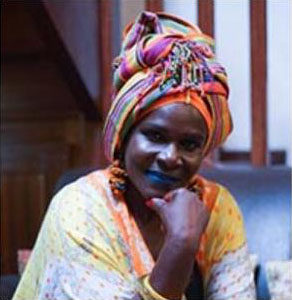

The first « zoom » panel of the Pavillon of African cinemas hosted on June 22nd by the African Cultural Agency at the Cannes 2020 virtual Film Market was moderated by Hortense Assaga (journalist). The panel brought together Nadia Rais (animation director, Tunisia), Maïmouna Ndiaye (actress and director, Senegal), Naky Sy Savané (actress, Côte d’Ivoire), Marie-Clémence Andriamonta-Paes (producer and filmmaker, Madagascar) and Fatou Kiné Sène (critic and journalist, Senegal). You can find the summary of the panel below, and you can find the full panel on Youtube here.

Hortense Assage: In Africa, like everywhere in the world, equality is lacking in the 7th art. Here are women who are keen to share their struggle to make their voices heard and be recognized as professionals in their own rights. What is the situation in Africa? What is the situation on other continents? How do the women who do, do to do well? How do they act on a daily basis? How do they make their presence known? How do they experience their gender? Do they use their gender, or is it just another one of their qualities? Let’s start with Fatou Kiné Sène, who is in Dakar and was elected president of the African Federation of Cinematographic Criticism (AFCC) in March 2019. How do you apprehend the job of film critic?

Hortense Assage: In Africa, like everywhere in the world, equality is lacking in the 7th art. Here are women who are keen to share their struggle to make their voices heard and be recognized as professionals in their own rights. What is the situation in Africa? What is the situation on other continents? How do the women who do, do to do well? How do they act on a daily basis? How do they make their presence known? How do they experience their gender? Do they use their gender, or is it just another one of their qualities? Let’s start with Fatou Kiné Sène, who is in Dakar and was elected president of the African Federation of Cinematographic Criticism (AFCC) in March 2019. How do you apprehend the job of film critic?

Fatou Kiné Sène: It’s not a job that you were taught at school. It comes with passion, with the movies. The appreciation must be based on clear and precise points. Criticism is subjective, but it must be based on solid points. It’s not a question of demeaning a film. Criticism also allows us to give small visibility to the film, to encourage others to go and see the film and to make the work of directors and all the cinema technicians visible.

Hortense Assaga: Is it easy to give an opinion that can sometimes be negative and have the people in question ever been angry at you?

Fatou Kiné Sène: Since I started writing film critics in 2007, people have sometimes been unhappy with what I wrote. They came to see me, we talked about it and in the end, they agreed with the reasoning. It’s important not to bring down a film but to insist on what makes it excellent or what could make it better. But we are not directors: our role is to inform the readers, the viewers.

Fatou Kiné Sène: Since I started writing film critics in 2007, people have sometimes been unhappy with what I wrote. They came to see me, we talked about it and in the end, they agreed with the reasoning. It’s important not to bring down a film but to insist on what makes it excellent or what could make it better. But we are not directors: our role is to inform the readers, the viewers.

Hortense Assaga: Marie-Clémence Anriamonta-Paes, what do you think about what Fatou just said?

Marie-Clémence Andriamonta-Paes: I think it’s really interesting. It’s a pleasure to have with us critics such as Fatou and Olivier Barlet – there are only a few critics with whom we can interact equally. Fatou very rightly said that the way a movie is perceived and criticized is of course subjective. Sometimes you want to reply with an angry letter! It’s better not to read anything about our movies, our babies, when they’re released! With time, you learn to put things in perspective. One day, in Belgium, someone told me that birds don’t care what ornithologists think. That shouldn’t stop you from moving on and keep going, a bad critic is not the end of the world. Bad critics do exist, as well as bad films! For example, some people always say a movie is terrible: that’s not criticism!

