(translated by Madelyn Colvin from the article in french on Africultures) Ladj Ly et Djebril Zonga presented Les Misérables as a preview showing at the Dakar Court Film Festival on December 12th, 2019. The following day, Ladj Ly responded to questions in a fully-packed room at the French Institute of Dakar, notably those of young filmmakers taking part in the festival’s workshop “Talents 2019.” The session was preceded by the projection of 365 jours à Clichy Montfermeil. O.B.

Olivier Barlet: What’s striking in the film that we’ve just seen is the similarity with the way you film Les Misérables, seen last night: a shoulder rig, movement, rhythm… Why did you want to show it to us before this meeting?

365 jours à Clichy Montfermeil

Ladj Ly: It’s the first documentary that I directed. It’s where everything began. I started out my career as an actor. I wasn’t very at ease and I preferred to be behind the camera. This one takes place in Montfermeil, where I live. There were the riots of 2005, in front of my home, in my road. Naturally, I went outside to film. I think that this went on for two or three days: I made archives for an eventual short film. And finally, I filmed for a year everything that happened: the starting point of the riots following the death of two kids who were fleeing the police, Zyed Benna and Bouna Traoré, and all of the associations, all of the movements that were created. I followed all of these participants but no television chain wanted it. At the same time, every television chain in the world wanted to make images even though I was the only camera that could film from the inside. The majority wanted to buy back these images from me. I refused to sell them and decided to make my own film. Seeing as it had not been broadcast, we released it on DVD and it is now available for free on YouTube. The approach was to testify to what we could live during this year, to have a point of view of the inside and to give voices to the residents. Journalists were looking for images that were a little sensational for their subject and didn’t dawdle. It was important to take the time to understand and go to the meeting of all of the protagonists and to bear witness to what we could live during this year.

Olivier Barlet and Ladj Ly: Masterclass at the Dakar Court Film Festival 2019

There are a number of filmmakers in training in the room: maybe tell us what was the stimulus that made that you, youth in the ghetto, of Malian origin, you knew of a camera?

Being a kid, at 7 or 9 years old, I was pals with Kim Chapiron, who is the son of Kiki Picasso, a graphic artist, and Romain Gavras whose father is the filmmaker Costa Gavras. At 14 or 15 years old, we decided to create the collective Kourtrajme (“court métrage” backwards). We weren’t known in the history and characters of French cinema to make our own films. We made several short films that knew a certain success. At that time, I was an actor and played in all of these films, notably Satan by Kim Chapiron with Vincent Kassel in 2016. I bought my first camera at 17 years old and I never stopped filming. I recorded this area a lot and for several years, I made copwatch seeing as I lived in a relatively lively neighborhood. The police committed a lot of abuse. I filmed systematically for more than 10 years.

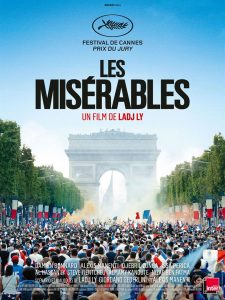

One time, I filmed an error made by a police officer. The police had broken into a family’s home, had seized the kid and beat him severely with shots from a flashball and police batons. We endured an enormous amount of pressure. I had been summoned to the police station so that I would not diffuse the video. As soon as I had left, we discussed it with my group of friends and we decided to put it on the internet. This triggered an IGS investigation, the police of the police, and this was the first time that police officers were condemned following the diffusion of a video. I had very particular relationships with these two officers: I had about fifty or so hours of video of them. I don’t count the number of times of being in custody, the number of times where I broke my camera, the number of police raids… This had been a difficult period of time. I realized the power of images and it gave me the desire to make Les Misérables, which could touch more spectators than the documentary. It’s a film that took me nearly 10 years to put together, a real obstacle course. When we attack the suburbs, minorities, police violence, social misery in general, it’s very complicated. I come from nowhere and I didn’t go to film school. Two years ago, I met the producers, which was new for me: I came from the principle that I made my films alone, from the writing to the filming, total independence. We got along well. I explained my process to them, they knew my work. They gave me full rein. I found the approach interesting. I made the short film Les Misérables in 2017. It was successful, the Césars, 14 or so awards. Despite this success, it was very difficult to put together the full length feature. We would have needed three million euros, we did it for 1,4 million. That’s a small savings for a shoot in France. Everyone helped out, from the residents to the mayor. There was a beautiful energy. With the result, we could be nothing but proud: in competition and an jury award at Cannes, the Golden Globes, and underway for the Oscars… It’s just out of control what’s going on with this film!

