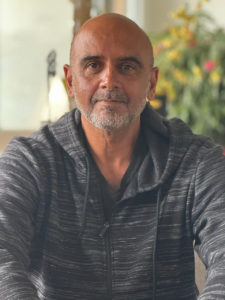

Visiting France, South African activist documentary filmmaker Rehad Desai, who boasts an impressive filmography, granted us a long interview in which we looked at the evolution of his commitments. (Translated into French here)

Rehad Desai

Olivier Barlet: Why did you quit journalism to go to cinema?

Rehad Desai: I quit the academy to go cinema. I was on route for a PhD, I thought “The academy is the place for me, I can spend 50% of my time on my own, projects, research and 50% teaching but soon discovered those days were largely over.’

O.B.: You studied History in London, in Zimbabwe and Witwatersrand in South Africa.

R.D.: Yes, I’m a trained historian, did a master in History, and I was very committed, revolutionary socialist. South Africa fascinated me and a lot of research had to be done.

O.B.: And you were born in Cape Town.

R.D.: I was born in Cape Town in 1963 and left South Africa as a baby, 6 months old. I grew up in exile and by the age of 15, I was convinced that I would join the Umkhonto we Sizwe. My father encouraged me to join that armed wing of the liberation movement.

O.B.: The MK.

R.D.: Yes MK, but I started getting involved in far-left British politics in the Trotskyist tradition, and was convinced by my comrades there that I had a role to play in England. I thought it more effective as a revolutionary in England because I was basically British, whether I liked it or not. I never considered myself or self identified as British, but my background was there. And then, South Africa began to break and you know, the revolutionary potential certainly changed my perspective. So in 1987, I decided to join my father who went to Zimbabwe, and finished my studies at the University of Zimbabwe. And in 1990, we were probably the first exiles to return home, a couple of days before Mandela’s release. I couldn’t bring myself to continue studying even though that’s what I wanted to do, prior to 1994. I just wanted to get involved with the movement to make sure that we would get the best transition possible, it was bourgeois democracy or socialism.

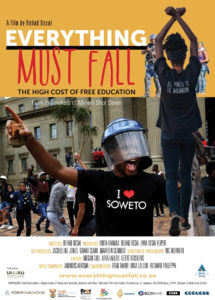

There, going back to the question, mad activism between 1990 and 1994. In 1995 I started my Masters and I’m on track for a PhD and a career and the academy. There were very few black academics. One of my films, Everything must fall, speaks to that gap. My father passed in 1997 just as I was getting into my PhD, and I had a very difficult time of untangling what in my life was what I wanted to do and what was it that he wanted me to do. I realized that I was on a path where in some ways I was competing with him, seeking his approval, I was set to become more qualified than he was (laughs).

O.B.: It’s not easy to have such a father.

R.D.: No. To live in that shadow. But he loved cinema, he knew most of the old films. He became a barrister, he was a performer, he was a man of the people type guy. And that’s why he became very senior in an early age in politics. In exile his stage became the court.

O.B.: Were you in London when he was in Zimbabwe?

R.D.: Yes, he was an alcoholic and he drank himself to very serious medical conditions and he fought his way back. And in 1987, South Africa was bubbling, he decided he was going to quit his profession and return to Zimbabwe. About a year after he left, I joined him to complete my degree in Economic History. My young family joined me there for some time, but my partner found it really difficult. She returned but I stayed on, completed my degree and went to South Africa and the plan was for her to join me, but 1990 in South Africa was very difficult for someone with a young child to consider going there. So that got delayed and delayed, 1994 comes and there was an advert for an historian researcher on a documentary film and I got the job with The Free Filmmakers Collective.

A friend of friend was the director he was make and film and I soon ended up writing proposals, trying to give some intellectual sophistication to what he was trying to do. And that was successful, we raised quite a big help of Soros Film Fund, National Geographic came on board. So I quickly realized I could compete to that level.