Hortense Assaga: Is there a cultural or multicultural comprehension of criticism? In our African habits, when someone criticizes you, you tell yourself that they don’t like you, or that it’s because you’re different… Does culture play a role in criticism?

Marie-Clémence Andriamonta-Paes: Today, criticism is global and that’s the fascinating part of it. In the past, and even fifteen years ago, when our movie was released in France we only cared about French criticisms, and when our movie was released in Madagascar, we looked at what journalists were saying there. Today, movies are released at the same time all over the world. So we can put the critics side by side. It happened to me for Fahavalo, I had side by side a critic from Soleil de Dakar and another one from El Pais in Spain. This leads to seeing the movie globally.

Marie-Clémence Andriamonta-Paes: Today, criticism is global and that’s the fascinating part of it. In the past, and even fifteen years ago, when our movie was released in France we only cared about French criticisms, and when our movie was released in Madagascar, we looked at what journalists were saying there. Today, movies are released at the same time all over the world. So we can put the critics side by side. It happened to me for Fahavalo, I had side by side a critic from Soleil de Dakar and another one from El Pais in Spain. This leads to seeing the movie globally.

Hortense Assaga: How did you manage to find your way in this rather unequal industry?

Marie-Clémence Andriamonta-Paes: I never had the feeling that it was harder for me because I was a woman. I did feel like it was harder for me because I wasn’t French or because I was talking about realities that seem to be less important, as if there was a hierarchy and that European societies were more important than ours. That being said, I have the chance of working with my husband, knowing that the issue of gender inequality is a daily struggle with every man.

Hortense Assaga: When you chose to be a director, a producer, you didn’t ask yourself any particular question about gender?

Marie-Clémence Andriamonta-Paes: It is true that I come from a culture where women’s freedom is like riding a bike: if you don’t pedal, the bike will fall over. It’s a daily struggle. Of course, laws are extremely important to help the most vulnerable people, but that’s an active job. So I feel I have to say every day like I feel I have to say every day »I’m a director from a Southern country and the stories I tell are as important as yours ».

Hortense Assaga: How are you involved today in the struggles and fights led by our sisters for more equality in the industry?

Marie-Clémence Andriamonta-Paes: It’s important because it is indeed an environment where there is a very patriarchal power. There are very few people who decide which films are made and which are not. At least in Europe, few people have the right of life and death on a project, especially for big films with a lot of money. Are these people more likely to be men? I think so, yes. In consequence, women are often in a position of having to deal with this submission. You have to be aware of these women who really are at the mercy of one man, one director or one filmmaker. It’s to help those women that we need to make more noise, to make people aware that it’s not ok, that it’s not natural to obey and to have to serve.

Hortense Assaga: Naky Sy Savané, the most famous « pagneuse » in worldwide cinema, how did you impose yourself and have you seen the place of women evolve?

Naky Sy Savané: We have some very great actresses in Africa who have done an incredible work, but we’ve seen that things were not moving forward. It’s always complicated to make your way in the film industry. Apart from Sembène Ousmane, directors usually give important roles to men!

Hortense Assaga: The book Black is Not My Job had highlighted the challenges faced.

Naky Sy Savané: Yes, it’s the opportunity to salute Aïssa Maïga’s work! I had a career in Africa before coming to the West. I often refused to play overly stereotyped roles. It’s a choice you have to stand for.

Hortense Assaga: Did building a career in Africa make you stronger, more demanding?

Naky Sy Savané: It made me stronger indeed. It gave me the chance to have people write roles for me, whether it is for the screen or the stage. I don’t say yes to every role: I’m free to make my own choices. And that creates an image: the image of an actress is important, it’s her business! Some actresses build themselves up through social media: even if they only did one movie, they’re everywhere! I wanted to build my image as an actress based on my work, and as in my everyday life I’m a feminist activist, I didn’t want my image to be associated with everything.

Hortense Assaga: Mouna Ndiaye, thank you for joining us. Naky told us that making movies is a commitment, a way of fighting. Does that speak to you?

