(Test in french on the Africultures website) Euzhan Palcy presided over the jury at Dakar Court, which was held in Dakar from the 9th to 14th of December 2019. She accepted to come back to lead a masterclass and to respond to questions posed by the young cinephiles participating in the workshop “Talents 2019” who had been keenly following the events of the festival.

Olivier Barlet: Thank you, Euzhan Palcy, for taking the time to do this discussion. You have a remarkable position in the cinemas of Africa and the diasporas seeing as you are originally from Martinique and have also filmed in Africa. You spent a short time in Paris where you learned about film, and were already in contact with African filmmakers such as Sidney Sokhoma, so an interest in Africa from the start.

Euzhan Palcy: Exactly. I was 10 years old in Martinique when I first began to have the desire to make films! There weren’t any movie theaters, except for a parish hall where we projected a lot of American films, and a few French films. Very young, I asked myself where we were, us negros, in the image. I didn’t accept it. My grandmother told me, “you have 5 minutes to complain but one minute to tell me how you are going to change things.” I always kept that in myself. When I went to Paris to do my studies, I threw myself into the search for my African sisters and brothers. I had had the privilege of being chosen by the Municipal Cultural Office of Fort-de-France, which was led by Aimé Césaire, mayor, great poet, philosopher, historian, and professor. He was a son of Africa. Césaire knew the importance of culture. In the very center of Fort-de-France, in the floral gardens, he created the SERMAC, the Municipal Service for Cultural Action, municipal because it was not the French government who controlled it at the time. It was a Martinican cultural center: there, everything was possible, cinema, theater, the arts, music, etc. The classes were free. Crazy about film, after my baccalaureate, knowing no one, this was the ideal location for me to connect and discover films. 90% of the films shown came from Africa: this is how I discovered the works of Paulin Vieyra, Oumarou Ganda, Sembène Ousmane, Med Hondo, and others. When I went to Paris, it was very natural that I started looking for them. This is how I met Med Hondo and Sembène Ousmane. I had seen Soleil Ô…Mandabi… They appreciated but could not help me, being themselves in search of advice, but could give me advice.

You had your first experience in cinema at 17 years old, you had filmed The Messenger. Could you speak specifically to the young filmmakers present: howwe can begin in cinema in an improvised manner?

That’s true. I was very young when I wrote this first screenplay. It’s the relationship from beyond the grave of a young girl with her grandmother. She was what we call a Da, a Black woman who raises the children of Békés, the Whites who own plantations. A nanny, in short. She dies old, but has children and grandchildren, notably a young girl who is 17-18 years old to whom she appears in nightmares. Before dying, she had hidden her jewelry box, a very important object in the West Indies because there is gold, specifically the “collier-chou” or seeds of gold, a necklace with small balls and a clasp. The number of seeds gives the number of years passed in a master’s family. No one knew where the box was, which we look for when a woman dies. The grandmother indicates the hiding spot to her granddaughter in a dream but she is confused upon awakening. She decides to go where the old woman lived. I liked Hitchcock’s techniques for suspense a lot: the grandmother’s armchair begins to move. She speaks to the young girl but the young girl doesn’t hear her. Finally, after several tries, the latter is discouraged but when she passes by one of those little crosses that we often see in the West Indies, everything comes back to her and she can be “the messenger.” She gathers the village and the elderly are going to destroy the cross and find the box. The heirs of the White Creoles had decided to rid themselves of the banana plantation. Their workers and their children didn’t know where to go.

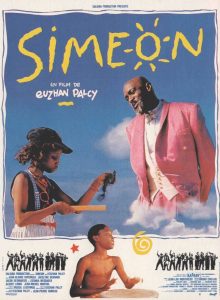

This gold allows them to ask the bank for a loan to create a cooperative to acquire the plantation. Like in my other film Siméon, the dead are not dead and see everything that happens on Earth.

And how did you make this film? Did you have a camera available?

