During the Carthage Film Days 2018, the famous Tunisian film music composer Amine Bouhafa answered questions from the festival’s Director of Communication, Hisham Ben Khamsa. A full transcript of the interview is available below. The film excerpts are to be found on the video of the meeting (timecodes indicated), which is a summary and therefore includes only certain passages of the exchanges and films:

The film professionals acknowledge you as one of their peers and a great composer of film music. Many film and music school students are present in the room. Thank you Amine.

Welcome to all of you. I am very moved to share my passion for film and music. We are going to have a good time together.

Amine, you fell very quickly and very young – like in comic books, in the pot (laughs) – into music, thanks to your mother.

Yes, the pot was big and my mother used to make artistic magic potion in it (laughs). I started playing the piano at the age of three and went to music school at the age of five. I finished the music school at twelve. I only studied there for six years because I skipped a year. At that time, people had to study 7 years to get the diploma. I wanted to finish the music school so I could take up the piano seriously.

And at the same time, you were good at school. You studied mathematics in a higher school preparatory class after high school graduation.

And at the same time, you were good at school. You studied mathematics in a higher school preparatory class after high school graduation.

That was the sine qua non condition to go to Paris and try to branch off into an artistic career. Then I went to a telecommunications engineering school.

And you were hired by France Telecom.

At another consulting firm. But music was always in my heart. I was waiting for the moment when I could live from my passion. I also went to the Paris Conservatory. I dreamed of studying orchestration, analysis, writing, harmony, jazz arrangement and acoustics. It was a very complete, very erudite and magnificent training.

You didn’t wait for your math studies to compose film music.

Indeed, I composed my first film music when I was 15 years old. I was very young.

The first time you came to Carthage was for the short film Les Poupées de Sucre, by Anis Lassoued.

That’s right. When I was 15. I saw Anis yesterday and he asked me, « how old were you? » and I said, « I was 15. » That’s when my passion for cinema was born. Actually, that passion was born through film music. I remember that the music of the film Schindler’s List touched me a lot. Little by little, I began to take an interest in the great Hollywood symphonists of the 50’s and 60’s. That’s how I became interested in cinema. I used to go to movies to listen to their music. Now I go to movies to listen to their musicality.

Everyone knows Amine Bouhafa and the César for Timbuktu. And yet, this is not your first project.

Yes. From memory, this is my 9th project. I was very lucky to be called in to work on this project because Abderrahmane Sissako is one of the greatest directors of our time. It’s a dream that has lasted for more than two years. From the 2014 Cannes Film Festival to the Oscars.

And above all, everyone is talking about the Césars, but the real big prize that music fans are most proud of is the France Musique award.

I’m very proud and happy to have received this award.

How’s the festival going for you?

What’s wonderful is to be able to meet people who are passionate about cinema, to exchange and discuss with them. It’s true that seeing my films screened in international festivals makes me happy. But when I start working on a film, I never do it with festivals in mind. The most important thing is to be able to carry the film in the best possible way, to meet people and exchange this common passion.

We talk about Timbuktu but your defining characteristic is to be recognized in the Arab world.

I’m very proud of that because when you’re recognized in your own world, it’s heart-warming. I’m very happy to be able to juggle with two parallel careers: in the Arab world, especially in Egypt with series, but also internationally.

I’m very proud of that because when you’re recognized in your own world, it’s heart-warming. I’m very happy to be able to juggle with two parallel careers: in the Arab world, especially in Egypt with series, but also internationally.

And lately on Netflix.

Indeed, with the first Arab series broadcast on Netflix: Secret of the Nile composed of 30 episodes.

What are you going to cook for us today?

It’s an opportunity to share my passion for music and cinema, to talk about the things I love, including the power of music, its third dimension for a film, the fact that it can bring out what you don’t see on the screen, its function, and the choice of when it comes into play. The relationship between music and colours, as well as light are also important. It reminds me of a quote from Cocteau « Cinema is modern writing, where ink is light ». If anything inspires me in cinema, it’s the colours and the light. So, I would like to share with you these reflections around colours and light: how to interpret a light or be inspired by it in a musical format? I think it’s good to start with a video presentation to get us started.

