At the Clermont-Ferrand International Short Film Festival which took place online from 29 January to 6 February 2021 due to the covid-19 pandemic, Claire Diao animated as usual an hour of debate with the filmmakers of the African Promises programme, this time only three: Karabo Lediga (South Africa), Morad Mostafa (Egypt) and Anthony Nti (Ghana). Full transcript. Translation in french on Africultures.

Tim Redford: Hello, everyone. Welcome to this roundtable with the directors of the A3 program African Promises: Seeds of Heroes. My name is Tim Redford, I’m the International Coordinator of Clermont-Ferrand International Short Film Festival, which started yesterday entirely online. The program is part of our African Perspective Section, which is celebrating it’s 30th anniversary this year. It highlights short films made by promising directors from the African continent or from the diaspora. This program has been labelled by the French Institute as part of the Africa 2020 cultural season. Before handing over to our fellow traveler and friend Claire Diao – journalist specializing in African cinema and member of the selection committee here in Clermont, who will introduce you to the participants and moderate the roundtable – we’re delighted to welcome N’Goné Fall the general commissioner of the season who wishes to tell us a few words about Africa 2020.

N’Goné Fall: Good evening or good afternoon, everybody, depending on where you are. It’s a great pleasure to be part of this panel, and just to be able to give you a few insights about the Africa 2020 season which started in December, and is going to roll out until July of this year. It’s a season dedicated to the youth, and to women. It is about the entire African continent, and African’s living abroad. It is about, “Who are the change makers on the continent?” and how they are innovating, looking at a series of questions, and issues, and challenges that we’re facing in this 21st century on the continent. It includes all the activities, whether it’s culture, science, entrepreneurship, economy, all over the continent. All the projects are Pan-African, and pluri-disciplinary. I’m very, very happy that despite the pandemic some people are being very innovative, and putting their projects online. I’m happy to be part of this roundtable as an observer. Thank you all.

Tim Redford: Claire, I’m handing over the mic to you to introduce our friends. I’m delighted to have here next to me Anthony Nti. Anthony is a member of the international jury this year, so he’s one of the very few guests we have here at Clermont-Ferrand. Enjoy the roundtable and I’ll see you later. Thank you.

Claire Diao: Thank you. Hi, everyone. Really pleased to welcome you to this online Clermont-Ferrand International Short Film Festival. This year we have a special selection related to the season Africa 2020, called Seeds of Heroes. It is composed of 4 shorts, and we have the pleasure to receive three of these filmmakers tonight. I will start by the lady, Karabo Lediga.

Karabo Lediga: Hello.

Claire Diao: Welcome. So, Karabo is a South African writer and director for television and film. Her short, What Did You Dream? premiered in competition at Clermont-Ferrand last year, and was also in competition at the Palm Springs International Short Films Festival. Karabo has written for the first African Netflix original series Queen Sono, across twelve seasons of the twice international Emmy-nominated satire show Late Nite News with Loyiso Gola, and three seasons of the comedy series Next of Next Week. Karabo has worked as a writer, director, content producer, and performer. Her directing work also includes two seasons of the sketch comedy show The Bantu Hour, and situational comedy The Mayor. Her tv writing work also includes South African film and television award winners Lockdown, MTV Shuga 5, and the four-part mini-series, Emoyeni: Insanguluko, and most recently as development writer for animated series Queens for Netflix animation and Wild Sheep. Karabo is currently in development of her debut feature film, titled Sabbatical. Welcome onboard.

Claire Diao: Welcome. So, Karabo is a South African writer and director for television and film. Her short, What Did You Dream? premiered in competition at Clermont-Ferrand last year, and was also in competition at the Palm Springs International Short Films Festival. Karabo has written for the first African Netflix original series Queen Sono, across twelve seasons of the twice international Emmy-nominated satire show Late Nite News with Loyiso Gola, and three seasons of the comedy series Next of Next Week. Karabo has worked as a writer, director, content producer, and performer. Her directing work also includes two seasons of the sketch comedy show The Bantu Hour, and situational comedy The Mayor. Her tv writing work also includes South African film and television award winners Lockdown, MTV Shuga 5, and the four-part mini-series, Emoyeni: Insanguluko, and most recently as development writer for animated series Queens for Netflix animation and Wild Sheep. Karabo is currently in development of her debut feature film, titled Sabbatical. Welcome onboard.