A friend of friend was the director he was make and film and I soon ended up writing proposals, trying to give some intellectual sophistication to what he was trying to do. And that was successful, we raised quite a big help of Soros Film Fund, National Geographic came on board. So I quickly realized I could compete to that level.

The masters was important for me because, you know, I am a black man, and I grew up on difficult circumstances and exile so, with the drinking and the depression… The masters gave me the confidence and my directing started out as a sort of a current affair journalism, which in many ways was the path of a lot of filmmakers… There was a space and a public broadcaster then to do what we call “inserts”, current affair programs. My advantage was that I had a perspective on things. Whether it was Mozambique or Zimbabwe, I found it much easier doing stories about the neighboring countries, because at that time, in 97, there was still a strong body of opinion that black people couldn’t govern themselves. And, there’s this sort of fine line when you’re making a political critic of the transition, so I did some stuff and got some complaints to the public broadcaster about me being a communist and stuff, so I thought “Yeah, I’m doing the right thing” (laughs).

But it is hard work, to produce, to live when you need to produce a short piece whether it’s six-seven minutes, ten minutes, on free-to-air TV in South Africa, very few weeks… I did quite a bit of stuff for e.tv headed by Eddie Mbalo for a couple of years. I was given a platform.

O.B.: He became the chairperson on the National Film Video Foundation.

R.D.: Yes. He was a comrade, you know, politically-minded people, but that space gets commercialized over a new channel… The window of opportunity is always very limited before they become commercial.

O.B.: You’ve never worked for SABC?

R.D.: Yes, I produced and directed a few pieces. My first piece was on the Southern communist party. It was called “SAPC on camera” we made a critic of the communist party and how Nelson Mandela and Thabo Mbeki were insisting on a new economic, neoliberal path for development, and how they came down on the SACP to close critical space down, and the meek reaction of the communist party to it. You know the triple alliance: the communist party, the trade union and the African national congress. In those situations, you either raise your head and it gets chopped off, or you keep your head in the sand. I concluded that the party was keeping its head in the sand, and that led for me to get the by-line on the front page of the left-leaning Mail & Guardian newspaper. I took that position.

O.B.: A radical point of view.

R.D.: Yes it was at the time.

O.B.: Would you say you stayed by there?

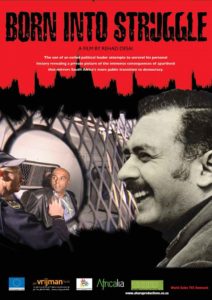

R.D.: Yes! So, doing these pieces, there wasn’t an awful lot of money. I was a one-man show. I was given an office inside the trade union federation, the big one at the time before it split. Thanks to an Italian foundation money, I didn’t pay for my office. I was able to make things work but that was very tiresome, and I realized “Wow, let me start doing TV half -hours” docs, did a few of those, some sort of investigative journalism, then was pulled towards TV hours. I did one piece on Jörg Haider called Dilemma, based on a parallel between my history and that one an Austrian woman, and the child we had together, who was considering going back home, back to live in a fascist country. And then, I really enjoyed the creative process and tried to make it as creatively as possible. I developed a film language for myself and that led me to a more personal piece, which I got a lot of acclaim for. It’s a signature film in many ways, Born into Struggle.

R.D.: Yes! So, doing these pieces, there wasn’t an awful lot of money. I was a one-man show. I was given an office inside the trade union federation, the big one at the time before it split. Thanks to an Italian foundation money, I didn’t pay for my office. I was able to make things work but that was very tiresome, and I realized “Wow, let me start doing TV half -hours” docs, did a few of those, some sort of investigative journalism, then was pulled towards TV hours. I did one piece on Jörg Haider called Dilemma, based on a parallel between my history and that one an Austrian woman, and the child we had together, who was considering going back home, back to live in a fascist country. And then, I really enjoyed the creative process and tried to make it as creatively as possible. I developed a film language for myself and that led me to a more personal piece, which I got a lot of acclaim for. It’s a signature film in many ways, Born into Struggle.