I had never made a film, saw a lot of films at the parish hall, and read a lot. I had never, however, touched a camera. Michel Wuilstek, the artistic director of radio-television in Martinique, ORTF at the time, was a Frenchman who had lived in Africa for a long time. He was a music-lover: his hobby was the piano. He tried to make changes in television. I had turned up in his office to tell him that there needed to be more Black people on screen. You never actually saw a Black person or doudous in traditional outfits dancing when a president was visiting. When I was very young, I wrote poems and participates in a poetry program. That’s how I knew him. He liked the script but could do nothing: the cameras were only shooting the news. Amazed by the project, he told me that he had acquired a 16mm camera from a Canadian ethnologist who lived in Martinique with her Martinican husband, and proposed working as an operator. For the sound, my brother was introduced to Nagra. A Corsican who worked in television developing reels, Mr. Casanova, also had a 16mm camera and dreamed of filming. We had two cameras, and everything was done in the utmost secrecy. For the film, the reels were taken from the station’s stock and once used, Mr. Casanova developed them secretly. Christiane, the first Caribbean woman sent to Martinique as an editor because she married someone from mainland France, also became involved and I became her assistant. It took us six months to shoot the film, only the weekends because we were all working or in high school. We needed a lead actress, but the auditions weren’t great. I took it upon myself and my other brother played the lead male character. Once the film was finished, at 52 minutes, the artistic director suggested it at a programming meeting with his boss to replace yet another broadcasting of Madame Bovary. He watched it on the editing table. He was wrong about the title, believing that it was called “The Housewife.” But, convinced, the evening came, he announced the event before the broadcast, recovering the story by saying that they had opened their door to a young Martinican. And announced again “The Housewife!” It was really funny. It was my first film.

I had never made a film, saw a lot of films at the parish hall, and read a lot. I had never, however, touched a camera. Michel Wuilstek, the artistic director of radio-television in Martinique, ORTF at the time, was a Frenchman who had lived in Africa for a long time. He was a music-lover: his hobby was the piano. He tried to make changes in television. I had turned up in his office to tell him that there needed to be more Black people on screen. You never actually saw a Black person or doudous in traditional outfits dancing when a president was visiting. When I was very young, I wrote poems and participates in a poetry program. That’s how I knew him. He liked the script but could do nothing: the cameras were only shooting the news. Amazed by the project, he told me that he had acquired a 16mm camera from a Canadian ethnologist who lived in Martinique with her Martinican husband, and proposed working as an operator. For the sound, my brother was introduced to Nagra. A Corsican who worked in television developing reels, Mr. Casanova, also had a 16mm camera and dreamed of filming. We had two cameras, and everything was done in the utmost secrecy. For the film, the reels were taken from the station’s stock and once used, Mr. Casanova developed them secretly. Christiane, the first Caribbean woman sent to Martinique as an editor because she married someone from mainland France, also became involved and I became her assistant. It took us six months to shoot the film, only the weekends because we were all working or in high school. We needed a lead actress, but the auditions weren’t great. I took it upon myself and my other brother played the lead male character. Once the film was finished, at 52 minutes, the artistic director suggested it at a programming meeting with his boss to replace yet another broadcasting of Madame Bovary. He watched it on the editing table. He was wrong about the title, believing that it was called “The Housewife.” But, convinced, the evening came, he announced the event before the broadcast, recovering the story by saying that they had opened their door to a young Martinican. And announced again “The Housewife!” It was really funny. It was my first film.

You have to just dive in!

(applause) You have to go for it! It requires audacity! Don’t wait to be given things. When you’re thrown out the door, come back in through the window.

What were the reactions?

The television station was overwhelmed with letters complaining that there had not yet been such films and demanding other such films. It was the first time that the people of Martinique saw themselves in a film and where people spoke Creole. Creole was banned in schools. It was an event. They offered me the ability to continue but I didn’t want to tinker and was determined to train as a professional. So, I went to Paris to go to film school.

Marti, an Occitan singer, wrote in his memoirs that in the classroom there was a sign indicating, “it is forbidden to spit on the ground and to speak in dialect.” They were placed on the same level. Michel Le Bris said the same thing for Brittany. We find the same phenomenon of rejection of diversity.

Yes, and this was the colonial era! When we think that we still find reasons to say that there was good in colonization! In each class there was a painted wooden rectangle with the inscription, “Creole card.” The student on duty (designated for the whole week and in charge of the chalk, etc.) spied on the conversations of the students of his class during recess and if he found you speaking Creole, he handed you the card that you were obligated to take. You have to find a way to pass it on to another student before Friday night, otherwise you were condemned to go back to school on Saturday afternoon and write a hundred times, “I must not speak Creole” on paper. I took three pens to go faster by writing three lines at a time!

