kamel Daoud: “counter power is a place of disobedience, not a counterweight like in democracies, it resists uniforms and therefore standardization” We’re truly following this idea.

Exactly. Even with Contre-pouvoirs, it wasn’t about making THE portrait of El Watan, even if it is an immersion inside its core. It was a gathering of all the small counter-powers that are these journalists, who all have totally different opinions, and yet still work at the same paper. I think there might be a democratic success at this paper that doesn’t exist in our society.

Which is quite troubling. After seeing their debates, one can wonder how they manage to write together.

And yet, they manage, and everyone has their space. But they have real debates and they truly listen to one another.

What is striking, and is in other films as well, is how lively these debates are, a kind of research lab, where nothing is fixed. Is this what we can hope and envision for Algeria in the future?

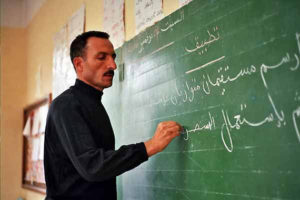

We often talk about hope, and we have to, of course, but I don’t care about this kind of hope anymore. I think there’s a real life. The people I film have a very proactive life, despite the climate of global depression that exists in Algeria, we know why. But there is still a society that is alive, moving, and has its struggles obviously. It knows that there’s not much hope, but those people who write the papers, the doctors in the psychiatric hospitals, the teacher, the kind who does a great job like in my film La Chine est encore loin, they all keep doing their job in a country where daily life is really hard. But they carry on because they can’t make a different choice than the choice of living.

You always shoot with a light crew, it allows you to both have realistic budgets but also to see and have a relationship with the people you’re filming? The question of the right distance to keep seems to be at the center of your work.

To answer your question, I have to add to the topic of making documentaries. I think it shouldn’t just be about observing and capturing a moment. It has to have a social impact, it should be a tool to measure democracy so I can know where and how far I can go. It allows institutions which had never let a camera in before, to slightly open their door. It is important that powerful people know that it’s possible to film their work without using it against them. It can be of interest for them too. It needs to be explained to them. Cameras are considered to be dangerous by administrations because they are used to gather evidence. You have to explain your process and work with a small crew. Usually it’s just me filming except for big interview films like La Bataille d’Alger, un film dans l’Histoire. I always have a sound engineer and a director of photography but I’m usually the one doing the framework. I have an assistant sometimes but he always keeps out of the shooting space, we can’t have more than two or three people on site, so we can create a strong relationship and explain better. Especially in our society, documentary filmmaking is a space where we must be very educational and explain everything: it’s necessary that the person being filmed can say if they no longer want to participate in the film. We don’t make people sign a contract like they do in the West. As soon as the person says yes, you have to be willing to show them the rushes. Even if they don’t like something, if you explain it to them, they might agree to carry on. But there have been times when the person said they didn’t want to be in the film anymore. It’s a process that makes you face yourself. I don’t want them to feel betrayed after having agreed to do it.

Do you have strict criterias when filming ?

No. To film a mentally ill patient is not the same as filming a child or a powerful man. The perspectives are completely different. Again, you have to explain everything, even to someone who is mentally ill. With Aliénations, I had access to rooms where patients were being treated, and they had no idea I was filming. I went to see the doctors, saying: “they have no idea that I’m filming, it isn’t okay, find patients that look like us, who can at any moment push me and the camera away and who have the ability to say that they don’t want to be filmed anymore.”

No. To film a mentally ill patient is not the same as filming a child or a powerful man. The perspectives are completely different. Again, you have to explain everything, even to someone who is mentally ill. With Aliénations, I had access to rooms where patients were being treated, and they had no idea I was filming. I went to see the doctors, saying: “they have no idea that I’m filming, it isn’t okay, find patients that look like us, who can at any moment push me and the camera away and who have the ability to say that they don’t want to be filmed anymore.”

It is often said that “what’s real resists.”

That’s it. It is crucial that reality disrupts my first intentions entirely, or for other characters to appear even though I hadn’t thought of them. That’s what I like, because it’s stronger than fiction where almost everything is written down and planned. Except for those who work like Kiarostami does, starting with 3 or 4 pages and then writing the script as they go. But overall, when it comes to documentaries, you have your topic in mind, the outlines, the intentions, with the possibility that it might all be changeable. Once you get to editing, you need to be challenged by the rushes. “Why did I put the camera there ? What made me stand there ? Was it a problem on set ? There was a woman who I knew had a problem with the camera.” You ask yourself a ton of questions, and it leads your film to evolve, and you to question every step you make. It’s crucial, that’s how you get to a draft as modest as possible, to something that is more than just what you observed.