One time, I filmed an error made by a police officer. The police had broken into a family’s home, had seized the kid and beat him severely with shots from a flashball and police batons. We endured an enormous amount of pressure. I had been summoned to the police station so that I would not diffuse the video. As soon as I had left, we discussed it with my group of friends and we decided to put it on the internet. This triggered an IGS investigation, the police of the police, and this was the first time that police officers were condemned following the diffusion of a video. I had very particular relationships with these two officers: I had about fifty or so hours of video of them. I don’t count the number of times of being in custody, the number of times where I broke my camera, the number of police raids… This had been a difficult period of time. I realized the power of images and it gave me the desire to make Les Misérables, which could touch more spectators than the documentary. It’s a film that took me nearly 10 years to put together, a real obstacle course. When we attack the suburbs, minorities, police violence, social misery in general, it’s very complicated. I come from nowhere and I didn’t go to film school. Two years ago, I met the producers, which was new for me: I came from the principle that I made my films alone, from the writing to the filming, total independence. We got along well. I explained my process to them, they knew my work. They gave me full rein. I found the approach interesting. I made the short film Les Misérables in 2017. It was successful, the Césars, 14 or so awards. Despite this success, it was very difficult to put together the full length feature. We would have needed three million euros, we did it for 1,4 million. That’s a small savings for a shoot in France. Everyone helped out, from the residents to the mayor. There was a beautiful energy. With the result, we could be nothing but proud: in competition and an jury award at Cannes, the Golden Globes, and underway for the Oscars… It’s just out of control what’s going on with this film!

And for the moment 1,2 million tickets sold in France.

Yes, around that.

You go from auto production with a small budget to a large budget. It’s really another level…

It’s certain that that changes the deal. 1,4 million, that’s already a large sum. A team of 50+ people… This may seem pretentious but I found it fairly easy to be supported, to have people on every position in the making of a film. With an idea that makes sense, a scenario and being well supported, it’s not that complicated. I encourage young people. I met some of them at Dakar Court and Cinemarekk, we exchanged quite a lot: I encourage them to develop their short films. We started from nothing, without financing. You have to be passionate above all, rather than wanting to make money.

It’s certain that that changes the deal. 1,4 million, that’s already a large sum. A team of 50+ people… This may seem pretentious but I found it fairly easy to be supported, to have people on every position in the making of a film. With an idea that makes sense, a scenario and being well supported, it’s not that complicated. I encourage young people. I met some of them at Dakar Court and Cinemarekk, we exchanged quite a lot: I encourage them to develop their short films. We started from nothing, without financing. You have to be passionate above all, rather than wanting to make money.

You wrote the screenplay for the short with Alexis Manenti, who plays the corrupt policeman, and for the feature length you called in a professional.

Yes, Giordano Gederlini. You can’t improvise yourself as a screenwriter. It’s a real profession in itself. You might not be incapable of it, but it would take a lot of time: you need experience. We bring the material, the ideas, and the screenwriter helps us structure the script.

And on the set, did the actors have room for improvisation or did you have a fully written text?