You spoke of the influence of Hitchcock. Serge Toubiana was present at the festival with us as the president of Unifrance. That’s a former editor-in-chief of Cahiers du cinema. At first, those who made the Cahiers were critics calledTruffaut, Rivvette, Godard, Rohmer, etc. who were part of the Nouvelle Vague. We called them the Hitchcock-Hawksians because they argued that the so-called popular cinema of Hitchcock and Howard Hawks was arthouse cinema. They defended American cinema. You being in America, does Hitchcock’s cinema exert a major influence?

Yes, incidentally, Get out by Jordan Peel, which knew great success, was very Hitchcockian as well! My brothers and I used to watch Hitchcock’s films and try to guess who the culprit was. We were passionate about that. Truffaut, Godard, Sembène Ousmane were also my masters.

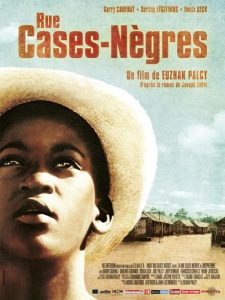

You made reference to poetry. What is striking is that your first two feature-length films, Sugar Cane Alley in 1983 and A Dry White Season in 1989 are book adaptations, the first by Joseph Zobel and the second by André Brink.

Why be arrogant or vain? If you find everything that concerns you in a book, it is better to acquire the rights: it saves you time. To adapt is not to copy: you create from pre-existing work. The book La Rue CasesNègres by Joseph Zobel does not fit into a film. We are obligated as always, by adapting, to take, to reduce, to recompose or sometimes to take liberties but without betraying the work!

It’s a film that you keep close to heart.

It’s a film that you keep close to heart.

Yes, my mother had put this novel in my hands. She wanted to keep me busy because I asked too many questions to the adults and it annoyed them. If they didn’t answer me, I asked why. They ended up calling me “Miss Why!” I was always with the adults because I was bored with the kids my age. This text triggered an eruption in my head and body: it was for the first time for me the story of the Negro from the plantations. We were never told about it in school even though it was our background. We were told that our ancestors were the Gauls… It was a cultural shock. This book haunted me. The kid that I was, I saw the movie in color! I was obsessed with it. After the collective prayer, I addressed a special prayer to the little Jesus to grow up quickly and make a film with it! However, I was told that Jesus did not want us to speak Creole! So one day I looked at him, and I said to him: “Dear little Jesus, I love you and I speak Creole to you, I’m saying to your face, punish me!”

And you made Sugar Cane Alley !

And you made Sugar Cane Alley !

I managed to make the film, but not without difficulty! First I had to find Joseph Zobel. He retired in Anduze, in the south of France, after spending a good part of his life here in Dakar as a teacher. He did not want to return to Martinique because he had suffered greatly under the colonization: the more black one was, the more despised one was. I brought the book my mother had given me. It was all worn. I showed it to him, with all the underlined passages, telling him that I already had several versions of the scenario and asking him to give me the rights even though I had no money. He listened to me and said that he was going to make a confession to me: “No one has ever spoken to me like this about my book, with such enthusiasm and such passion and anyway, I always said that we have to encourage young people.” He gets up and takes an envelope from on top of the television: La Station de Ste Lucie had asked him for the rights for an adaptation. It had pleased him but preferred to wait. “No doubt I was waiting for you!” He gave me an indefinite and free option! His editor, Présence Africaine, was furious: give his work to a beginner! And for free!

Following this, what was your relationship like?

Following this, what was your relationship like?

We bonded very strongly, him and I. For the character of Médouze, he put me in contact with Douta Seck, whom he saw well in the role. For Zobel, there had never been a return to the homeland. I wanted to bring him to Martinique and thus repair the injustice of the humiliation he had suffered. He said that he had had Africa and that we was not interested in it. I insisted, telling myself that I would wear him down. I told him about the scenes that I had transformed, completing what he had written. He gave me his blessing, saying, “the novel is mine, the film is yours.” After I finally found the money to finance this film with Black people, I told him to come because he had a scene to shoot. He played a character because I wanted him to mark this film. I finally convinced him. Zobel arrived in Martinique when I shot the payroll scene in Sugar Cane Alley. All the stars of Caribbean music were there. People cried, applauded, came to kiss him. He was very touched. The reception was so moving that people were swooning.

What character did he embody in the film?

Joseph Zobel embodied a character that I created, who was not in the novel. That of the Black parish priest. It was Césaire who had advised him to write novels. Zobel was a supervisor at Schoelcher High School where Césaire taught, and wrote football columns for Le Sportif, a newspaper much appreciated by the population. Césaire had spotted Zobel’s stories because they were remarkable. It was under the guidance of Césaire that he took up writing novels. The Negritude Movement influenced him to return to Africa. All his children were born in Africa.

