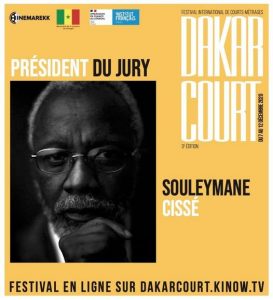

During Dakar Court on December 11th, 2020, Souleymane Cissé sat down with Aboubacar Demba Cissokho and Augustin Diomaye Ngom to answer a few questions, as well as to engage with participants of the training workshop “Talents Dakar Court” 2020.

Augustin Diomaye Ngom : After studying cinema in Moscow, how did you get into directing?

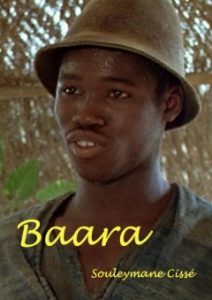

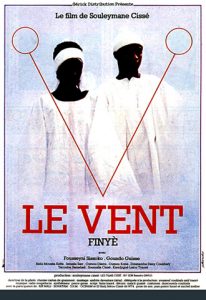

I returned to Mali in November 1969, and in 1970 I worked for the news. After four years, I couldn’t take it anymore. There was a rift between myself and the administration. To exist, I made my first short film, Five Days in a Life which received an award at the International Festival of Carthage in 1972. In 1975, I made my first feature-length film The Young Girlwhich got me arrested and imprisoned for ten days. President Moussa Traoré, to whom I had exposed the problem, got me out. But the film was banned for three years. The actors and technicians got together and decided to make another film, it was the only way to respond to these crooks. We fought, and we were able to make Baara (Work), which won a lot of respect at festivals, and opened the door for me. I then wrote Finye (The Wind) about two young people who love each other, but come from different backgrounds.

I returned to Mali in November 1969, and in 1970 I worked for the news. After four years, I couldn’t take it anymore. There was a rift between myself and the administration. To exist, I made my first short film, Five Days in a Life which received an award at the International Festival of Carthage in 1972. In 1975, I made my first feature-length film The Young Girlwhich got me arrested and imprisoned for ten days. President Moussa Traoré, to whom I had exposed the problem, got me out. But the film was banned for three years. The actors and technicians got together and decided to make another film, it was the only way to respond to these crooks. We fought, and we were able to make Baara (Work), which won a lot of respect at festivals, and opened the door for me. I then wrote Finye (The Wind) about two young people who love each other, but come from different backgrounds.

Aboubacar Demba Cissokho: And you yourself, what state of mind were you in when you were the age of your protagonists?

At that age, I was very much a cinephile. I’ve had a love of the cinema since I was seven years old. There wasn’t a single night in Bamako when I didn’t go to see a film with my brothers. It was a curiosity, each film attracted me, said something to me, even if I didn’t understand the language. It was a golden profession. I was not a militant, but the Independence came and it was greatly discussed amongst my generation. I was a projectionist, and we held debates after the films. In 1961, I was lucky enough to have a scholarship to go to school.

A documentary on the death of Lumumba played a large role…

Yes, it was the news that we were projecting among young people, that friendly countries were sending us. We came across the arrest of Patrice Lumumba. It triggered something in me. I was in tears. When they shoved white paper into Patrice’s mouth, I screamed like a child. It was a shock. It all started from there. Sometimes, films give us a shock that marks us for the rest of our lives.

I decided to go into this trade. I didn’t have a strong intellectual base and I didn’t have my baccalaureate. My childhood was spent at the market, I was a carrier for women who came to buy their vegetables. This allowed me to go to the cinema in the evenings. It shaped me. One day a woman accused me of having stolen her wallet. The police arrested me. They hung me by my feet, my hands were tied together, and they beat me with rulers. Seeing as I was only a kid, I screamed and screamed, “I didn’t take it!” It was the truth: I had not taken it. After three days, I was released. It was a bit tragic, but it makes a man! This woman came to apologize, and I continued to be the little carrier.

Sembène had been expelled from school and also did small side jobs. [He] had been a laborer, then a docker in France before studying cinema in the same school as you in Moscow. Is this why your work in film carries a social, political, and cultural commitment?