(Broadcast of the end of Beauty and the Dogs by Kaouther Ben Hania, beginning at 11:08)

Here I wanted to show you the evocative role of music, which brings hope and light. The role of music would be the narration and emotion as here, the theme as in Timbuktu, and a third would be a suggestive role where the music would suggest another image.

Are these singles interchangeable?

Absolutely. We should start with the beginning of the films. The beginning is a crucial moment for any artistic work, be it a play or music. That’s when the setting and the mood of the film are set: we take the spectator into the universe of the film. The music brings an element that the director chooses not to put on screen. It brings another reading grid, a certain depth. It can be a past or future drama, the psychology or background of the character, a trauma, something unsaid, etc. The composer will write and complete the cinematic puzzle.

Can a composer bring or impose an idea that the director hadn’t seen?

No, the composer can’t impose anything (laughs). The film is a collective work. Being a composer is a lesson in humility towards group work. We serve the director’s purpose. The most important thing is the film. You have to put your composer’s ego aside. Usually, we intervene at the end. In a way, the director entrusts his baby to us. It’s a relationship of listening and trust. Listening to the director is one of the characteristics of the profession. You have to have a strength of analysis and synthesis in order to propose the music that the film needs. I try to retrieve and analyse the maximum amount of information that the director brings and I convey the sound that he imagines.

It would be interesting to have the director’s point of view once he has heard the music, and to know if it meets his expectations and if he can discover an element that was visibly hidden.

It would be interesting to have the director’s point of view once he has heard the music, and to know if it meets his expectations and if he can discover an element that was visibly hidden.

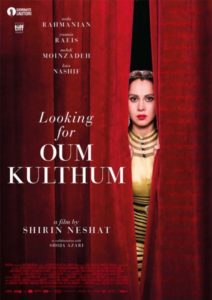

I’ll show you two examples. Today, more and more, for technical reasons, existing music is used to edit a film. I had the chance to work with one of the emblematic artists of contemporary cinema: Shirin Neshat (Iranian director based in New York), who has a very personal and strong visual aesthetic. To edit the beginning of her film, she used existing music that I had composed on another project. So I’d like to present the two versions of the beginning of the film, first with the music used to edit the film, and then with the music I had composed for the film.

(Amine first broadcasts the beginning of the film Looking for Oum Kulthum with the first music. You can hear a sweet melody without words, with piano and violin tunes. Suddenly he comments: « the picture is very beautiful ». This excerpt lasts about three minutes. Then he plays the same excerpt with the second music, which has a different, but also soft melody. There are violin tunes, and heels clicking against the ground. He comments: « we see childhood memories, a little girl »)

In the first excerpt, at the beginning, the music says exactly what we see on the screen. It’s very narrative. We see a period image, very romantic music by the orchestra, lyrical. In the second extract, the music adds a mysterious universe, a little magic, an element that you don’t see on screen. The music accompanies the steps. In the first excerpt, we see the romance, whereas in the second excerpt, we have a discourse that is distant from what we see, and it also announces the mystery that will arise during the film. Typically, the first music is narrative. It’s storytelling. It’s as if the director uses another voice to tell his story. The music can also be functional, evocative of emotion, suggestive of images (which applies to genres such as science fiction or action) or fictional (which writes a speech, brings a universe and a sound identity). This is not a judgment of value, it is only a decision of the director. Narrative music is associated with the notion of theme. I’m thinking of Timbuktu‘s music, which has a theme.

(Amine plays the Timbuktu theme on the piano before playing the first images of the film where this theme is taken up again)

(Amine plays the Timbuktu theme on the piano before playing the first images of the film where this theme is taken up again)

These are very simple harmonies, a very simple theme. This notion of theme tells a story. When you listen to the music alone, you feel this narrative side. In Timbuktu, one of the functions that we wanted to bring to the film music was the narrative function.