Karabo Lediga: Thank you very much.

Claire Diao: Then from the south of Africa we will go north to Egypt, to welcome Morad Mostafa. Morad, are you here?

Morad Mostafa: Hi.

Claire Diao: Hi there. So you’re with your producer who can also translate from Arabic to English for you?

Morad Mostafa: Yes.

Claire Diao: Welcome to both of you. So, Morad Mostafa is an Egyptian director, born in 1988 in Cairo, Egypt. He studied film directing at Cinema Palace in 2008, and at other film-making workshops. He has worked in the film industry since 2010, as an assistant director with several directors such as, Mohamed Diab, Sherif Elbendary, and Ayten Amin on Souad which has been selected at the Cannes Film Festival 2020. In 2019, Morad directed and wrote his first short Henet Ward, which had its world premiere in the Clermont-Ferrand International Short Film Festival, and was awarded worldwide. His second short, What We Don’t Know About Maryam does it’s world premiere currently in Clermont-Ferrand. Welcome onboard Morad.

Morad Mostafa: Yeah, thank you. Nice to meet you Claire.

Claire Diao: And the third person for this panel, is the well-known Anthony Nti, and I say well-known because he won an award last year, and he’s a member of the jury this year. Anthony, are you here?

Anthony Nti: Yes, I’m here.

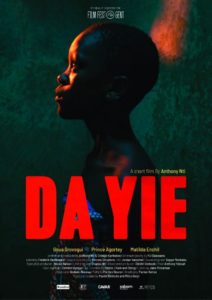

Claire Diao: Okay, so, for the ones who do not know, Anthony is a Belgian-Ghanaian director. In 2012 he joined the Royal Institute for Theatre, Cinema and Sound in Brussels. His shorts Only Us, Kwaku selected in “Regards d’Afrique” in Clermont-Ferrand 2015, and Boi have been selected worldwide. His last short, Da Yie won the Grand Prix at the Clermont-Ferrand International Short Film Festival last year, and has been selected in more than 100 film festivals. In parallel, he directed the viral video BLACK MAGIC (Black Harry Potter) for Yung Mavu, which received more than 30 million views on YouTube. Congrats. In 2020 he co-wrote and directed the mini tv series Shaq for the VRT channel. He is currently working on his first feature, Postcard, which won the second award at the Sam Spiegel Film Lab. He also develops Clemenceau, a tv series, to be co-directed with Chingiz Karibekov, co-script writer on Da Yie, and Mohamed El Hajjouti. Welcome onboard, Anthony.

Anthony Nti: Hello, welcome.

Why do you make cinema?

Claire Diao: So, we have one hour to talk about your films, about cinema, about short films, and Clermont-Ferrand. So I will start by one question, and then the three of you answer. Maybe we will be gentle and start with the lady. So, Karabo, why do you make cinema?

Karabo Lediga: I’ve watched so much cinema and television in my life, and I didn’t see a lot of myself in it. And I’ve had quite a charmed life, and a life that is tumultuous because I grew up in apartheid, but I knew that my story didn’t end there. I knew that my story was broader and quite charmed, and was quite nuanced, and was quite sweet, and funny, and quirky, and embarrassing. I wanted to be part of a generation that tells a different story about Africa. Not one that doesn’t include our history, but one that includes our softness as well. So I initially loved cinema but I also wanted to be a part of a generation that tells a different story about Africa, that completes the entire narrative. Because I think that the entire narrative is quite off-balance. So, it’s fun but there’s a duty in me that wants to tell quirky stories about boys, and girls, and grannies, and uncles, and just funny stuff. That’s why.

Claire Diao: Morad, after being an assistant, you became a director. So why do you make cinema?

Morad Mostafa’s Translator: Well he said that he started to make cinema as an assistant director, but that wasn’t the end of it. He made it for another purpose. Well, as a filmmaker, he wanted to express his point of view and he didn’t seem to find a feature film as a suitable way to start, especially being from here. He had ideas that could be made as short films, that’s why he started with short films. To express what he sees and then translate it into cinema, and that’s why he’s doing it, and continuing to do it, and will continue to do it. He wanted to observe and master the society he’s living in, whether he’s going to do that with representing Egyptian or non-Egyptian people, as Egypt is full of other nationalities, and very interesting things to talk about.