Mouna Ndiaye: That speaks to me a lot, especially since the last time I met with Naky, we talked a lot about our respective commitments. Making films means speaking out to say loud and clear what many people think but don’t dare to say out loud, especially women, children and vulnerable people. Actually, I think we must use this tool to try and carry a message and make things move, make things change so we can move forward together.

Mouna Ndiaye: That speaks to me a lot, especially since the last time I met with Naky, we talked a lot about our respective commitments. Making films means speaking out to say loud and clear what many people think but don’t dare to say out loud, especially women, children and vulnerable people. Actually, I think we must use this tool to try and carry a message and make things move, make things change so we can move forward together.

Hortense Assaga: How did you manage to impose yourself in this ‘masculine’ universe?

Mouna Ndiaye: It took a lot of time and a lot of work. Just like Naky, I come from the stage and there’s no better place to lay the foundations. A stage actor can play in a movie without any problem, but a screen actor isn’t necessarily going to be comfortable with the stage. For me, the stage is an essential step to shape yourself, to create yourself and to have bases. And I think it’s good to wear many hats!

Hortense Assaga: Last year, you were one of the jury members at the Cannes festival, a great symbol, a pan-African woman! How did it feel to be carrying this voice?

Mouna Ndiaye: It’s heavy, it’s huge! When you think of Cannes you think about glitter and parties: you’re happy. Afterward you sit down and you think. It’s a huge responsibility and the fear grows to find the right words, to be up to it, not to trip on the carpet!

Hortense Assaga: That’s the glittery clothing side!

Mouna Ndiaye: Exactly, that’s what you see first before trying to find out what’s behind. Fortunately, I have older sisters whom I asked for advice. I called on friends who are stylists, couturiers and live in Burkina. They helped me. I told myself, because of my many and varied origins, I needed to carry Africa in all its diversity. It wasn’t easy but I tried to fight and impose this diversity, first through the visual because culturally, we have a lot of things to show without often having the opportunity to show them off. I told myself it was the opportunity to showcase this diversity. That’s also what cinema and red carpets are for: carrying messages, carrying a culture, carrying a voice and, while we’re at it, we might as well use it and abuse it!

Hortense Assaga: Were you the little bird of curiosity?

Mouna Ndiaye: On that red carpet, I felt a little lonely, but this loneliness made me think about all my sisters, from all over Africa, and that gave me strength. I told myself that I was carrying this for all these women. I was really proud of it and it gave me the strength to do it.

Hortense Assaga: Does that represent a milestone in your career?

Mouna Ndiaye: Alone you go fast, together you go far. That’s how it was a big step. I didn’t get there alone. It’s all the women who were around me, all the women whom I saw before me who helped me to get there. I think we can change the image of women in cinema together. As Naky said, you don’t say yes to a role at all costs, it’s a choice. From the moment you make that choice, you need to stand for it. It doesn’t matter if it’s someone famous who offers you a role, if there’s something you don’t want to do in the movie, don’t do it. It’s not gonna stop you from moving forward somewhere else. I’m a huge supporter of movements against persecution, harassment, etc. but I think you can’t spend your time stuck on what’s not working. There comes a time when you have to ask yourself how you can make a difference.

Hortense Assaga: Nadia Rais, you’re an animation director. What brought you there?

Nadia Rais: The school of fine arts. Drawing starts with an idea, a sketch, characters. I often start with paintings. My research is based on my paintings. Animated cartoon, whether it is in Tunisia or what I saw elsewhere, is still quite marginalized. A woman doing animated cartoons, it’s very rare. In Tunisia, in Africa, in Europe. People often get animated cartoons and comics mixed up. A short film takes two years, so a lot of work, but at festivals, people sometimes ask me when I am going to make a real movie!