(Amine compares two excerpts by first playing an excerpt of about a minute from the film Timbuktu in order to show the narrative function of the music. At the same time, he comments: “We start with a clarinet in the low register of the instrument, with silences.” Later on, other instruments can be heard in addition to the clarinet. Then he plays the same excerpt with a different instrumentation. We hear clarinet tunes, the crying of a child, gunfire, and the sound of an engine. Other instruments are added to this. The second excerpt lasts about two minutes)

Cinema is an art independent of our experience, because we are always beginners. Unlike all the other scenes in the film, I spent a lot of time composing the end scene I just showed you because it didn’t fit. I asked Abderrahmane a lot of questions to understand what was wrong (about instrumentation, rhythm, emotion, etc.), but I didn’t have a precise answer. He had quoted Dostoyevsky to me: « No science is worth a child’s tears, » and I had asked him about the relationship between a child’s tears and this scene. I slept with this confused idea and tried to interpret this sentence. Music is not a science, but it could be a form of science. Then I understood that he wanted us to hear that child crying as he ran, because nothing is worth a child’s tears and music should not hide them. I built a music that would gradually fade away, that would go downhill, leaving only the child’s breath. What moved me about working with Abderrahmane was that he let me enter his universe, feeding me with these metaphors and leaving me free to interpret them.

This collaboration at the end of the film corresponds to another dimension than the moment of the writing. During the composition of the music, two or three years after writing the script, there may be elements that the director would not have thought of. Faced with this director, can we relive this experience in order to bring this new dimension?

We really need to bring him added value. But the earlier we intervene, the more likely we are to make a mistake. At each stage of the filmmaking process (writing, shooting, editing), the film changes face. Working on the image inspires me the most (the light, the colours, the rhythm). But I have written on screenplay several times, and that gives me more time. You then give yourself the means to make mistakes.

What’s the difference between working several times with the same director and working for the first time? Do you rediscover each other?

What’s the difference between working several times with the same director and working for the first time? Do you rediscover each other?

As I was saying, no matter how many years of experience you have, you’re still a beginner. So if one comes up with a pretentious idea of what one wants to do, one won’t surprise their self and there won’t be any challenge. You have to be in constant denial about what you’ve done. It’s like in a romantic relationship. Routine breaks everything. You always have to create something new, surprise yourself, look for a new language, a new writing process. I’m always trying to change my way of thinking. For Timbuktu, I wrote a theme and then I changed it. In Beauty and the Dogs, Kaouther wanted a music that you could listen to but not hear. I thought it was interesting and I wondered how I could get away from it all. In the writing process, instead of composing directly on the picture, I watched the film six or seven times and then I left it out. And I used the memories and impressions that the film had given me. I created a kind of sound palette and explored instruments that I’m not used to using. I really based myself on the creation of a palette rather than on the theme. I used a Cristal Baschet (an instrument from the 70’s) which is featured with a duality of crystalline and dark sounds, and bows to create musical tension. I’m talking about the technical aspect to show you that there is not only one way to compose. It was really a sound laboratory. I sent Kaouther seven or eight pieces of music. Then I went back to the film scene by scene using that palette.

Beauty and the Dogs won the award for Best Sound Creation at the Cannes Film Festival.

It’s a well thought-out award that celebrates a collaboration. It reminds me of a sequence from Beauty and the Dogs: we’re in a dark musical register until it gets very bright and hopeful at the end. Here, the music creates an extra emotion of liberation. And this, at the same time as the heroine puts on her veil and instead of hiding with it, she puts it on like a superhero’s cape.

(Broadcast of an excerpt from the film Beauty and the Dogs. First, we hear an argument between men, then the music comes in, and we can hear heels clicking on the ground. This excerpt lasts more than a minute)

I wanted to show you the evocative role of the music, which brings hope and light. I showed you two music functions through Timbuktu and Beauty and the Dogs: narration (the theme) and emotion. Now, I will show you the suggestive role of another image with an excerpt from Looking for Oum Kulthum. To explain the context, the heroine has a tense relationship with her son, whom she hasn’t seen for a long time. But she still has visions. There’s a surrealist side to the director.