O.B.: Which is your own story.

R.D.: That’s my own story and it’s really, in many ways, a letter to my father. And that was the first sort of film in the South African documentary genre which foregrounded the personal background and the History. It was very popular in South Africa, in a lot of festivals, first film which broke a lot of rules, some of them I was not aware that I was breaking, but with a tremendous amount of freedom.

O.B.: Did you break the aesthetic and the thematic?

R.D.: Well, yeah, , but it was hard to do an honest film about the impact of my family, my brothers in particular who were maybe at the time I thought more psychologically impacted by the life of exile and the lack of parenting of my father. I tried to deepen the psychology and the criticism which could be made was I was pathologizing . The ending was a bit too neat, but I felt that I couldn’t tell their stories without characterizing myself, so I turned the camera on myself. And it also became a bit of a three-generational story, with my relationship with my son and how we repeat those patterns.

I had already made some international reputation among broadcasters. Before that film I produced and I was heavily involved in the production of a film called a Miners Tale . That was in 2002, I had a background in HIV prevention work. And as I had this relationship with the Trade Union, illegally, they gave me access to over a hundred HIV positive mine workers. I started interviewing them and to cast. For the story I was trying to find an HIV positive miner who was brave enough to go home and tell his family, his wife, and his elders. That broke quite a bit of ground because we exploded that narrative around condoms, and the importance of the status of women and men in rural Africa, the ability to breed and what do you do in these circumstance where migrant labour is pervasive… So there was a confrontation he has with his village elders, the head of the village, his uncle, about whether he sleeps with his wife or not. That got translated into fifteen languages, and became a forty-minute film instead of a TV half-hour. So I went on from there to do the family film, the signature film. Why did I continue? Well, I suppose, yes, there was some level of success, it kept me human, it kept me rooted, putting myself in others shoes and then going on to make other films about other people. It kept me psychologically well, you know, as well as I could be. You are always a work in progress when you come from a dislocated family and political background together.

O.B.: Was this approach a kind of therapy for you?

R.D.: It was very cathartic, it was described by a critic called Muff Henderson as fourth cinema, she comes from the movement, became an academic, she is a well-known writer . You know third cinema, of course, this is where you still see cinema as a weapon. I think she coined the phrase, I am not sure, have you heard of it before.

O.B.: Fourth cinema? Yes.

R.D.: So how do you understand it?

O.B.: As I understand it, cinema is no longer a question of being militant for a cause but to get a new way of writing, a new way of seeing ourselves.

R.D.: Yes, we we’re turning the camera on ourselves. To validate personal storytelling. And I was quite taken with this development a few years earlier. It was in a festival in Denmark, an old film on family where the emotive truth was something so powerful, something so maligned in the academy and it wasn’t really recognized. Part of my masters was looking at whiteness, and it was difficult, because as an historian, with a discipline like social science, humanities and in particular film, you’re required to be conclusive, where I realized looking at these things you can only be substantive, and the discourse was incredibly powerful. I started getting an inkling of the power of film really being that emotive truth that… our values and our emotions are one of the same things, they sit you know, life science then goes on to tell us they physically occupy the same part of the brain. At political level you’re not going to get people to act unless you are able to move them emotionally.

O.B.: Would you say that period was a step to something else? To something new in your development?

The Bushman’s Secret

R.D.: Yes. It certainly was, it was the film that I went on to direct and produce with my partner Anita Khanna who has similar political direction, inspired by The Bushman’s Secret in 2006. I got an invitation to Cannes. I didn’t realize how important it was for my career or what it meant.

O.B.: What made you go to the San people?