Morad Mostafa’s Translator: Well he said that he started to make cinema as an assistant director, but that wasn’t the end of it. He made it for another purpose. Well, as a filmmaker, he wanted to express his point of view and he didn’t seem to find a feature film as a suitable way to start, especially being from here. He had ideas that could be made as short films, that’s why he started with short films. To express what he sees and then translate it into cinema, and that’s why he’s doing it, and continuing to do it, and will continue to do it. He wanted to observe and master the society he’s living in, whether he’s going to do that with representing Egyptian or non-Egyptian people, as Egypt is full of other nationalities, and very interesting things to talk about.

Claire Diao: Thank you. Anthony, before winning the Grand Prix you were already directing films. So why do you make cinema?

Anthony Nti: I was born in Ghana and I lived there and I moved to Europe, and I still have a lot of connection and I go back and forth. For me, it always felt like the only place that you kind of feel safe. I mean, safe is a big word. It’s on the airplane because in Ghana I am Ghanaian, but, you know, there are differences, and in Belgium I’m not completely a Belgian. So, for me, filmmaking and telling stories was something that had been in my Ghanaian culture. My grandma told a lot of stories, and storytelling is something very cultural where I come from, so the beautiful thing about cinema is that you can communicate to the whole world without necessarily speaking the same language. And that was for me, like, “Wow, so you can tell a story here and somebody on the other side of the world can understand, and sympathize, and go with you?” That kind of power I felt like could be used in an interesting way to show stuff, like Karabo was saying, there are different perspectives. I felt like I wanted to tell stories that could touch everybody from around the world, but it’s a different perspective. That’s what I’m trying to do, yeah.

What do you think about the short format?

Claire Diao: So currently in Clermont-Ferrand, can you please all let me know what you think about the short format? Maybe Anthony to start? Or Karabo?

Karabo Lediga: I think coming from where I come from the batches are not huge, but the short form, it lets you say so much in such a short space of time. It’s not an insanely cheap format but it’s a very difficult one for you to be succinct and shortened, and to be to the point is such a powerful ability as a filmmaker. Having been to Clermont-Ferrand last year, it blew my mind, so many films that said so many moving things in such a short space of time. First of all, I think it’s accessible to a lot of people, and cinema is not often accessible, and that it exhibits so much skill from around the world, especially from what I saw yesterday and it’s so powerful to be able to be short. Even in speeches, long winded people are not the most impactful but I think short is so far out you have to think every minute and I respect and bow down to the short form forever and ever and especially after having been to this film festival that dedicates so much effort and love to the short form, it means everything.

Morad Mostafa’s Translator: He has always been interested in short films, and he thinks short films are more interesting. As you have to tell your story in a very compact time and very short time, and affect people in that time. And sometimes it doesn’t take a feature to be straight to the point. A short is enough and it’s very to the point. While he’s always been passionate about watching short films and it was very interesting for him, and he doesn’t think of it as a very separate step to making features, it’s its own kind. It’s something that is separate from features. You can still make features and shorts because it has its own language. Then you can make reference anytime and it has its own language and you can always make it.

Anthony Nti: I see short films as audio visual arts because you have short films, and video clips, or short films in commercials. I just saw short films as an audio visual art and if you want to make a longer film it kind of starts from the same base, you know. So a short film, I can just speak for myself, for me I see short films as more just telling your story. I see it as brick for brick because I want to do longer stuff. And, and sometimes you can show what you can do in a shorter format and I’m super happy that that’s possible because imagine you only had to make longer stuff or other stuff to be seen, nobody will be here. So, just having a place for shorter stuff. It’s super great but I see it as difficult as you don’t know if you can tell the story. There are people, they can maybe tell a good 20 minutes, and it will blow you away, and then maybe they do 10 minutes and it doesn’t blow you away so it differs, I think. But it’s just a great format to do whatever you want. I mean it’s audio visual art and it’s as important as all the other visual arts I believe, it’s a brick per brick.