Nadia Rais: The school of fine arts. Drawing starts with an idea, a sketch, characters. I often start with paintings. My research is based on my paintings. Animated cartoon, whether it is in Tunisia or what I saw elsewhere, is still quite marginalized. A woman doing animated cartoons, it’s very rare. In Tunisia, in Africa, in Europe. People often get animated cartoons and comics mixed up. A short film takes two years, so a lot of work, but at festivals, people sometimes ask me when I am going to make a real movie!

Hortense Assaga: Do people also ask you when you’re gonna get a real job?

Nadia Rais: It’s already a question as an artist and now it is added as an art form! There aren’t many animation film festivals. So we’re often in the middle of fiction films but without actors for example. The approach is not the same. The way people identify is not done in the same way. We’re part of another group, and we sometimes feel like we don’t really exist. Our problem is not a woman’s problem. At least, in Tunisia, we’re very supportive of one other. We’re trying to fight against our marginalization, to make animation films exist in Africa, to create a festival. We don’t have schools either. The two current schools are technical ones: they teach 3D, modeling. But we don’t dwell on our problems. Nobody makes us do that, we love it. We create universes, we’re a bit in our imaginary bubble!

Hortense Assaga: In Briska, which got the golden stallion at Fespaco, you adapted an Egyptian tale about a new world. How do you ground your work in your Africa?

Nadia Rais: Tunisia has its own African, North African, Berber, Arabic identity so sometimes, you can feel left alone as we’re not 100% but we’re a bit of everything. Sometimes in Arabic film festivals, participants are shocked when they know I speak literary Arabic. It’s still in a context where we try to be part of a certain identity. But I see this as a richness as well. I don’t see graphic design as an identity universe. Whether it’s the music, the drawings, the characters, it’s my inspiration, things I love. I identify with all this richness, perhaps more with an African world than an Arabic one, but the adaptation itself is Arabic. It was a bit intentional. I adapted Tawfiq al-Hakim, an Egyptian. It became a half-Berber and half-African work. The project I have underway is similar, I’m working on a collage technique that is close to the African culture. You can create poetry from scratch. You give a piece of yourself and it gives a poetic dimension and that is something I encounter a lot in our African culture.

Hortense Assaga: The common point you all have is that you don’t ask for forgiveness before you do something, you just do it. Do you sometimes use your gender? Do you tell yourself because you are women you’re going to do that instead? Is your gender a weakness or a force?

Naky Sy Savané: I use it a lot. As a feminist, I can’t let things go on like that because there are other generations after me. If I have a choice, I pick scenarios that help women’s cause move forward.

Naky Sy Savané: I use it a lot. As a feminist, I can’t let things go on like that because there are other generations after me. If I have a choice, I pick scenarios that help women’s cause move forward.

Mouna Ndiaye: We used it in a positive way, you have to be very careful with words! As Naky, even if it comes from a very famous person, if there’s something I don’t want to do, I won’t do it. I’m not gonna use my charms to get a role. I point out what I can do, what I can bring to a film and that’s it. It’s not because I’m tall, I wear glasses and I have slanting eyes that I can have a role. It’s because of the context of the scenario, what I can bring to the film. The person must match the character. It’s not about appearance. As an actor, your role is not only to act, it’s to embody. An actor is like modeling clay, they transform, they understand the character and they embody them. It’s not just a physical appearance. We need to be able to understand that in our cinema. It’s not just about someone who matches a role that was written, it’s a whole universe. That’s why I love this job.

Marie-Clémence Andriamonta-Paes: Just a quick digression. Mouna talked about the responsibility of being on the Cannes jury. When I heard the list, I yelled ‘Ah! It’s Mouna!’ We felt proud. To have Mouna on that red carpet and in the deliberations, for me it had the same effect as Black Panther! It lifted me, it made me feel great. I was happy to see Mati Diop on stage. It was beautiful. These storytellers, these films were equal. We talk a lot about equality between women and men. I’d like to see people talking more about equality between cultures. It doesn’t mean that we should want to be Europe one day, no. There is indeed, and in animation as well, a creative power in Africa that the rest of the world needs. Only we can say that. We need to reverse the trend in this area.