R.D.: It was because of my blood, my mother. My father always used to tease my mom, my father was more middle-class bushy Indian, quite privileged. My mother is the typical colored, very mixed heritage, we got Bushmen blood in our line, but there’s a shame. I remember my mother’s birthday, they asked me to talk, and I spoke about our heritage and how her father was one of the first black member of the South African Communist Party. It was a white party for many years and he joined it in late twenties. And the Bushmen heritage. And my aunties were horrified that I could mention these things, that I shouldn’t be talking about these savages! At that stage, I began to understand the power of Indigenous thought and culture. And a little company of bio-pharmacists came across the Hoodia plant in 1930s, which if you took it naturally, helps to hunt two or three-days without eating. This company sold it to Unilever and Pfizer got involved and all of the sudden tens of millions dollars were heading into this very small hunter-gatherers society… The historical denial of the heritage of Bushmen blood within The Cape colored is connected with the hierarchy of oppression, the impact of Apartheid thinking, etc.

O.B.: An alternative to The Gods must be crazy!

R.D.: Yes! Very different! It was a very positive affirmation of that community. I mean, I grew up with Gods must be crazy and found it really funny. Then, at of 15 or 17, I realized how deeply racist this shit is… To the expense of wary, egalitarian, human, vulnerable population being hunted and exterminated by colonial powers and the colonial mindset. Actually, I worked on a off shot of this project about Bushman who was killed breaking into an off-licence. Meanwhile, the police justified this in their own terms, like they got the right to do it, according to an Afrikaans saying “Shoot the vermin dead” basically. We did a short investigative journalism piece, which got voted for the best investigate piece of the year.

O.B.: So this look at the Bushmen people was important for the following of your career.

R.D.: Yes, it was important. This was the first film I did with Arte. This was the first film I pitched. It was a tough film to make, a confrontation with the local farmers. I did a 80 minutes cut, but it was very conventional, you know, scene by scene, and it didn’t have the punch I wanted to make. I wanted to say more, but I wasn’t confident enough, I was with one of our best documentary film editors at the time, she was fierce and insistent, so I let her have it her way… I then developed a relationship with a Dutch editor, who came over for Ten years of democracy,. I then asked him to come and recut the Bushmens 80 minutes film, because I found it lacked dramaturgy and I felt a bit ethnographical. We cut it down to 64 minutes and I’m really still happy with that. Yes, it’s my first film that I was making as an emerging filmmaker. The community loved the film, they used it for many years, with hundreds of DVDs, using it to give some coherency to their world view very distinct from the western enlightenment mindset. At that period, there was still a cohort of commissioning editors in Europe with a sort of “this is the way African films must be done” the ethnographical way.

O.B.: And then you went to a confrontation of what is politically happening in South Africa…

R.D.: Then I started developing more confidence and being able to sort of be more critical of my own work. I was still someone who was an unconditional but critical supporter of the National Liberation Movement and the ANC, historical, progressive and so on. And then, things happened which took me in a different direction.

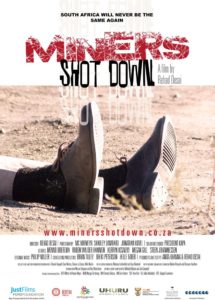

O.B.: How did you come to do Miners Shot Down?

O.B.: How did you come to do Miners Shot Down?

R.D.: I had a relationship with the Ford Foundation which was supporting the Tri-continental film festival I was running: cinema from Asia, Africa, and Latin America. They called me and asked me to do a film about extractivism in the global South, wanting to give me enough money to research this project properly. We agreed on 60 000 US$. So much money to develop a documentary film, I’ve never had that in my life! I went to Mozambique, to look at the Brazilian companies, to Zimbabwe, etc. but I couldn’t find a strong enough story to carry the issues. I ended up at a quite militant workshop of the Bench-Marks foundation on social responsibility and I had this idea to follow the platinum minerals in Southern Africa. There was a strike there, a completely dystopian situation in the news. Two policemen were killed and three mine workers were shot in the first big confrontation with the police. Six mine security staff confronting 2000 miners got overrun, and got killed brutally. Journalists were scared of the site and it was difficult to get there.