Anthony Nti: I see short films as audio visual arts because you have short films, and video clips, or short films in commercials. I just saw short films as an audio visual art and if you want to make a longer film it kind of starts from the same base, you know. So a short film, I can just speak for myself, for me I see short films as more just telling your story. I see it as brick for brick because I want to do longer stuff. And, and sometimes you can show what you can do in a shorter format and I’m super happy that that’s possible because imagine you only had to make longer stuff or other stuff to be seen, nobody will be here. So, just having a place for shorter stuff. It’s super great but I see it as difficult as you don’t know if you can tell the story. There are people, they can maybe tell a good 20 minutes, and it will blow you away, and then maybe they do 10 minutes and it doesn’t blow you away so it differs, I think. But it’s just a great format to do whatever you want. I mean it’s audio visual art and it’s as important as all the other visual arts I believe, it’s a brick per brick.

What was the budget of your short film ?

Claire Diao: Let’s stay with you, Anthony. Can you please all tell me what was the budget of your short films, so, for example, Da Yie?

Anthony Nti: The budget was a lot of rice, a lot of soup. I had to massage a lot of people, it was a lot of favors. I worked at the Pizza Hut for a year and I made 12,000€, with that and other stuff that I directed. That’s what we did it with, but that’s not the worth of the film, in the sense of a lot of family members just worked for nothing, just because they were family. And the camera guy, PJ, just took a camera and just did it out of passion. So, the budget was passion, a lot of passion and 12k. Which if you know stuff about production that’s not a lot.

Claire Diao: Thank you. Morad, what about Henet Ward? What was the budget?

Morad Mostafa’s Translator: The film is self-funded, when it comes to cash. Because actually, we have two ways to make films here other than through funds or production companies. However, Morad wanted to make the film as soon as he could. So we self-funded the film, when it comes to cash. However when it comes to accessories, costumes and everything else, it was contributions from the members of the cast and crew. And from his own house and my own house. Everybody just did something to make the film happen. And it was made with a very low, low budget. More than you can actually imagine, around 2,000€, I think. That’s how we made the film. And when it comes to the money actually paid and everything else is a contribution. He sees that this is the most suitable way to make the film as he doesn’t want to wait for a year or two for someone to fund the film or to get funded from somewhere and then wait on the film. And choosing the subject and the way to make the film from the beginning can be a great help to make the film with such a low budget. When you make a film and when you write it, you have to consider: “How much do I want to pay? Do I have this or I don’t have this?” We don’t want to wait three years to make a film because he wants to make at least one or two films a year. Also that is something very different from commercial films, which is that he lowered the cost by limiting the crew to the minimum people that he could. It’s less of a load on everyone and he himself as director and producer to have only essential people with actual jobs at the location while making the film. And this is what makes it more simple, more cheap, more easy and, well, and we have a film.

Karabo Lediga: I think in euros, it might be around 15,000€. I have to mention that I had a friend who worked in finance, who took an interest in my talent and wanted to fund my short film as a calling cards. So I’d like to thank him although he doesn’t like to be mentioned by name. So I was quite lucky in that way in accessing that money. But I must say, like what Anthony said, a lot of the cost of the film comes from the charity of really talented people and really kind people. My cinematographer came with an incredible crew, that he had to convince to come and work just after Christmas and New Year’s Eve because that was when the children, the cast would be available. My family also, I shot in my hometown, in the township that I grew up in, and my mother grew up in, because I wanted the authenticity of the story to come from the place where it was set. A lot of the community gave me a lot of access to locations, and to photocopy machines, and to the internet. So I will never really know how much the film cost but it cost much more than what I said. Thank you to everybody who made that possible. Thank you.

A cast of children

Claire Diao: A common point between your three shorts (What Did You Dream?, Da Yie, and Henet Ward) is a cast of children. So could you please let us know how and where did you cast these children, and were they professionals or not? Karabo?