So it is a constant production.

Yes, the distance you put or the axis you use isn’t chosen only during the writing or the shooting, but all throughout the making of the movie, up until the first draft is made. Even colorimetry or calibration can allow you to put some distance, strengthen or darken an image, therefore or a character. The cinematic language but also its technique and tools of filmmaking allow us to accompany the characters the best we can. If I had to give only one answer, it would be the idea of closeness with the characters but to let them have a bit of mystery as well. They keep evolving. Even for interview movies, I try to edit my documentaries like thriller movies, so there’s always a part of drama and a study of characters in a cinematic way. Even in a classic interview situation, there’s a narration where the characters evolve from point A to B.

In film school, they teach you to slowly zoom in during interviews, to give depth. Is it a rule that you use ?

It really depends. For example, shooting Contre-Pouvoirs has been harder than shooting my other films. Why? Because I was filming journalists and intellectuals. Journalists master the art of image control, and their fear of being filmed is a lot stronger than the one someone who comes from the street or a village can feel. Things can be very complex for those who are familiar with how cinematography works, or with the documentary process. Yes, you could say that we’re going slow, or the opposite, we’re being direct right from the start, it depends on the subject you’re treating. But the starting point is the respect you have for the other person. And the most important thing for me, is to be a listening ear. Not just a gaze, but truly a listening ear, because Algerians have, when you know how to talk to them, a true desire to speak and share a testimony. It’s because there has been a lot left unsaid, there’s a lot of guilt and bitterness. But also plenty of joy and a lot of Algerian humour! You have to let things go and work by levels, and as soon as they trust you, anything is possible.

The first part of Algérie(s) was entitled: “a voiceless people.” It reminds us of Deleuze: “the people are missing.” The population isn’t seen because it isn’t allowed to speak. The intimate voice is hard to catch…

Yes, and to succeed I think that what matters most is my approach, to engage the character by telling him, “I’m not making a film about you, but with you, and we have to do this film together.” They have to understand that as a filmmaker, I can have weaknesses or doubts. And that is why I don’t want more than one camera, or a big crew: the person you’re filming has to see that you too, can be fragile. If I’m not able to follow them, they should be able to say “do you want me to do it again?” They have to understand that we’re not only making a film to look at a subject that is important to me, but also to them. We share a slice of life together on set. You also have to quickly show them the rushes, to make sure there is a continuity. I’m thinking in particular about the teachers in La Chine est encore loin, where the Arabic language teacher saw that he was tough with his students. After seeing the rushes, he said to me, “I don’t want to carry on because you’re not filming me right.” I explained to him that I was only filming him the way he was presenting himself. I’m not trying to trap the characters, on the contrary I would like my camera to allow them to evolve. Even in Contre-pouvoirs the journalists learned how to change their speeches. Even if things don’t always go the way I would have liked, I’d rather accompany them than steal things that would then have negative consequences on people’s lives.

Yes, and to succeed I think that what matters most is my approach, to engage the character by telling him, “I’m not making a film about you, but with you, and we have to do this film together.” They have to understand that as a filmmaker, I can have weaknesses or doubts. And that is why I don’t want more than one camera, or a big crew: the person you’re filming has to see that you too, can be fragile. If I’m not able to follow them, they should be able to say “do you want me to do it again?” They have to understand that we’re not only making a film to look at a subject that is important to me, but also to them. We share a slice of life together on set. You also have to quickly show them the rushes, to make sure there is a continuity. I’m thinking in particular about the teachers in La Chine est encore loin, where the Arabic language teacher saw that he was tough with his students. After seeing the rushes, he said to me, “I don’t want to carry on because you’re not filming me right.” I explained to him that I was only filming him the way he was presenting himself. I’m not trying to trap the characters, on the contrary I would like my camera to allow them to evolve. Even in Contre-pouvoirs the journalists learned how to change their speeches. Even if things don’t always go the way I would have liked, I’d rather accompany them than steal things that would then have negative consequences on people’s lives.

Editing dictates a point of view. How do you approach that? You always work with the same editor.

Yes, Matthieu Bretaud.

For your latest films as well?

Yes, even for La Bataille.

A relationship with an editor is always sensitive.