Back to that night, I said “Listen, this is the story I want to follow, the strike, because it’s next door to the biggest black owned platinum-mining company and it really shows the issues I wanted to speak about: who’s benefiting from this platinum.” I got home, watched the news and a person I profiled in earlier work is the new leader of the South African Communist Party, the guy had a very close relationship with the general secretary of the national union of mine workers, they’re on TV saying how these workers are suicidal, tribalistic, criminals… dehumanizing them. I go back there the next day, filming, it was difficult. The Next day I didn’t go. I’m glad, maybe I would have been probably more traumatized then I was by the event, that day killed 34 mine workers. And I went into campaign mode, people didn’t really know I was making a film, but I got to spoke to the minority trade Union, and they were much more sympathetic to the unofficial strike than the majority union the National Union of Mine Workers.

I also managed to get this more militant union in touch with a legal NGO and I managed to convince a British lawyer who was involved in the Bloody Sunday massacre in Northern Ireland commission of inquiry to come over. And he was brilliant, the minority union loved him, he was from a mine workers family, his father from silicosis, a mine worker’s disease, and we managed to get the families of the victims representation at the commission of inquiry. So, my thing was “Oh, there’s going to be this commission in a few weeks, we’ve got to get the victims and the smaller union represented, we have no experience of this, we can’t use these big legal NGOs which all have a close relationship with the ruling party, we need a much more independent NGO”

Through that I got very quickly access to forensics reports and footage. Again, this was technical illegally, , but you can only see it once it’s in the public domain. I saw footage the police had released. I couldn’t show much of it in the film – it was gruesome, they did some terrible stuff that was not in the film, and it was very upsetting to see what machine guns do to people, chopped up bodies… It took me a couple of months to be able to watch without getting upset, once the edit started, we went on to decided what to do, “Fuck it, I’ve got to get this footage safe just in case there’s restriction orders on it… I’ve sent it, couple of places around the world’’. Once we started editing, which was probably about six months after the massacre, we realized, actually their archives from a number of sources, I had to fight to access all the archives. I fought because I realized how close we are to telling the story largely through the archive, where you’re in, you’re there! It shows all the things unfold. It took me two months before I could stop crying, I just couldn’t. Working on that stuff was just too upsetting. And that was a very big moment for the country, the African National Congress now has turned on the people who put them into power. I had to tell some people I liked listen ‘I’m this side, and you’re that side’ it broke me.

And I realized I had to get politically active again, it was not enough just to be a filmmaker. It took time and many years but we achieved quite a lot as a campaign, which the film was able to root, to anchor, together with the lawyers and after several years we got compensation for families of the slain mine workers and the injured and arrested. Our first victory was making sure that the families were supported by the state to attend the commission hearings which went on for a long time… we released the film before the end of the commission, the commission went on for two and a half years. We brought the film out in 2014 and it was used out in the commission, there’s massive publicity in the footage, and I’ve realized: if you’re in possession of footage that can be used as evidence it would be criminal not to hand it over because there’ is this judicial process going on, you are legally bound to hand the footage over.

So, I managed to secure some important footage, a current affairs filmmaker said to me: “The footage exists, keep going” I said, “I can’t find it.” He says it exists “Dig. Dig. Dig.” I found it within the Al-Jazeera archives, the stuff was absolutely clear on what went down, piecing it together with other cameras, and the police footage painted a very clear picture. We went public with that and we said, “This is what we’ve discovered and we’re handing it out to the commission,” but we had a press conference about that, the fact that we were handing this footage over. The campaign helped a group that became relatively significant because we were the only ones with a clear independent socialist left program . This was before the Economic Freedom Fighters emerged,

O.B.: The EFF of Julius Malema?