(Excerpt begins at 13:58 – Broadcast of the excerpt with music, explained just before. It lasts about two minutes)

It’s an example of music that could support this surrealist, dreamy side. It could have a fictional role. Sometimes the director really wants the spectator to take a side, and fully live what the character is experiencing. And at other times, the director would like the spectator to be a simple observer and take a certain distance from what they see. The music could play this fictional role of either taking the spectator inside the scene or letting them step back. For a scene from Beauty and the Dogs, I suggested two kinds of music to Kaouther: one is visceral, where we follow the heroine inside the scene, and the other is rather distant and keeps the spectator in observation in relation to what the heroine is going through. I’ll show you both versions and you can tell me what you think. Without spoiling the film for you, this is the moment when the heroine has for the first time a tangible proof of her assault by police officers: her phone is in their car.

(Extract begins at 20:00 – Broadcast of the musical extracts explained just before. We hear the heroine’s screams who finds the phone, as well as the movement around her, with a little music. He comments on the first excerpt: “we hear the ringing,” then “the tension rises with her race.” This lasts more than a minute. Then he plays the second excerpt. First, we hear the heroine’s screams, then only the music. He then asks the opinion of the audience, who mostly prefer the first extract)

The first extract wins, the director was right (laughs). The first extract was visceral, organic. You experience what the heroine is going through. You experience her anguish. That’s her point of view. Whereas in the other extract, the point of view is external, and the spectator watches her living her nightmare. When music could play a fictional role, these are two different examples. There can be a contrast between functional music and fictional music. In the Timbuktu football scene, which is an example where music plays a balanced role between the functional and the fictional, the music accompanies the image and holds a dramatic discourse. This scene is mythical and is the work of a directing genius. The first time I saw it, I didn’t realise there was no ball!

For people who have not seen the film, it tells the story of a group of extreme Islamic jihadists invading a village and banning music and sports. So we see young boys playing football without a ball.

For people who have not seen the film, it tells the story of a group of extreme Islamic jihadists invading a village and banning music and sports. So we see young boys playing football without a ball.

We don’t see a football match, we see a ballet, a dance.

(Excerpt from Timbuktu, a scene from the football match without a ball, 26:50 – turns black on the screen. We see the group of jihadists forbidding the ball to young people. Then a cheerful music comes at the end of the line. Amine Bouhafa comments: « We hear small drops of celesta and triangles representing the character of the ball. The excerpt lasts about two minutes).

When is music placed in one place and not the other?

In the jargon of film music composers, this is called ‘spotting’. It is one of the most important working sessions where you decide when the music is going to come in and when it is going to go out. I like it when you don’t notice when the music comes in, when it’s there, but you don’t feel it. If you can feel it, it’s a bad exercise. It can be brought on by a noise: a passing car, a door slamming, a scream. When the music is there, it’s hard to get rid of this feeling of presence. We must also think about silence, as Jeanson said, « Sound cinema made us discover silence ». Among other things, silence makes us appreciate music. We have to find the right balance between silence and music. Like when you make coffee, if you put too much coffee in it, it’s not good (laughs). I think this talk is very important. It’s a choice between the director and the composer because the director already has a clear idea of the location and the composer can surprise him with their ideas. The location of the music can also come from the function. Once you have decided on its narrative, evocative or fictional function, it can help you find elements to reflect on. You’ll make a music that is specific to a character, that will accompany his fall into hell or his journey, and in each situation, you will be able to reuse the same music. Within the same scene, the location of the music can bring a different look or function. I’m thinking in particular of a scene in the second plan of a sequence from Beauty and the Dogs, where we tried different locations, which brought different functions.

(Excerpts begins at 35:20 – Amine shows that scene and comments: « We’re about 12 minutes into the film, the scene represents a complete break because we were in a happy atmosphere. The music starts at the beginning of the scene. The trumpet represents the character’s voice. It accompanies the percussions. There is a bit of piano at the entrance of the character in the hospital. The music ends before the dialogue. The music comments on the images.” Then he shows a second possibility of music location, and comments: « No more music at the beginning, only silence and the scream of the character. The music is added after the sound of the car. The crystal baschet accompanies the percussion. The trumpet no longer represents the character. The music slowly disappears.” Finally, he shows a third possibility with the music at the end of the scene. He comments: « The music starts at the entrance of the hospital. We can sense that a drama is about to happen, as if to warn the spectator.”)

What would you have chosen? I see that the majority chose the music set at the end of the stage. We kept the music in the middle because we’re not in the drama announced at the end. It gave a sound atmosphere and it completed what we were seeing. There’s no narrative function.