The text was very well written. I wanted to stick to it but once they had really gotten into it, I would leave them an extra sequence where they had total freedom and could even improvise. It was full reign where they could even get out of the text to express themselves. This resulted in a lot of sequences with improvisations and it reinforces the realistic side of the film. I wanted to bring this documentary side to fiction, the shoulder rigs very close to the people. These are real stories that I tell, the lives of my family and friends and of the residents.

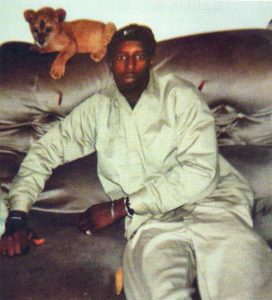

It’s real and at the same time the story of the lion seems completely fantastic, fabulous, which fits into the reality of the film.

In fact, it’s a real story. When I was 17, I had a buddy who stole a lion cub from a circus. (he looks for a picture in his cell phone) I don’t know if you see it but there I was very young with the cub! (cf. photo opposite) I start with the stories of my friends. Even the final scene, it happened in my stairwell. The kids attack the policemen because when they get beaten up they can’t file a complaint because it’s the same policemen who receive them. As a result, they take justice into their own hands.

In fact, it’s a real story. When I was 17, I had a buddy who stole a lion cub from a circus. (he looks for a picture in his cell phone) I don’t know if you see it but there I was very young with the cub! (cf. photo opposite) I start with the stories of my friends. Even the final scene, it happened in my stairwell. The kids attack the policemen because when they get beaten up they can’t file a complaint because it’s the same policemen who receive them. As a result, they take justice into their own hands.

The film is tense from the beginning but the action really only starts after about forty minutes: you prefer to set up the geography of the neighborhood by following the initiation of the new policeman.

Yes, I come from documentary filmmaking and it contradicts the fact that the trigger has to come after five minutes. Very few people know these neighborhoods, don’t set foot in them: I wanted to take the time, to settle down. We’re immersed.

The policemen in the film are human, even if they are problematic.

It’s important for me not to take sides, not to judge my characters, to stay in reality. In the police, there are some who behave well and do their job and others who behave less well. The Misérables are the residents but also the policemen: they work in difficult conditions with very low wages, and often also live in housing tenements. I’m not here to defend them, but that’s the reality.

It’s important for me not to take sides, not to judge my characters, to stay in reality. In the police, there are some who behave well and do their job and others who behave less well. The Misérables are the residents but also the policemen: they work in difficult conditions with very low wages, and often also live in housing tenements. I’m not here to defend them, but that’s the reality.

The film is focused on young people, and since it’s a warning film, it’s in relation to this generation that you make a big battle cry.

Issa Perica (Issa) and his group in Les Misérables (LM)

Of course, it’s a film that discusses childhood, about the place of young people in neighborhoods. They are left to their own devices from a very young age: the associations that used to take care of them no longer have any funding, and they don’t even talk about culture anymore. I wanted to sound the alarm. The situation is critical. The film takes place during the summer: for two months, they are released in the ghetto. During the Cannes Film Festival, I called on the President of the Republic to see the film, since politicians are the ones who are primarily responsible. He had invited us to the Elysée Palace, I refused because I wanted him to come to Montfermeil. It would have made sense for him to come to the neighborhoods himself. We ended up sending him a dvd: he saw the film and it seems that he was upset and asked all his ministers to find solutions. We’ll see what happens.

Steve Tientcheu (« The Mayor ») in Les Misérables (LM)

In your documentary, we see the real mayor of Montfermeil, who by the way does not even stop the engine of his car, but in Les Misérables, he is absent, just like the State.

They were never there. There is a facilitator that we call the mayor who runs the neighborhood. And a whole organization has been set up.

Discussion with the audience

Demba Sissoko (journalist): Did you make your short films and documentaries while waiting to make your big project?

Ladj Ly : Yes, I’ve had this desire to make films since I was a teenager. I started with documentaries because it’s the simplest, then fiction. I learned and learned, until I found money for the first feature. My buddies in the collective had made feature films and that put pressure on me!