R.D.: No that was the Democratic Left Front. Malema is a product of that moment in many ways he changes the political landscape in South Africa, he launched his party in Marikana in 2014.

O.B.: The people in red?

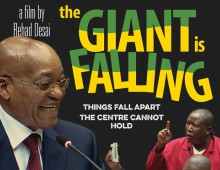

R.D.: Yes . I made a film about his emergence it is called is The Giant is Falling, it’s really trying to allow for a bigger picture understanding of why the ANC and its leaders, Jacob Zuma at the time was its president became rotten to the core . That film ended with the storing of the university students. Their demands were big and expressed a new political imagination. I said to myself: “Wow, if these students in Everything Must Fall continued to demand free decolonized quality education, they are going to come into serious confrontation with our State.” And in the process, if we follow a few of the leading characters carefully, we will see the transformation, the character Arcs will appear. And it was a wager, it was a good wager, because they did change.

R.D.: Yes . I made a film about his emergence it is called is The Giant is Falling, it’s really trying to allow for a bigger picture understanding of why the ANC and its leaders, Jacob Zuma at the time was its president became rotten to the core . That film ended with the storing of the university students. Their demands were big and expressed a new political imagination. I said to myself: “Wow, if these students in Everything Must Fall continued to demand free decolonized quality education, they are going to come into serious confrontation with our State.” And in the process, if we follow a few of the leading characters carefully, we will see the transformation, the character Arcs will appear. And it was a wager, it was a good wager, because they did change.

That was another big moment, it was the first time that we had a generalized national resistance appear, the resistance which was and remains isolated in specific townships or then the big instance of massacre which shifts a few hundred thousand people to the left, away from the ANC. An illustration of this is how my film was used during this uprising, the students are screening Miners Shot Down film before they go out to fight the police. They are saying to themselves look at these guys! They’re confronting thousands of policemen.

I think Everything Must Fall was one of my best films, in terms of craft. We could have been closer than we were with the students, but it was difficult. I had Miners Shot Down behind me so that gave me a certain credibility, but they were like “Fuck all of you. Who are you? We don’t care. How can we trust you?”, and only because I stuck with them for months, following them closely did they warm to me and let me in.

O.B.: You were not recognized as an ally?

R.D.: Yes, but they had democratic structures, so it was a meeting committee, everything needed to go through them and they were other people in the institution who were making a film, or saying they were going to make a film. There were about three people who had shot stuff there, so it was very revealing during the intense moments of confrontation. This was one of the high points, if not the high point, when you get a whole new generation of people involved in act of political reimagination, that’s like 1968. The most interesting character is probably the vice-chancellor who’s from our generation, who’s a former Trotskyist and he’s in this position now, where he’s trying to square it all up, make sense of, provide some sense of coherence to me, you see how he changes during the occupation and resistance , a vice-chancellor roles in a leading university like that turns you into part of the ruling class .

O.B.: And you went on with the confrontation with the power and with the corruption of the Zuma and Gupta system.

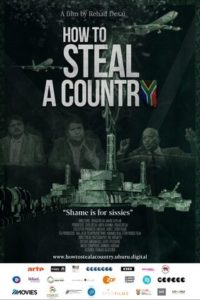

R.D.: Yes How To Steal A Country, there’s a fine line between bravery and fool-heartedness. I was terrified once we’d finish the first six months of edit with Miners Shot Down because of what people were saying, of the way they were responding to, they were like “This is dangerous, this film really unsettle things. You can allow your fear to paralyze you… The Gupta thing… I’ve been involved with Carlos Cardoso, made a film about him and his confrontation and his assassination. How these expatriate Indians were assassinating people terribly in Mozambique, I suppose my first big political film, very difficult, a biopic in a way, it was a quite immature work in many ways!