We just saw the race, the steps, the entrance… Did you think it could create a break with the previous scene and create a new atmosphere announcing drama?

Yes, I did. In the previous scene, people are dancing in a nightclub, it seems that there is going to be a dispute. And all of a sudden, they are running, the man behind her, so you think something happened between them. Then you realize he’s helping her. And you really wonder what’s going on, and you’re confused. The music in the middle announces something unsaid, a drama that happened before and that we didn’t see, that the director chose to hide. It’s the music that brings that drama.

We’re talking about an original composition, but with Looking for Oum Kulthum, we expect to see Umm Kulthum’s repertoire. How do you balance things so that the music is original? In the film, there are excerpts from her songs, we’re in a kind of complex hybrid. Were you able to not think about her music?

When I was called in for this project, I was scared. I’ve been living with Umm Kulthum’s voice since I was very young, so I had a big responsibility in taking on the greatest Arab diva. It’s a big challenge. It’s not a film about Umm Kulthum, it’s an abyss. We’re talking about a director who wants to make a film about Umm Kulthum. We had Shirin Neshat’s particular aesthetic universe and the temporal contrast of a very contemporary universe, brought by some of Umm Kulthum’s songs. From the start, the common choice with Shirin was to create a contrast between the music written for the film and the classical repertoire of Umm Kulthum.

Who chose the songs?

We worked intensely two months before the filming on the choice of songs, on the evolution of her voice, her pronunciation. The evolution of the musical character was very deepen. It was very important for me to keep the authenticity of Umm Kulthum without adding any arrangements. To do that, I worked on the twenties, like an historian. I went to Cairo and we recorded in the studios where Umm Kulthum recorded. The musicians had to play in exactly the same way as she did. And I insisted on using the same microphones she used. I played with musicians who’d already played with her on her last concerts, as well as their sons. During the recording, I closed my eyes and was moved. I had the feeling that she was going to come and sing, thanks to the wooded side of the studio, the old microphones and the way the musicians were spread out on stage. I reproduced the same scenography, with the microphone in front of them. The score was very minimalist, uncluttered and contemporary with a modern and acoustic writing.

Umm Kulthum’s sound evolves, due to the technology of the time. What is the importance and the difference of the relationship between music and sound?

The music is part of the ‘soundtrack energy’ of the film. You can’t think music if you don’t listen to the film. You can’t ignore the sound. It happens very often that I remove the images and only listen to the sound, the dialogues. It’s a very important relationship. Being a composer of film music is a big lesson in humility and respect. It’s a collective work. In my previous collaborations, I wanted to send the demos to the sound editor and mixer so that they could include them in their work. And vice versa, I also wanted to see what they did with them. For example, if a truck passes by in the film, you can’t add a double bass to the sound spectrum of the music. It’s a collaboration, a mutual respect for the sake of the film. If you want to make a career as a composer, you have to make basic music. To be a composer of film music, you have to think about cinema. Then, if you can listen to the music alone after you’ve seen the film, that’s a bonus.

What’s a bonus?

The film is a bonus. Film music is made to support a film, but if you can listen to it alone, it’s a bonus.

Could you compose silent film music?

Of course, it’s a challenge. I’m very open-minded, I like all films. Coming back to this question of sound and music, I can show you two excerpts where the music cohabits with the sound. One is from Beauty and the Dogs, where the sound disappears to make way for the music. So that produces a sound bubble that accompanies the scene. Then the music disappears to give birth to the sound again. And the other excerpt is from Looking for Oum Kulthum, where a diegetic music (the music that the characters listen to) disappears to give birth to a score. It’s a kind of bubble. Nowadays, one goes to the cinema more to extract oneself from reality than to watch it. Music can contribute to this veracity of reality.

(From Beauty and the Dogs (59:42)) – You can hear soft music. He comments: « Music replaces what we see on screen. We don’t see the characters talking but we see the heat rising between them. The carnal side accelerates. You know something is going to happen. The music comes down little by little to give birth to the sound of the film.” Then, excerpt in 1:01:10 of Looking for Oum Kulthum. He comments: “There’s a party, with chill music. We see the surrealist universe of the director through the character’s visions. The music starts to come out and creates a sound bubble. Then the sound resumes.”)