Karabo Lediga: I struggled a little bit with finding the cast because I wanted children who had some experience in acting, or at least had been exposed to the craft, but who could speak English as well as African languages. Specifically Tswana, which is the language that the film is set in, and that I grew up speaking. That’s very difficult because the more access we have to education and to the world, the less indigenous languages we speak. So my casting was going to be difficult because children are not multilingual anymore. You’re either well off and you speak only English, or you don’t have access to the world and you don’t speak English at all. My brother had made a film called Matwetwe, which did pretty well. We shot it in eight days in kind of the structure that I shot my film in. But he went to the National Theatre in the capital city of Pretoria to find really raw theatre actors. So I used the same process to get children out of the Children’s Theatre Clinic. I chose two groups of kids who I thought could speak the language, but didn’t have the same experience in acting. The one who had the most experience had been in the theatre clinic for two years, but hadn’t been on camera. So I workshopped with both groups and ended up choosing three cast members from the two groups. So most of them hadn’t had any experience but we workshopped this group really hard to get to the point where we could shoot for four days.

Trailer – What Did You Dream? from Karabo Lediga on Vimeo.

Claire Diao: Thank you, really interesting. Morad? With a film that also deals with the specificities of specific communities regarding others, how did you cast the child?

Morad Mosata’s Translator: Well, he wanted to make a film about a very special event for women, and he wanted to show this through a little Sudanese girl that has a very special age, which is seven. That’s a very young age to be a girl, and a little Sudanese one living in Egypt and who speaks Arabic. That wasn’t that easy. And also to look like her mom and to do the job. Casting wasn’t that easy because we had had this imagination to have a mother and a girl, and the mother to work as a henna painter, because this is actually the job for Halima before she does the acting for the film. We had a long time to search. Then we found Halima, and she had a sister around the same age, maybe a little bit older. Her sister came to the casting and we worked with her for a while. She was very passionate and very interested in what we were doing, unlike Halima. And then at some point we tried her because she wanted to try to do it. This is how Ward did the film at the end. She had very strong features and her looks were very suitable and very interesting, to be honest. It wasn’t a very easy casting but we think that she had a very good impact on us and on the audience, after.

Claire Diao: For sure. Anthony? Two children that suffer something in Da Yie, we won’t tell the audience. How did you cast them?

Anthony Nti: Me and Chingiz, when we write characters most of the time we are busy with characteristics that are close to us, and so we make a list. There is not really a requirement for us to be in our film, necessarily. My nephew knew a primary school, so I went there and we talked, and went over the characteristics. It was originally Kwaku and Kofi, those were the names of the two characters. I gave the characteristics to one of the professors of the school who was also the kids’ coach. And then the first audition, the first person that came in was this girl called Matilda. The professor said that she was very enthusiastic, she can rap, she’s a great football player, she’s quick with punch lines. Matilda came in and we were just looking at her like, “Okay, I think this is it.” The first one. And then the third one was Prince. And he came, and voilà. So for me the casting, I found the kids literally the first casting day.

Claire Diao: Lucky you were.

Anthony Nti: Yeah, it felt right. We did a lot of rehearsing because they are not professionals. We just hung out. We went to all the locations that we were going to shoot and they knew the places, and I grew up there. So it was just a fun trip, till the shoot.

Claire Diao: Well maybe the ancestors were with you.

Anthony Nti: Yeah, that day I think so, too.

What was the best or worst memory of your shooting?

Claire Diao: Can all of you maybe tell us, what was the best memory of your shooting?

Anthony Nti: Can I go?

Claire Diao: Anthony, yeah?

Anthony Nti: The best memory of us shooting. There are so many memories.

Claire Diao: If it’s too hard, let’s go to the worst one.

Anthony Nti: Yeah, let’s do the worst one. So my film started with a chicken. We wrote that scene and my previous film Kwaku ended with a chicken. I wanted to do more crazy things with the chicken, but I didn’t know how. So we left that scene for the last day of shooting. And so I was trying to look at how the chicken moves and trying to figure out how we were going to do it. And then we found great locations. We started with the chicken.

The first 30 minutes it was going well, and then we lost the chicken. It took us almost two hours to catch that chicken, it was crazy. And the sun was going down, and it was the last shooting day. That was very stretchy. I remember we were trying to get it, and we couldn’t get it. Then there was this lady, she worked as a seamstress and she saw us struggling try to catch this chicken. She went to catch it and literally five minutes later was like, “Here. Take your chicken and get out of here.” After that I wanted her to be our chicken consultant. But that was the worst memory, running after a chicken for two hours to try and finish the shot.

Claire Diao: The final memory. Maybe the chicken went on Karabo’s set. Karabo, what was your worst memory on your shooting?