I don’t know. It’s up to you to tell me what my cinema is. What you call a commitment, that was an awareness. I was twenty years old, and that changed my life. Each film is a commitment, it’s necessarily that we are all committed, but at the same time everyone is free. The population must be able to take advantage of this freedom.

Moscow: What was the atmosphere like? What vision of cinema was conveyed?

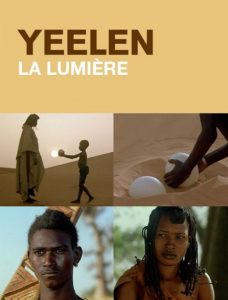

To each their own. I admit that I went to learn the technique of the cinema. The masters who trained me never instilled a system in me. We do not escape the influences [of these systems], but I mostly learned how to make films. Our professors were committed: if we had not understood something during class, they came to our residence hall to continue. I greatly admired that. I was then told that Work or The Wind were socialist, but when Brightness arrived, I was left alone!

To each their own. I admit that I went to learn the technique of the cinema. The masters who trained me never instilled a system in me. We do not escape the influences [of these systems], but I mostly learned how to make films. Our professors were committed: if we had not understood something during class, they came to our residence hall to continue. I greatly admired that. I was then told that Work or The Wind were socialist, but when Brightness arrived, I was left alone!

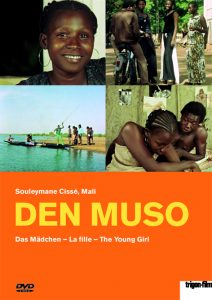

Den Muso: A young girl was raped. We’re going to watch this excerpt.

(the rape scene is emblematic of the quality of Cissé’s cinema: it does not show the act but rather the violence with which the man constrains the women, his hands clasping her arms)

(the rape scene is emblematic of the quality of Cissé’s cinema: it does not show the act but rather the violence with which the man constrains the women, his hands clasping her arms)

What brought you to make this film?

In Mali between 1970 and ‘73, young girls between the ages of 13 and 14 were often pregnant. It was like a trend. This was painful because these young mothers didn’t know where to go. They were rejected by their families and by society. I experienced it in my family, and I could not bear this injustice towards children who become victims of such traps. This is what pushed me to write the scenario. The method was simple. We would shoot in 16mm, would send the film to Paris where it was to be developed and we would wait for the dailies, sometimes for two or three months. The filming stopped while waiting… One time, everything was black, for 30 minutes of dailies! The disappointment was so great that everyone cried. We did the filming again and sent it back: we wanted to make this film but we weren’t professionals. The young technicians had done small internships…

Augustin Diomaye Ngom: It’s striking to see that you show the youth of that time very close, without problems in regard to gender or the body and nudity. Why have we arrived at such a level of censorship today?

Your question is very relevant. When I made my films, I never cared about censorship. The question for me was how to go about doing it. In The Wind, two young people shower together. The nudity is a value, an aesthetic. It is necessary to know how to appreciate it, without vulgarity. Otherwise, we are not helping women or society. It is vulgarity that is revolting. On the other hand, religious censorship is beginning to have an impact. I have film that have been censored for national television. Not to mention the religious television channels, themselves. We must not give up. Everything passes. Everything has its time. We are evolving. We are not going to retreat!

Your question is very relevant. When I made my films, I never cared about censorship. The question for me was how to go about doing it. In The Wind, two young people shower together. The nudity is a value, an aesthetic. It is necessary to know how to appreciate it, without vulgarity. Otherwise, we are not helping women or society. It is vulgarity that is revolting. On the other hand, religious censorship is beginning to have an impact. I have film that have been censored for national television. Not to mention the religious television channels, themselves. We must not give up. Everything passes. Everything has its time. We are evolving. We are not going to retreat!

Aboubaar Demba Cissokho: It’s all in the manner of filming. What you say about Mali is true of Senegal too, even for a kiss in a television series! The debates on Sembène’s Ceddo (1976) remain heated in universities!

(excerpt from The Wind) What makes you smile in seeing these images again?

These are natural acts. The same movements. This film dates from 1980. In 2020, I don’t see the change in Mali!