I wanted to emphasize the importance of working with sound and thinking about music in a sound collective.

You talked about collective. To record film music, you go to several cities in Europe. You’ve also been a conductor for galas. When you’ve seen the film and you conduct a symphony orchestra, how do you involve the people present in the studio when they haven’t seen the film?

Music is an exact science. When you write a score, there’s an attention to detail. The manner of interpretation is written in the score. All the intentions of playing are there. I still want the film to be seen on the screen. When I play, I have the film in front of me. Even if everything is written down, the musicians will always bring a human side to the interpretation. And since we’ve already worked with a director and validated the demos, this human side can take the music into a new register. We’re always in the approximation, so it’s important to see the film while it’s being recorded. For example, in the film Gun Shot I recently recorded, I had a French horn solo (a brass instrument) which reminds me of the United States. But I wanted a sound without any patriotic connotation. One of the musicians put a mute in front of the instrument and we managed to get a squeaky sound perfect for the stage. When you have the luxury of having musicians on stage, it’s wonderful because they’ve got a lot to offer too. But you always have to bear in mind that you’ve already validated a demo with the director and that you have to make music made on the computer as human as possible without altering its purpose.

Kaouther Ben Hania – I’m going to come back to an element that Amine mentioned: when I think of a film, I think of the duality of image and sound. It’s quite precious. We have an immediate relationship to the image, that is to say, we analyse it in a direct and conscious way. Whereas in sound, there is a large unconscious part of sound. When I write a film, I ask myself what the viewer is going to get out of the film. Where should I take them, what information should I give them? The composition should be directed towards the viewer’s unconscious. They follow events through the image, but the feeling of identification with the character comes from the sound. It was interesting to see the scene where the heroine runs away with two versions of music, because the film is a question of perspective. I really wanted viewers to understand the psychology of the character. I always try to discuss with all my fellow-workers to avoid the obvious. If you don’t talk, you don’t explore the possibilities and that’s a shame. We don’t talk about instruments but about emotion and the intentions of the scene. I go back to the script and I wonder why I wrote in such a way. I explained my intentions to Amine, giving him the freedom to interpret them, then he offered me several demos. The music is at the service of the film, it’s linked to the depth it will bring to it. It’s very special. In the long and exhausting process of making the film, we start working with the musician in post-production (often after editing). If the musician is not enthusiastic and doesn’t really want to serve the film, it’s quite complicated, because we’re exhausted. This is true for all post-production departments. Indeed, I observed the relationship between the composer and the musician, as well as the sound editor. It depends on the evolution of the production, but we don’t always have the mock-ups, it also happens that we don’t have the music during the editing. So it’s very complicated juggling.

Kaouther Ben Hania – I’m going to come back to an element that Amine mentioned: when I think of a film, I think of the duality of image and sound. It’s quite precious. We have an immediate relationship to the image, that is to say, we analyse it in a direct and conscious way. Whereas in sound, there is a large unconscious part of sound. When I write a film, I ask myself what the viewer is going to get out of the film. Where should I take them, what information should I give them? The composition should be directed towards the viewer’s unconscious. They follow events through the image, but the feeling of identification with the character comes from the sound. It was interesting to see the scene where the heroine runs away with two versions of music, because the film is a question of perspective. I really wanted viewers to understand the psychology of the character. I always try to discuss with all my fellow-workers to avoid the obvious. If you don’t talk, you don’t explore the possibilities and that’s a shame. We don’t talk about instruments but about emotion and the intentions of the scene. I go back to the script and I wonder why I wrote in such a way. I explained my intentions to Amine, giving him the freedom to interpret them, then he offered me several demos. The music is at the service of the film, it’s linked to the depth it will bring to it. It’s very special. In the long and exhausting process of making the film, we start working with the musician in post-production (often after editing). If the musician is not enthusiastic and doesn’t really want to serve the film, it’s quite complicated, because we’re exhausted. This is true for all post-production departments. Indeed, I observed the relationship between the composer and the musician, as well as the sound editor. It depends on the evolution of the production, but we don’t always have the mock-ups, it also happens that we don’t have the music during the editing. So it’s very complicated juggling.