It’s like a couple, that’s true. It can be good to change things up sometimes. But Matthieu is a person who learned Algerian Arabic. He had a notebook and was writing in it. He really figured out the way Algerian people move and carry themselves. He has a good feel of how to edit. It’s like a treasure, you can’t lose it ! If you do, then you have to explain how things work all over again, to a new editor, or you would have to hire an Algerian editor, and there were not a lot of them back in the day. Now, thanks to a few trainings, there’s a new generation coming, and they have potential. But at the time when everyone was leaving Algeria, it was very hard to form a team. Editing is very important because that is when you question your rushes. You pull out 150 hours of rushing and put them on the table… there is no construction plan from the start. Of course, there’s a thread: to make the audience understand that I’m not familiar with the space I’m going in. Somebody has to introduce me to it. La Chine est encore loin and Alienations both start with a long tracking shot before going inside. This allows me to keep the spectator at a distance and to make them enter at the same degree as myself, with time. Together we take the time to understand what’s happening on the inside.

It’s like a couple, that’s true. It can be good to change things up sometimes. But Matthieu is a person who learned Algerian Arabic. He had a notebook and was writing in it. He really figured out the way Algerian people move and carry themselves. He has a good feel of how to edit. It’s like a treasure, you can’t lose it ! If you do, then you have to explain how things work all over again, to a new editor, or you would have to hire an Algerian editor, and there were not a lot of them back in the day. Now, thanks to a few trainings, there’s a new generation coming, and they have potential. But at the time when everyone was leaving Algeria, it was very hard to form a team. Editing is very important because that is when you question your rushes. You pull out 150 hours of rushing and put them on the table… there is no construction plan from the start. Of course, there’s a thread: to make the audience understand that I’m not familiar with the space I’m going in. Somebody has to introduce me to it. La Chine est encore loin and Alienations both start with a long tracking shot before going inside. This allows me to keep the spectator at a distance and to make them enter at the same degree as myself, with time. Together we take the time to understand what’s happening on the inside.

Editing is also about making choices….

Yes, but I really enjoy editing because you can work on what is called elasticity. I like to have different sorts of pacing throughout a film, depending on each theme and character. You work with both time and space. Sometimes you pull on that elastic band, so that the pacing can breathe, so there is time to look at the bodies and the doubt. And then sometimes that band is smaller, you center in on an action that allows you to show how strong, violent and tough this specific moment can be. I like to oscillate between the two, it depends a lot on the film.

Let’s watch an excerpt of Des vacances malgré tout (2000), where the topic of elasticity is represented. In this movie you’re with a family that you don’t really know, an Algerian family who lives in France and is building a vacation house in Algeria, to visit during the holidays. There’s a confrontation between the Algerians who live in France and the family who lives there. You didn’t get a permit to film so you were restricted to a private location.

As it turns out, the fact that I didn’t get a filming permit forced me into a home movie process. A member of that family was a key grip on one of my films and he told me about his father who had been sending money to his brother since 1962, to build a house. So we took a small camera, I pretended to be part of the family, and we left by car, with the camera hidden in the microwave and the mics in the rugs! We were using tapes at the time, and we hid them among the girls dirty laundry on the way home, because we knew customs wouldn’t go through it. [Excerpt]

As it turns out, the fact that I didn’t get a filming permit forced me into a home movie process. A member of that family was a key grip on one of my films and he told me about his father who had been sending money to his brother since 1962, to build a house. So we took a small camera, I pretended to be part of the family, and we left by car, with the camera hidden in the microwave and the mics in the rugs! We were using tapes at the time, and we hid them among the girls dirty laundry on the way home, because we knew customs wouldn’t go through it. [Excerpt]

I picked this excerpt because it shows that the family was implicated in the filming process: we can see the son recording sound and I believe that you gave the camera to one of the girls at some point.

Not in this clip, it was when they went to the beach.

Because of that, the people you’re filming are truly involved in the creating process, which is quite rare in your body of work. Why do it for this movie?

It’s simple. From the moment I knew I wouldn’t be shooting in an official way, I had to reinforce the home made movie process. Therefore, I had to make use of it and truly include the family. So I lived with them, I witnessed their dramas and their fighting. Just before we left I briefly taught my friend how to record sound, and he became the boom operator during his own holidays. We had to be fast and react quickly, have a camera by my side at all times. That’s how we got some rushed looking shots. As for editing, it was hard for Matthieu, he had to find splices.

The editing is dynamic, switching between close-ups and inserts, and the film itself you described as rushed.