With Miners Shot Down, I realized that before this project I was always very skeptical, cynical about the power of film to change anything. But I saw what it did in terms of building solidarity with the mine workers, particularly when they went on a big general strike in 2014. It went on for five months, but after two months people were getting hungry, starving and some people died… What are these these guys about, people want to know. And it wins an international Emmy, 28 awards, and then a few later this relatively well known filmmaker approaches me when the Gupta scandal starts breaking. He says, “Listen man, if there’s really anyone who’s going to be able to make this film, it’s you, this is my idea, but let’s do it together.” Difficult codirecting with someone, different sensibilities, but I knew I had to keep it focused, and the board strokes, the first original proposal was “We’re looking at multiple POVs.” I like those films because there’s a lot happening, there’s a lot to think about. But the whistleblowers were too…the world was too small, it didn’t illuminate the project and it was a political project, it was based on this sort of sullen , narrow reactionary nationalism. It’s the only way we can get our hands on this economy corrupting the power, using the power of the presidency.

I thought “Let’s do that”. But I was still editing Everything Must Fall. In the instance of How To Steal A Country I wanted to make a film with a decent budget that we could to show around the country and around the world and to develop the Impact campaign, so the producer of my film also becomes the lead Impact producer. The elites were worried, and even his own state security people were worried about the shenanigans of Pres Zuma. Every film struggles to get finances, money came in quite quick for this. We wanted to do a film which explained the internal dynamics of what happened, with responsibility. You got to take the journalism seriously, but how can you do it in a way which is compelling, entertaining and in the progressive sense of the word entertaining, where it makes you think? That meant looking at the broad strokes following the journalists and their trail of discovery. This was part of an international phenomenon, corruption becoming the norm, you look at the top ten countries in the world, four of them are in Africa, primarily because the elite, the middle-class has been stunted, unable to get into the bourgeoisie, and therefore the State becomes a means for their own economic development.

I thought “Let’s do that”. But I was still editing Everything Must Fall. In the instance of How To Steal A Country I wanted to make a film with a decent budget that we could to show around the country and around the world and to develop the Impact campaign, so the producer of my film also becomes the lead Impact producer. The elites were worried, and even his own state security people were worried about the shenanigans of Pres Zuma. Every film struggles to get finances, money came in quite quick for this. We wanted to do a film which explained the internal dynamics of what happened, with responsibility. You got to take the journalism seriously, but how can you do it in a way which is compelling, entertaining and in the progressive sense of the word entertaining, where it makes you think? That meant looking at the broad strokes following the journalists and their trail of discovery. This was part of an international phenomenon, corruption becoming the norm, you look at the top ten countries in the world, four of them are in Africa, primarily because the elite, the middle-class has been stunted, unable to get into the bourgeoisie, and therefore the State becomes a means for their own economic development.

O.B.: Do you mean the top ten of corruption?

R.D.: The top ten of corruption in the world, there’s France, Turkey, America, and these are more developed economies. So, I tried to frame it in a way where we’d get away from those notion, which I think I spoke about earlier, where this is seen as a black African problem, the big chief syndrome. But there is the french post-colonial theory, this transposition of the bourgeois democracy on all orders with more feudal characteristic, this doesn’t work. It lends itself to corruption. I think there’s something there, certainly, which holds back the development of the mature democracy. for the evolution of democracy itself. it gets complex if you understand this because when the generalized crisis of profitability becomes a major problem for corporations around the world. So KPMG, PricewaterHouse, all those people, they become an international civil service where they mask what’s happening with the economics because they facilitate this international looting, and the banks are willing to turn a blind eye to take shortcuts because these clients are making them a lot of money

. The growth of neo liberalism means that all the governmental agencies are often staffed by the very same characters and personalities in the private sector who they are meant to be regulating. Social democracy has really collapsed in the sense of the third way of Mbeki-Blair-Schroeder in the 90s where we are not going to commit to anything without the growth of the economy, that determines what we’re able to deliver. So, no more promises, no more commitment and then you have a sort of free-for-all situation arising. Corruption then is often the key in a post-colonial setting, and they justify in the in the name of the people, so they justify it in this way, its our turn to get rich and we will do whatever it takes to become so .