A master’s student in cinema – Hello Amine. I’m currently writing a master’s research thesis on the music of Timbuktu. In your collaboration with Abderrahmane, between technique and ideology, how do you translate his ideas into music?

As with Kaouther, we didn’t talk about instruments or technique. He nourished my reflection with his intentions as a director, his metaphors, his cinematic discourse: an intention that you feel in the image, a narrative role that he wanted (an element that you don’t see on the screen). I remember a scene where we saw a Nigerian fisherman and I asked him about emotion. And instead of answering my questions, he told me that he hadn’t found an actor. And on the day of shooting, he had shot the scene without an actor. Finally, his assistant had found a real fisherman they filmed. And when I got home, I wondered why he told me about it. He gave me a freedom of interpretation to this situation and I understood that he wanted the truth in this scene. He didn’t want the music to be put on a picture, he wanted it to come out of the picture. That’s how we worked together.

Jean-Marie Mollo Olinga (film critic) – I’d like you to explain to me how you work on staging when the music becomes extra-diegetic and has to become diegetic again, in terms of spotting. I explain it with a specific image. When you watch a western, you can put yourself in the shoes of the rider and the spectator. When the rider come out from far away, you can hear the sound of the horse’s heels coming closer. There’s something bluffing about cinema: it’s the real thing. When you’re in the middle of diegetic music and you have to turn it off, you keep hearing whispers, and that’s a problem for me in terms of staging the sound and the music. Thank you for that.

Kaouther Ben Hania – That’s a bit like what I was explaining, I’m going back to the scene where we decided not to let the dialogue be audible. This film is a bit special because it is shot in sequence shot, so I sometimes find that some of the dialogue is useless. For example, when a girl meets a young man in a nightclub. You can see what they’re going to talk about, and their posture speaks better than their dialogue. To take the banality out of their dialogue and to make you feel the desire that rises between them, we used sound. We go from a realistic nightclub atmosphere to one that suggests a certain intimacy. In terms of the collaboration between a director and a composer, Amine and I have just made my latest short film Sheikh’s Watermelons. It’s a comedy that has nothing to do with Beauty and the Dogs, so we had a lot of fun. We’re in the cartoon, there’s this western side with the sheriff receiving a pie. The music in this film is completely different. With each new project, it’s as if we hadn’t done anything before and started from scratch.

Amine Bouhafa – Indeed, the relationship between sound and music has a fusional side. In film school, students are told to not use solo instruments when there are already characters talking, because you wouldn’t hear the dialogue any more. The musician has to hold back. Or in another case, there are two solo instruments that answer each other with the voices of the girl and the boy. Kaouther used to tell me to put a drop here and there when their mouths opened. We really wanted to draw this intimate relationship that was created with the music. We’d replace what we couldn’t hear with music. You feel you have to think about it with the director.

A music composer and sound engineer – For the film Timbuktu, how difficult was it to combine orchestral music with typically African music which is often very dissonant? What was the challenge to harmonize everything?

The first challenge was to enter the world of African music. I think Abderrahmane Sissako is a big name in African cinema. I went out and listened to all the references. When I saw the film, the first thing that came to my mind was that it would be a mistake to only produce African music for this film (with the kora and the balafon). That would have been to confine the film to a local discourse when it has a universal message. On screen, a crowd is attacked by religious extremists and holds firm, the inhabitants don’t let themselves be attacked, they play football without a ball, sing, love each other and push the boundaries of the forbidden even if they are stoned. There was a kind of resistance. I wanted to push the boundaries with music and be where people don’t expect us to be, by creating universal music with African tunes. I wanted a Béjart-style dance music, with the jihadist making gestures during the stoning sequence. I wanted to do a theme song with Fatoumata Diawara (a Malian singer) using African instruments and the symphony orchestra, making it bluesy. That was very important to me and it motivated our thinking.

(At 1:31:16, Amine closes the masterclass by playing an original piano composition: Grand Hôtel. The audience applauds, and Amine thanks them)

Translated by Sarah Lebeau with collaboration of Madelyn Colvin from the text in french published on the Africultures website.