Augustin Diomaye Ngom: Here’s, it’s the opposite. A lot of things have changed. When we study the audiovisual landscape, everything is extremely focused on a standard of living, on luxury. The landmarks of life are no longer the same, the same is true of the dynamics in couples. Would there not be something universal in values when we hear people say: “These are not our values?” Young people are between a rock and a hard place, between what they want to do and what they are being forced to do.

This generation should see The Wind. In watching it today, I see it as a sort of provocation, but when I made it, everything was natural. It corresponded to reality. I tried to modernize it a little: Students, that’s the future! There’s even a scene with ping-pong, even though it was new at the time! This film poses the problem of young people today.

Aboubacar Demba Cissokho: You’ve received the Stallion of Yennenga two times: what was that experience like for you?

Awards are a compliment. I never would have thought that a film like Five Days in a Life could receive an award. I was in shock. Awards? Bravo, but that’s not the engine. You have to make the film you want to make, listening only to yourself.

Binta Diallo (training workshop Talents Dakar Court): Why not write about female genital mutilation, considering that it’s practiced enormously in Mali?

I believe that this role comes to you because no one can feel it the way that you do. I’m not for it, but I haven’t had the occasion. If you have a good scenario on the subject, we will find someone who will do it better than me.

Augustin Diomaye Ngom: This intersects with the question of the legitimacy of talking about a subject. For example, it becomes problematic to see a White man talking about racism, a man talking about the conditions of women, an abled-person talking about disability, etc.

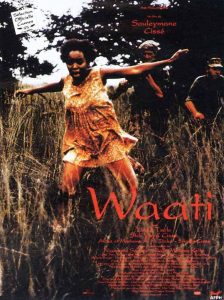

This is not the business of specialists. Anyone can deal with female genital mutilation, even if it is not done where they come from. Waati talks about the racism of the apartheid in South Africa. It was censored there, but we are going to restore it and release it again. As soon as a film does not correspond with the dominant vision, it is blocked.

This is not the business of specialists. Anyone can deal with female genital mutilation, even if it is not done where they come from. Waati talks about the racism of the apartheid in South Africa. It was censored there, but we are going to restore it and release it again. As soon as a film does not correspond with the dominant vision, it is blocked.

Augustin Diomaye Ngom: We still have this problem of a caste system in Senegal, where children abandon the man or woman that they love because their parents decide that the person’s social class is not suitable.

It is our role as filmmakers to say that this is not fair. We don’t need to be aggressive, simply get the public to buy into what we’re saying. It’s a matter of the cinema. On crucial issues, you have to get people to see what they haven’t seen. There’s no shortage of topics! Go for it!

Question from the audience: we live in a world dominated by money. How are we to protect ourselves?

It is difficult for us to make films without having to go through the capitalist system… Each artist takes a different path. Good art sells well, too. The important thing is to express oneself. Nature always gives you the means to succeed if you like what you do and if you do it well. We started Brightness but I didn’t like the results, so I stopped! After a month and a half of shooting. It cost what it cost, but I knew that it would have failed.

It is difficult for us to make films without having to go through the capitalist system… Each artist takes a different path. Good art sells well, too. The important thing is to express oneself. Nature always gives you the means to succeed if you like what you do and if you do it well. We started Brightness but I didn’t like the results, so I stopped! After a month and a half of shooting. It cost what it cost, but I knew that it would have failed.

Toumani Sangaré, producer-director: in the excerpt from The Young Girl we see a dugout canoe passing on the river while the action continues. Do you master everything we see in the image? Is this dugout staged or the result of a coincidence? Do you direct the actors during the shots by instinct or is everything planned beforehand?

The movies that I made up until Brightness, it was with amateurs, except for rare exceptions. I worked with the actors before the shooting. I gave them my instruction and left them the freedom to play, which allowed them to give this weight to the film. As for the dugout, it passed from behind: we didn’t pay for it to come, but we knew that dugouts passed in that area. At one point, we waited an hour before we saw one coming! At the market, I was scared for the boy because I feared that the whole market would turned against him! But you have to take advantage of the gifts of reality!

(translated by Madelyn Colvin from the french published on Africultures)