Fatou Kiné Sène: To think that the 2019 winners won because Mouna was in the jury would be reducing the films. Similarly, highlighting the genre slightly undermines the merit. It is merit and not our status as women that allows us to « box » in the same category as men.

Debate with the »room’’

Aimé Besson: I’m dealing with cinema at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Paris. Do you have any concrete projects to put in place, perhaps on a continental scale, such as a festival or something that can highlight and participate in all the dynamics mentioned?

Olga Tiyon: I represent the 7 jours pour 1 film (7 days for 1 film) operation, a film workshop, a free itinerant operation in Africa to discover and promote tomorrow’s film and audiovisual talents. As Marie-Clémence said, there is in Africa an energy of creativity that needs to be shown. When we were looking for scenarios, men applied a lot more so parity was difficult. Out of 100 scenarios, 10 were from women and 90 were from men. So, by putting more emphasis on gender, it is easier for these women to enter areas where they didn’t have an easy access. So I join Aimé’s question about what your projects are.

Naky Sy Savané: In Côte d’Ivoire, we have the FESTILAG, the festival International du Film des Lacs et Lagunes (International Film Festival of Lakes and Lagoons), which led to the creation of the Association des Comédiennes Africaines de l’Image (Association of African Actresses of Image), a way to organise and structure our profession.

Catherine Ruelle: I’d like to ask a question about producers. Can Marie-Clémence talk about her experience?

Marie-Clémence Andriamonta-Paes: I became a producer out of necessity, out of passion for an idea, a desire for a film, and then I put all my energy into making it happen. In Africa, it’s particularly complicated because there is no training in production. You learn as you go along. Sometimes I call other women producers for advice, the network is working quite well. I don’t only produce women and I don’t only produce African filmmakers either. Yet, my films are always about our realities. For example, Haingosoa has just come out, and it’s neither made by a woman nor an African and yet it is a very sincere and powerful African woman story and the actress is great. For me, the difficulty today is the access to cinemas and audiences. There are so many films! There are sometimes as many as 30 films a week released in France! When you’re the distributor of a movie that sometimes took three to four years to be made, how do you manage to reach the audience? How do you make this film stand a chance like any other film?

Hortense Assaga: There are one a half billion people in Africa. Isn’t the issue here to further develop African audiences by reopening cinemas?

Marie-Clémence Andriamonta-Paes: There are a lot of projects in Africa to open multiplexes, but what will their programming be? In Madagascar, in Tananarive, they’ve just opened a CanalOlympia, as there are a lot of them elsewhere, their programs are 99.9% from Universal or Hollywood films. Our films have very limited access to these movie theaters, and despite all the great work of festivals, you can’t sum up the life of films in our countries to a day or a week of festival in these multiplexes!

Naky Sy Savané: People say to build an audience, but there is already a cinephile audience in Africa. In Côte d’Ivoire, there are more than 80 cinemas. I came into the film industry because there was a popular movie theater in our neighborhoods. Women who had never been to school would go to the 10 am, 2 pm, 4 pm, 6 pm, 8 pm screenings and they would even leave the market to go to a screening and go back to the market! The problem is that afterward the churches took over these movie theaters. Today, with FESTILAG, we are trying to revitalize the cinema industry and to work towards the reopening of movie theaters. I knocked on doors, I went to see the movie theater owners, because it was our fathers who built the movie theaters, but we were not successful. At 5,000 francs per ticket, people don’t go to the movies. Taxis, snacks… young people can’t bring their girlfriends. It’s not designed for them. Africa would benefit from reopening our popular movie theaters. There are headliners, there’s an audience, but we don’t give them the movies they want to see. We need our leaders to get involved.