Karabo Lediga: It is always losing sun. We were shooting anamorphic, this lens was showing all of these beautiful flares, and I wanted the dream sequence to have this magical feel and the anamorphic was going to naturally give us these flares. And we’re shooting on the Ronin, it’s one that my brother and his company owns. They bought like really messed up equipment, and it always kind of breaks. And the sun is going down and we are not getting the shot. I literally ran to the gate of this house and we’re not getting it, and the clouds are just hiding the sun. I was like, “Oh no, we don’t have any more days!” And then, literally magically, the sun just popped out of the clouds and the clouds moved away from the sun, and we had this magical moment when the flares were coming up. I think it was for 10 seconds, and then the sun went out. That was really cool. And a good moment? I wrote long scenes because I wanted to push the cast, and I wanted to push myself. In cinema, in western cinema, they say the scenes shouldn’t be too long, don’t be verbose. But in my upbringing and my culture we talk a lot. Whether there’s death, or whether there’s weddings, they’re long conversations. I wanted to have to play with long conversations, but I had three kids who had never acted in cinema at all. And they had this favorite scene where they’re stomping the blankets. How we wash our blankets is in these little metal baths where you stomp and stomp. It becomes a time for gossip because you’re stomping the dirt out of these blankets. I was very nervous. They had been going on for too long. They’re kids, so they can’t be on set for long. Literally when we said action, they got the dialogue word for word. My continuity specialist and my script supervisor were like, “What?!” It was magical. They seemed like they were having a conversation, ancient and present and futuristic. So really good times shooting this film. Not many bad moments, but the sun will give you bad moments, even if you’re not having any.

Claire Diao: Morad? Did you have more good or bad memories? Can you pick one to tell?

Morad Mostafa’s Translator: I will start with this, he doesn’t have bad memories. Sorry guys. He said that he took it as a challenge that he had to make the whole film in one day, and that the film had to be shot during the day. Making the film in one day was successful because of his experience as an assistant director. Which I can confirm that he made this as an assistant director much as a director. By the end of the day the OP was very tired, he couldn’t pull the camera anymore. Morad interfered and took some of the shots himself and worked as a DLP, as well as a director, and an assistant director through the whole day. So, no, he doesn’t have any bad memories. It was very challenging and very hard, but at the end of the day he made a film of 23 minutes in a very challenging time. So, it’s just a very good memory. The whole shooting day is a very good memory. Also, the actors and the actresses, we had so many rehearsals, so they were really good. They made it more easy on him. They were improvising on set, they were like, “We are a part of this place.” So that made the day more easy. He didn’t give many directions to them because they were really good, and they were unified with the place. So he was really just taking the shots and changing some small details.

What genres and stories do you enjoy working on?

Claire Diao: Thank you. So now we know that if you want to work a lot of hours you go with Morad, if you want to fight with animals you go with Anthony, and if you want to fight with the weather you go with Karabo. So we have a few questions from the audience. For example: As a filmmaker, what genres and stories do you enjoy working on? Anthony?

Anthony Nti: First I wanted to say two things. So, Morad, you shot the whole film in one day? That’s crazy! And Karabo, when you were here in Clermont and I saw the film, we talked about the scene with the stomping. To this day the scene still sticks with me. And that the kids did it just like that, that’s incredible. I’m learning new stuff, it’s really nice. For me, I can watch pretty much anything, but films that have moved me or touched me were films that visually had a voice and an undertone in their subject. So they were telling something about the society, but it wasn’t all up in your face. It was entertainment meets trying to say something about the society, but in a very beautiful art form. Films like Do the Right Thing, Touki Bouki, and Killer of Sheep. These are films that have an interesting visual style, but the storytelling is saying something about the society. It’s not all black and white, it’s gray, it has some funniness. Just a slice of life, but not reality because it’s film. I like when it has a little something extra, I love it.

Karabo Lediga: I have to agree with Anthony, I think that genre is a difficult one. I think it happens after the decisions you make about what story you want to make. It’s all very small. It shines a spotlight on really small moments in life and in the world. It could be any part of society, any country, but it could be a horror about somebody who can’t sleep. Like a horror about insomnia, but they’re living in some wealthy suburb in South Africa. It could be anything about class in the ghettos of Joburg. But it is shining a spotlight on really minute details, so I don’t know if genre counts. But nuance, and subtlety, and small moments mean a lot to me. They say so much when you tell a story. If you focus on character going through “a day in the life of,” maybe the genre is “a day in the life of.”