It’s a very dynamic family, they are all over the place. They don’t listen to each other, everyone is speaking at the same time, words get tangled… It was hard because I was the only one filming: I had to work on focus, and the auto-focus didn’t work well because there were so many of us. The sound tech wasn’t a real sound engineer, he lost a lot of footage, cuts had to be made. Technically, it was complicated, thus a lot of inserts.

I picked this excerpt for a second reason; the case of women, which hasn’t been a main theme but still is in a lot of your movies. I remember interviewing René Vautier during the “black decade” and we talked about the terrible situation happening in Algeria. He told me then “The Algerian revolutionary groups had a way of keeping women to a limited role. No one pointed out how dangerous it was for the country’s evolution. I couldn’t properly share the stories that those women had told me, maybe because I was different, as a foreigner. I was told it wasn’t the right time, and I believed it too. I realise now that it’s too late, I should have shared those stories.” Rachida Krim has made a very strong movie about it: Sous les pieds des femmes.

Yes, René Vautier’s answer is very good. You can still see it happen nowadays. It’s very paradoxical. The family code places them under the authority of the father or the older brother, it’s a complicated heritage. But at the same time, it’s thanks to women that society is surviving today. It’s thanks to women, who were so brave, that the war was won. It’s thanks to women that fighters were able to go to the maquis and get food supplies. There is no equality for them but they are the one handling society. I’m filming women in the situation that they’re in today. They are doing an exceptional job, but they don’t have equal pay, even when they’re doctors. They are fighting an internal fight a lot harder than you can imagine.

We are now going to show an excerpt from Aliénations (2004), shot in a psychiatric hospital. [Excerpt] You’re not filming madness itself here, but rather how society creates madness.

This excerpt is still relevant today! It’s very common. It’s mental illness, but then again, it’s not. They go to the doctor because it’s the only way they can speak, express themselves, and to have someone listen to them. Because in this society, nobody is listening to them, justice isn’t listening, administrations aren’t listening, it’s the same thing to have state housing. There comes a point when the only person you’re going to be able to see is a psychiatrist. Moreover it’s someone who is going to give you medicine that will allow you to relax. It’s either that or drugs. It’s called emergency psychiatry, because society is under pressure. It talks about corruption and the relationship with the State. In Aliénations, 90% of people’s delirium were due to political or religious matters. The hospital is like a breath of fresh air, to unwind a bit.

This excerpt is still relevant today! It’s very common. It’s mental illness, but then again, it’s not. They go to the doctor because it’s the only way they can speak, express themselves, and to have someone listen to them. Because in this society, nobody is listening to them, justice isn’t listening, administrations aren’t listening, it’s the same thing to have state housing. There comes a point when the only person you’re going to be able to see is a psychiatrist. Moreover it’s someone who is going to give you medicine that will allow you to relax. It’s either that or drugs. It’s called emergency psychiatry, because society is under pressure. It talks about corruption and the relationship with the State. In Aliénations, 90% of people’s delirium were due to political or religious matters. The hospital is like a breath of fresh air, to unwind a bit.

What’s extraordinary is that people tell you to film by saying: “show it to all of Algeria.”

There is a relationship with speaking up. It comes back to my point about democracy that is achievable through the camera, where someone can truly express themselves and go through with what they want to say. No one is listening to them. They know that the television is manipulated, that the news is manipulated. This creates an illness in Algerian society, a very strong moral and psychological misery.

What’s more, it’s a rather personal film because your father was a psychiatrist. It’s in the same hospital where he practiced, no?

Yes he did, and he’s the reason it was built in the first place. My father was one of the founders of Algerian psychiatry. First, he was in charge of the psychiatric wing of the Constantine E.R, and during Boumediene’s term, he asked for a hospital to be built, one with behavioral therapy, and a room to host parties or play chess with patients, etc. It was a long fight. Boumediene had said to him “There is no mental illness in Algeria.” The government considered mental illnesses to be a western creation.

Now, let’s watch an excerpt from Le Grand Jeu (2005) about Ali Benflis’s campaign for the presidential election. He was an opponent to the regime, to the FLN and Bouteflika. I’ve chosen this excerpt because right after filming him as he was stonewalling in his car, you get to his meeting and you film the crowd without turning it into a propaganda movie. The people here are active but not complacent.

Some credit must be given to Benflis because to this day, he’s been the only politician to ever accept a camera. It was a long process, but he agreed to it and gave me total freedom. I needed him to make this film, as much as he needed me to make it. To have a trace of it, or to explain what he was trying to do. So I was able to film some amazing things. We travelled 40,000km in Algeria, went to meetings everywhere. I’m wondering how he manages to have three to four meetings a day! I was very tired myself. I could get to a man who was truly alone. The film is called Le Grand Jeu because the population doesn’t exist in this kind of democratic process. It’s just a stop on the way to please those who are powerful and their chancellery. We know that this kind of opponent is in total solitude. He knew perfectly well that he was being used.