Penda Diatta (Talents 2019): What was the reaction of your Malian parents after seeing 365 days in Mali?

I had set up a series so the principle was to take the time and spend a year there. I didn’t stay in Mali for a year but I am there four or five times for weeks or a month. I’m not sure my mother saw it because I don’t show her everything. However, she saw Les Misérables and was very happy.

Augustin Ngom (screenwriter): We had an exchange this morning with some veterans of our cinema who, with great fervor, advised young people to take the time to be assistants on the sets before putting on the label of director. I’m self-taught too, like you. In return, what advice would you give to the elders?

( laughter) You want to get me in trouble!

Olivier Barlet: Actually, what the elders advised was to have patience…

Patience is important! I did all the jobs, I served coffee, I did the control room… It’s the most unattractive job but the most interesting because it allows you to understand the whole machine. Be a stage manager! You learn a lot. You can’t become a director right away.

« The Mayor » and his acolytes in Les Misérables (LM)

Question: In your documentary, do you first come to an agreement with the people that you film?

I take out my camera and film. I’ve always done it like that. If the person is not happy, so much the better, because it will create movement. I don’t put a barrier on anything.

Mame Wary Thioubou (director): Did Les Misérables help change things in Les Bosquets?

I don’t have much feedback since the film was released just over a fortnight ago. All the kids who acted in the movie now want to make movies! It allows them to think about doing something other than the manual jobs they are destined to do.

Selly Rabi Kane (stylist): It’s important for our generation to see that you can be in the learning process and do it at the same time. How does the Kourtrajmé school encourage people to make films?

It has been in operation for almost two years. We train to the professions of the cinema: script, production, directing, editing, post-production, photo art. For the first year, we trained about thirty young people, produced five short films and developed two feature films, one of which is a series. The second class has 45 students. The idea is to train them, accompany them, produce the films to follow the students. Of the 30 students in the first promotion, 22 or 23 have a job. One is currently shooting a series in St. Louis, Senegal. We are going to send two students to assist him. Three students are shooting a documentary for France Television. Seven students are developing their short films. We are accompanying them. We try to push them 100% so that everyone has a project.

Gildas Magnim Madang (Talent 2019): We see in the film a picture of you with a kind of bazooka.

Picture of JR on a wall in Les Misérables: Ladj Ly with his camera

Yes, that’s me. It’s not a weapon but my camera. It’s a picture of the artist JR. He photographed me 15 years ago and I think it represents me well. It’s a wink that we wanted to make to the artist in this sequence.

Olivier Barlet: But it’s really the camera that’s a weapon!

Of course. Somehow it was my weapon. It allowed me to testify, to render justice when the police officers committed this blunder, to protect myself too: when I was doing copwatch and I took out my camera, it calmed everyone down. People would see me coming from far away and shout: « There’s Ladj! ». Everybody would calm down. I had become the police’s pet peeve. They knew that it was evidence that could be disseminated on the internet.

Question: Your knowledge of the field made it easier. In another setting, would you have the same ease?

« The Mayor » (Steve Tientcheu) surrounded by young people in Les Misérables (LM)

It’s true that it helps a lot. A team around you helps as well. Everything was tied up before shooting. I put pressure on myself and finally, it was fluid on the set.

Question : How do you proceed with the actors?

I challenged myself not to work with stars. Only Damien Bonnard, the new police officer, had experience, and of course Jeanne Balibar who plays the commissioner. Alexis Manenti had done some short and supporting roles and for Djebril Zonga, a former footballer and modeling career, this was his second film. It was the first time they were in the lead. There were a lot of exercises, we put ourselves in situations, we were also in immersion with the policemen because it was important to have their opinion. The actors filmed with the BAC teams, with the departmental teams, they took the time to go to the police stations to discuss with them.

Next question: And with the less professional ones?