Marie-Clémence Andriamonta-Paes: They’d have to realize it too. We’ve been told so many times: « When are you going to make a real film? » In the documentary industry, we’ve heard that for centuries, my own children have told me that! We have extraordinary films, films that deserve to be seen everywhere. I decided this year that Laterit Productions would be the distributor of Dieudo Hamadi’s The Billion Dollar Road, and we’ve learned that it made it into the Cannes selection. And that’s important! For all of us African filmmakers, that means it’s as good as Wes Anderson! I picked this film on purpose because when I go to Madagascar and ask for my film to be programmed, I get the answer: « We don’t show this kind of film here ». So there is a real programming work that needs to be done. And we have to restore the magic of cinema, on the big screen. We have to be smaller than this huge image! Just because you have a moving picture in your hand doesn’t mean it’s cinema!

Mouna Ndiaye: It is true that we don’t find the right people to work with us and that we become producers by default. So directors lose their creativity, and that’s dangerous. I’ve made documentaries where I ended up being a producer by default. As there were sensitive topics, no one wanted to work with me. But I don’t want to be a producer: I want to tell stories, stay in the artistic, creative side and have a producer who can help me. But, the situation being what it is in Africa, we’re not going to give up: I became a producer by default, I invested personal money to be able to make my documentaries. The producer is not necessarily the one who puts in the money, it’s the one who helps the project, the one who makes sure the project can go through financing, production and then distribution channels. It’s really someone like the mom or the dad who takes their child by the hand and walks them to school. So I don’t want to be a producer, I was one by default.

Now, it’s true that when you make a movie, you want it to be seen, before you even think about what it’s going to bring in. One thing we have to understand in Africa is that cinema is an industry. Making a film means employing a lot of people, it contributes to the development of a country. We have many projects. The Covid stopped us, but I know that a lot of people have written. Instead of creating new spaces, I think we need to strengthen what we already have: festivals and movie theaters. Here in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, a movie theater was demolished to build a mall. We can’t forget culture. You can’t say that there is no audience in Africa!

Fatou Kiné Sène: In the specifications that our governments sign with the multiplexes that Westerners are building in Africa, they should include a quota of African films and Southern films. The audience does exist. When there are one-off showings, movie theaters are full. At the AFCC, we give more visibility to all the films on our website africine.org. Here in Senegal, the African Women Films festival highlights the work that women do in Africa. Since 2013, the Senegalese Film Critics Association has established the women in cinema month. We also try to promote all the professions in the film industry and not only directing.

Houda El Amri: I think Mouna being on the jury was important because she was able to explain what was not necessarily accessible to the other jury members. The President of the Jury had stated from the beginning that for him, cinema was political first and especially social. It is therefore normal that our African films made a breakthrough last year. I think that we should not minimize our presence and on the contrary, strengthen our networks in these major festivals to make our African films known.

Mouna Ndiaye: I want to ask Aimé Besson, who was talking about projects, what are the projects of the Department of Foreign Affairs and vice versa, what can we do to get to you?

Aimé Besson: Audiovisual attachés but also French Institutes are encouraged to carry out actions in the field of equality between women and men, and not just broadcast French films but to do everything they can to support cinema, creators and artists. The Cinémathèque Afrique is also a partner that you all know. As I was listening to you, I was thinking of a more heritage program around women. The audiovisual attachés in charge can set up structuring projects with specific funds, the Fonds de Solidarité pour les Projets Innovants (Solidarity Fund for Innovating Projects), and we can imagine a project of this type around equality between women and men in the film industry.

Naky Sy Savané: The French Institute wasn’t interested in FESTILAG… We should also support initiatives and not only institutional festivals.

Aimé Besson: That’s what we do in Dakar for example with Dakar Court but you’re right: it can be extended to other places.

Hortense Assaga: Thank you to our speakers and thank you to all of you who are virtually connected for this first round table at the African Cinema Pavilion. Please continue to inspire us and enlighten our imaginations by telling our lives as Africans!

Special thanks to Lorrie Catel for her help with the transcription and translation into English (French version on the Africultures website)