Some credit must be given to Benflis because to this day, he’s been the only politician to ever accept a camera. It was a long process, but he agreed to it and gave me total freedom. I needed him to make this film, as much as he needed me to make it. To have a trace of it, or to explain what he was trying to do. So I was able to film some amazing things. We travelled 40,000km in Algeria, went to meetings everywhere. I’m wondering how he manages to have three to four meetings a day! I was very tired myself. I could get to a man who was truly alone. The film is called Le Grand Jeu because the population doesn’t exist in this kind of democratic process. It’s just a stop on the way to please those who are powerful and their chancellery. We know that this kind of opponent is in total solitude. He knew perfectly well that he was being used.

He was also being gradually abandoned.

He was, especially at the end. At first he was very strong, and then, you can feel him slip into solitude. That’s why I blur the images, even though they were clear. It’s done in post. I zoom in on my own images, because I feel that there is no respect for the population. It’s just double-talk, when we all know that Bouteflika will stay. It’s all made up. It’s a game authorised by the powerful, who know the game is rigged and yet send observants to validate the election. Hence this desire for me to almost tarnish this image of these people because in the end we sully them. No one is looking at them in the end, they almost don’t exist, a ghost population. It’s nothing but a show.

He was, especially at the end. At first he was very strong, and then, you can feel him slip into solitude. That’s why I blur the images, even though they were clear. It’s done in post. I zoom in on my own images, because I feel that there is no respect for the population. It’s just double-talk, when we all know that Bouteflika will stay. It’s all made up. It’s a game authorised by the powerful, who know the game is rigged and yet send observants to validate the election. Hence this desire for me to almost tarnish this image of these people because in the end we sully them. No one is looking at them in the end, they almost don’t exist, a ghost population. It’s nothing but a show.

You work on your image a few times to express an opinion.

Absolutely.

Now let’s watch an excerpt from La Chine est encore loin. The title comes from a Hadith by the prophet that says “Seek for knowledge even if you have to go to China.” Knowledge is what school teaches us, in Tifelfel, the place where the Toussaint Rouge happened, and started the riots of ‘54. You’re meeting with people who witnessed these times as a way to fix the question of myth, and how the teacher approaches these questions with his students. You show cutaway shots of students yawning, and then the camera pans to the sky, “shall we move on?”. You’re showing how lively these students can be once they’re out of class and start living, but here, they are stuck in class, with these testimonies and references to the past, when they don’t know what to do with it.

There’s another dimension to it, and maybe you didn’t get it: language. We are in a Berber area, Shawiya, and they are being taught a “standard” Arabic, that they are having trouble with. They probably have family tales about revolution that they would like to share, but they can’t express themselves in standard Arabic. The teacher won’t allow them to tell them in their own language. This history is, once again, locked up between the four walls of a classroom, as they would in a museum. One of the kids says “mosque” instead of “jail” because it has almost the same root. Another kid confuses terrorists from the years of lead with the moudjahidines! That global confusion comes from the fact that almost nothing is explained to them. They also confuse the date of the beginning of the war and the date of the independance. It doesn’t interest them, because they are not being taught true history. And I’ll say it’s dangerous because some of them will become executives, but they still will be blinded by an obscure ideology, and they’ll have no idea about the stakes of this war.

The subject of language is also about the stonewalling we mentioned earlier. It’s a global system.

Yes, we can see Benflis giving orders in standard Arabic, with a deeper voice than the one he uses in the car. Standard Arabic is scary, it’s a mark of authority. You can feel it even with the Arabic language teacher, if you talk with him outside of the school, he uses a very soft Algerian Arabic, there’s nothing hard about it. It is related to the foundation of the Algerian society, as soon as ‘62 with the idea of Pan Arabism. “We are Arabs, we are Arabs and our language is Arabic.” This standardization left us close minded on every level.

Yes, we can see Benflis giving orders in standard Arabic, with a deeper voice than the one he uses in the car. Standard Arabic is scary, it’s a mark of authority. You can feel it even with the Arabic language teacher, if you talk with him outside of the school, he uses a very soft Algerian Arabic, there’s nothing hard about it. It is related to the foundation of the Algerian society, as soon as ‘62 with the idea of Pan Arabism. “We are Arabs, we are Arabs and our language is Arabic.” This standardization left us close minded on every level.