The bet was to unveil new faces and work with the people of the territory. None of the kids in the film had ever been in the movies. A lot of work was done beforehand after the casting. We had a room where they came every day to train. I talk a lot with the actors. None of the kids had read the script. You tried it out on the spot. If we had to redo the take four or five times, we’d do it. It was pretty accurate and precise. I work a lot by ear: I don’t always look at the screen. When it sounds right, you can hear it right away.

Baba Diop (Senegalese critic): René Vautier had also used his camera as a weapon when making Afrique 50. Your cinema is part of the tradition of intervention cinema. Have you seen Vautier’s films in Africa and Algeria, the films before and after 1968, etc., to fall into this lineage?

No, I haven’t seen them but I would love to. But I’m not a cinephile at all. I watch very few films. I start from the principle that I want to make my own films, with my own way of filming, without going into frames and wanting to do what everyone else does. I have a rather special approach: I watch one film a month, and then some! I see the important films, but I try instead to stay focused on what I do and tell my stories with my touch.

Question: Congratulations on the film. What struck me is that each character brings something strong with his own particularity. Also because the film allowed us to travel and see neighborhoods that we never see in the picture here. I’ve noticed that you use zoom and travel shots: is this for a particular meaning? Besides, you didn’t go to film school but you’re creating one today: isn’t that paradoxical?

( laughter) I didn’t get a chance to do any! If I had applied to the Femis, they would never have taken me: you need a baccalaureate + 2 or 23, it costs a certain price, it lasts three years. I would have liked to go to film school at 18. I made a school that is not classical, with a different approach: a different vision, a way of producing, directing and filming. We started in the 96’s, at the very beginning of the digital era. We bought the very first cameras at half price. This allowed us to zoom in and use wide angles: we had a different way of filming. That’s what I’ve kept in the film: very close to the people, camera on the shoulder, lots of movement, zooms… It allows you to bring back dynamics. As soon as I set foot in the room, I get bored. The only time I inserted myself was in the bar sequence between the two policemen, Pento and Gwada, which is the scene I had the hardest time shooting. As soon as it’s static, I get bored.

Claire Diao (journalist and distributor): You’re not the only one in France who’s fighting because you went to feature film without going to film school, but you’re the first to be nominated for an Oscar. Do you have the impression that the French film industry is opening up, or do you feel, given that you’ve had a lot of doors opened to you, a kind of hypocrisy? Is your career path still an exception or do you have the impression that it’s getting normalized and that people are benevolent and that other filmmakers will have more room?

Olivier Barlet: Do you mean if the industry is opening up to diversity?

Claire Diao: I don’t know that it’s diversity, but let’s say we accept all French people whoever they are.

It is a difficult environment to access. For my film, it has been the journey of the fighter. But I have the impression that with Les Misérables, little things move. The CNC did not support the film but changed its president. I met him: he wants to make the lines move. He would like there to be more diversity in the commissions. I hope this will mean more openness.

Ladj Ly during the masterclass

Question: Can you be a good director while holding the camera?

I have always filmed and holding the camera allows me to be in my element. I absolutely wanted to film for this film too. But I finally met a cinematographer with whom I got along really well. I showed him all my films and he understood what I wanted. We did some tests, I trusted him and let him have the camera. And in the end, I think it’s much better: it allows me to stay focused on directing and the acting. So I would say that if you have a cinematographer you’re happy with, take advantage of it!

Question: We are students at the Media Centre in Dakar, trained by filmmaker Moussa Touré, who tells us that the best way to learn to film is to watch films. Do you have any references that allowed you to make Les Misérables??

I watch very few movies but I have two references: The Hurt Locker and Detroit by Kathryn Bigelow, which inspired me. I really encourage anyone who wants to be a filmmaker. The potential for stories in Africa is enormous. Platforms like Netflix or Amazon are currently positioning themselves in Africa. There will be a lot of money and producers in the next few years: hang in there, it will be long and hard but you will get there!