We can’t bring up Sugar Cane Alley without talking about Darling Legitimus.

She had filmed 152 French films, of roles as maids, dancers, nannies. Never a role that suited her talent! Black people didn’t exist in French cinema! It was the grandmother of Pascal Legitimus who became a famous actor.

Were there other films that you absolutely wanted to make?

Were there other films that you absolutely wanted to make?

I absolutely wanted to put Sugar Cane Alley on screen, but also Cry, the Beloved Country by Alan Patton which discussed the living conditions of Black people in South Africa and to make a film about Toussaint Louverture, hero of the Haitian revolution who Napoléon imprisoned in the coldest prison in Europe, Fort de Joux, punished because he loved France but not a racist France, and in particular for defeating his army! As I often say, the greatness of a nation is measured by it’s ability to take ownership for its history with all of its components, the beautiful and the ugly. We have to take responsibility for the past in order not to repeat the mistakes.

Finally, Alan Patton’s book was already the subject of an adaptation.

Yes, of two even. But a friend showed me the masterpiece that is A Dry White Season by André Brink, an Afrikaner, teacher, history professor, who struggled against the Apartheid. He had refused to give the rights of his novel to Hollywood, which didn’t leave me with much of a chance. He was passing through Paris and agreed to meet with me. From the beginning, he told me that in South Africa, he secretly showed the film Sugar Cane Alley to his students. He gave me the rights without any problem! I was able to find a studio in Hollywood, Metro Goldwyn Meyer, in order to have the means to make the film that I wanted to make. It’s a Hollywood production, with Marlon Brando, but it’s a Euzhan Palcy film.

It was the impossibility of making the films you wanted in France that brought you to Hollywood?

It was the impossibility of making the films you wanted in France that brought you to Hollywood?

Unfortunately, yes. No one wanted Sugar Cane Alley. I came back to France with only Siméon a fantastic Caribbean musical then Parcours dedissidents, a documentary on on the West Indians of the Second World War who responded to General de Gaulle’s call to action on 18 June. It was an audiovisual memorial that gave rise, 65 years later, to the recognition of their courage before their death. But Hollywood also has its own way of seeing things and it’s really not a sinecure if I may say so! I received multiple proposals after A Dry White Season but mine did not pass… For them Black people were not bankable and especially if the main character was a woman. But despite racism and sexism, you’re more likely to run into someone who understands things and is going to take the project to the end. On each new project, we go back to square one.

You also wanted to pay homage to Césaire with a documentary trilogy.

You also wanted to pay homage to Césaire with a documentary trilogy.

Exactly. I wanted the youth to be able to discover the founders of Negritude. Césaire’s words are words for yesterday, more than ever for today and tomorrow. They carry strength and hope! André Breton said: « The word of Aimé Césaire, beautiful as the nascent oxygen! »

Discussion with the room

Question: Thank you for your engagement and humanism. Does cinema adaptation have the right to betray the book?

An adaptation respect the original work. We can’t make up anything. You can transform but not distort. Adaptation is a writing technique, an art. It is not plagiarism. A character will sometimes become mixed, representing several characters of the story. This is not to betray the work. An example: in the novel, the kid is lying on the grandmother’s bed and reading a book. In the film, I put a work of Pagnol, Topaze. In my films, nothing is free. In voice-over, the kid says that the grandmother finally allows him to lie down on his bed. It’s not in the novel but everything in the novel says it.

The prohibition was cultural, out of respect for the elders. This allows him to say that his grandmother has changed. The gesture speaks, the kid understands. You have to put things in pictures: cinema is not made to talk! The Naked Island by Kaneto Shindo does not have a single piece of dialogue and yet what a masterpiece!

Question: the Cinébanlieue cinema club shows films each weekend: we would be happy to see your films!

You have my films, that’s certain.

Question: What books should we read?

Read your writers, you will find the godsends! Me, I dream of bringing to the screen, with Africans, the history of Sundjata Keïta!

Question: Have you received threats being a combative woman who defends Black people?

The camera is my “miraculous weapon,” to use a Cesarian expression! We are here to show that White people are not the only ones who know how to get things done and who have the right to be on the big and the small screen! I support diversity and that we work together! Of course that can’t please everyone, but that doesn’t matter to me!

Translation : Madelyn Colvin