And nothing has changed yet.

Yes, in schools, nothing is changing. If you watch La Chine est encore loin again, it should be alarming. It is something that Algeria should focus on.

Let’s watch a final excerpt, also from La Chine est encore loin, this time it’s about a woman who isn’t shown on screen but whose voice you can hear off-screen: Rachida, the school cleaning lady. [Excerpt] Did she not want to be on screen? You’re filming her through the physicality of her work.

Actually she was the one who gave a structure to the whole film. We shot for a year, four seasons. I explained my process to everyone, from the janitor to Rachida. She refused to be in the film right from the start. Then I asked if I could film her work. She had no problem with it, as long as I didn’t film her body. And as the seasons went on, she let me film her back, then her profile, but never her face, and she never spoke. At the end of the school year, after seeing that everybody else had told me their story, she called me on the phone to say that she was going to tell me about her life. But she didn’t want me to film her. I suggested an audio recording. It allowed me to finish each season with her, for the whole film. She’s the one who gave me the idea for the final editing, with her body, sure, but also with the water, the rags, the buckets, and with bits of her testimony. She talked for two hours, and it was even more violent that what you can hear in the film, it’s almost a summary of the place of the woman in the Algerian and Berber society. If you listen to them, people will give you the most amazing ideas.

Actually she was the one who gave a structure to the whole film. We shot for a year, four seasons. I explained my process to everyone, from the janitor to Rachida. She refused to be in the film right from the start. Then I asked if I could film her work. She had no problem with it, as long as I didn’t film her body. And as the seasons went on, she let me film her back, then her profile, but never her face, and she never spoke. At the end of the school year, after seeing that everybody else had told me their story, she called me on the phone to say that she was going to tell me about her life. But she didn’t want me to film her. I suggested an audio recording. It allowed me to finish each season with her, for the whole film. She’s the one who gave me the idea for the final editing, with her body, sure, but also with the water, the rags, the buckets, and with bits of her testimony. She talked for two hours, and it was even more violent that what you can hear in the film, it’s almost a summary of the place of the woman in the Algerian and Berber society. If you listen to them, people will give you the most amazing ideas.

It’s striking how people understand cinema.

Yes, which is why it’s very important not to fall for the caricature. Things are a lot more complex. There are women here who are way stronger than some Western women, who they say are more free.

Questions from the audience

I understand that each film, each theme dictates its device in a way. At what stage do you decide on the device? The writing stage or in a back and forth between writing and location scouting, or during the shooting?

Between writing and location scouting of course. I start from the principle that the chosen subject must influence the filmic device and the way of telling the story. We must not repeat ourselves in a quasi-habitual form that would put the viewer to sleep. In Wiseman’s films, the mechanisms are always the same. It’s passionate, but it’s all Wiseman. I put myself in danger with a new subject: how will I treat it? On the side of the caregiver or the cared for? Of teachers or of children?

There is really an ethic in your work, this great respect for the people you film, so that they bring a richness to your work and at the same time you also bring them something essential.

This is what I call this collective work that I try to do with people. Once again, I don’t make films about people, but with them. Fiction is a heavy operation where the actors are rehearsed, we have scenes, you have to go fast, it’s a budget, etc. Documentary is malleable, we can do this extremely civic-minded work for the people with whom I am supposed to film but also for the institutions that have agreed to let the camera in. I love the people I film, even my enemies. The most important thing is to be in the logic of the person who speaks and to understand his mechanics. The more you understand, the better you’ll be at listening. This is the problem with the political television of the regime. Private television stations are extremely violent. They create a kind of political vacuum, whereas we could have made educational channels, cultural channels.

This is what I call this collective work that I try to do with people. Once again, I don’t make films about people, but with them. Fiction is a heavy operation where the actors are rehearsed, we have scenes, you have to go fast, it’s a budget, etc. Documentary is malleable, we can do this extremely civic-minded work for the people with whom I am supposed to film but also for the institutions that have agreed to let the camera in. I love the people I film, even my enemies. The most important thing is to be in the logic of the person who speaks and to understand his mechanics. The more you understand, the better you’ll be at listening. This is the problem with the political television of the regime. Private television stations are extremely violent. They create a kind of political vacuum, whereas we could have made educational channels, cultural channels.

Translated by Maeva Aka with collaboration of Madelyn Colvin from the text in french published on the Africultures website.