What does Clermont-Ferrand represent for you?

Claire Diao: So, Anthony, I’ll go back to you. One year the Grand Prix, the next year the jury. This is COVID era, but you’re still a jury member. What does Clermont-Ferrand represent for you?

Anthony Nti: Clermont means a lot for me. In the sense that Clermont was the very first film festival that I came to. That was with Kwaku. I was younger, I had just started film school, I didn’t understand what a festival meant. Because I came here and I saw pews of people who came to see this little film, and talk about it. I really had moments with people and the public. Some people ask you, “So what happened at the end?” People are really intense in the short film format. Clermont made me feel like what I’m doing, the storytelling, and trying to touch people around the world, it’s working. This is a place where you can test it, and you can see what it does. And then, of course, having the film come back later and win the Grand Prix, it’s just crazy. Now I’m with the jury. I feel like I can be with Clermont forever, it shaped me as a filmmaker.

Claire Diao: So you’re a family member?

Anthony Nti: Yeah, I feel like I’m a family member.

Claire Diao: Karabo?

Karabo Lediga: For me, I worked in tv for so long, so jumping into filmmaking with my first short film premiering at Clermont, the love for short film is astounding. I couldn’t have imagined it, even in my dreams. Even what I had googled. I couldn’t imagine looking back at this giant screen showing what I had made with my people from where I come from, and looking behind me and seeing people literally in awe, and people with a respect and a love for film. I think it gives you energy and vibes, the spirit to continue making stories for the world of where you come from. I will never not speak loudly and boldly about this festival, I think it’s everything. The love for film at Clermont, it keeps reiterating it. You are affirmed, it reaffirms film in a way that is amazing. Especially short form. It’s not regarded around the world in that way. At a lot of film festivals, features are the main thing. There’s nothing else that has a love for cinema like this festival. It means a lot to me, and I will forever be grateful for it, and be an advocate and an ambassador for this film festival. Thank you very much to Marie Boussat, and to everyone.

Claire Diao: Wow, thank you for all of these compliments. So, Morad, we have two questions for you. One is about stories and genres you like to work on.

Morad Mostafa’s Translator: Well, he agrees with both Anthony and Karabo, that it’s so hard to decide on a genre for a film. However, he starts with looking into a character, and this character has to make a journey. Whether his journey is on a road, or inside a house, he has to move from one point to another. He comes into the film with something and goes out with another thing, another conclusion, and a difference in his character. Also, multi-plots is, for him, something very interesting. This is also something that goes for the types of films that he likes to watch. To take the characters that you have and to show the subtle tension between them. It’s not always to normalize something between them. He’s always interested in making films where things explode between the characters, and it’s a turning point in their lives. In a very subtle way, without pointing a finger to something, it’s all about what happens in society and that impact on them.

What future for the short film format regarding the COVID pandemic?

Claire Diao: Thank you, thank you. I’ll turn things back around to give my last question. What do you think the future of the short film format regarding the COVID pandemic?

Anthony Nti: I think that because I had just been at Clermont-Ferrand before the lockdown started, that with Karabo and Morad, we are the generation of online festivals. It’s a new way of seeing things. Even though you, of course, want to be in the theater and that cannot leave, I think that should stay, so let’s just hope it comes back. But the good thing about being online is that, even though you can’t be at all of the festivals all the time now the festival comes to your house. This is maybe something in the future that we can combine. Life, but also have a little bit of online for those who maybe can’t make it to the festival. It’s an interesting era.

Morad Mostafa’s Translator: First of all, he doesn’t see that short films have felt much of a negative impact, not as much as the features. Most of the festivals have cancelled their feature sections, such as Cannes, but not the short format ones. So it has not had that bad of an impact on them. The festivals are so important. They continued with the short films, but they did not see the same with the features.

Claire Diao: Thank you so much, I really hope that short films will continue. One last word from Tim?

Tim Redford: Thank you very much Claire. A big hug to all of you, and take care. Thank you very much, it was very interesting.

(transcription : Madelyn Colvin)