O.B.: What is the main obstacle preventing people from understand this situation?

R.D.: Yes it is masked by a long history of oppression and racial divide and urban rural divide. No we have a situation where 50% of our population now lives in cities. Industrial areas with the African National Congress are losing votes badly in the big cities. The only major trade unions are in one federation that are doing are in the public service. They’re in many ways a part of the inside now, inside of the system where the majority is still on the outside, on social grants. People are looking to the party which they think will protect what they have or deliver to them what they haven’t got. A lot of people don’t know who to vote for, or they vote for this new kid on the block Rise Mzansi, which is essentially neo-liberal, but talk as if they’re social-democrats. What I’m trying to say is that there is no political alternative that has emerged which is rooted and giving aspiration to progressive anti-capitalists views. Capitalism is bankrupt and the crisis in South Africa is also a crisis of the international balance of forces, and South Africa is still highly dependent on the import of machinery, so every time there is a growth spurt in the economy, we get a balance of trade problem, which chokes growth. We’re importing more than we’re exporting, we don’t have the foreign currency, our place is determined by our place inside the world economy as a subordinate part…

O.B.: I read you worked on films about water and climate.

R.D.: That’s where I’m going now.

O.B.: Is there a reason why you want to tackle those kinds of subjects?

R.D.: Yeah, I believe the work I’m doing now can possibly help lay the foundations for the 10% of the population to understand what we’re facing which in the next 5 or 10 years will be critically important. We’ve already lost 10 to 15% of our Gross Domestic Product because of climate change. We’ve now got water shedding, lack of foresight and political adaptation, we got serious inequality issues based on one access to the market. Water has becomes commodified, you can afford it if you’re on the inside. So, how do we move away from this sort of extractivist economy? From an ecological perspective we need to shift away from the way we relate to our natural resources, the mantra of economic growth only really ever works for the elite: a justice for all, that requires a more equal, a more caring, a more sharing approach where we keep our natural resources in the commons, or in some instance bring them back into the commons. Unless we begin to develop an ecological consciousness, the disasters that we’ve seen across the continents will become increasingly catastrophic in nature. We need transformative demands to drive a just transition, the fight for free transport, an equitable share of water are examples We need to look at proposals, where everybody gets an equal amount, if not for our society will itself apart in the face of catastrophes. So, that’s where I’m heading now with the latter part of my career, not to say I’m not tempted to do a personal film about my personal relationship to South Africa’s evolving democracy.

O.B.: It goes together.

R.D.: Yes Mozambique won civil war. The film we’re going to do is from one civil war to the other, how did we get there. The Madagascar film is really about green colonialism, green extractivism.

O.B.: Do you feel alone in doing that?

R.D.: Well, internationally I don’t feel alone, there’s some really strong films coming up from around the world. For me, the time of pandemics really talks to the ecological crisis. We have to get on top of land usage and industrial agrifarming, particularly when it comes to livestock. And we have to understand the power of the pharmaceutical lobbying. Strong films are coming out.

O.B.: South-African ones?

R.D.: Yes, there is an emerging consciousness. Zimbabwe is facing massive drought at the moment. It’s unfortunate what happened to Mozambique and the film scene, the film institute… The power of cable pay TV streamers : how we’re supposed to produce for a global audience, it’s nonsense, you just get a really diluted point of view if that’s possible at all, these films are shaped by algorithms so we’re not in a great place in that industry. Strong films are coming out of Kenya.

O.B.: Softie?

R.D.: Yes, Softie was great and God Loves Uganda.

O.B.: From Uganda there is Bobi Wine, The People’s President.

R.D.: Yes. So, I think the documentary genre is definitely moving ahead with less films, but the ones that are getting made and getting out there are stronger than they’ve ever been.

O.B.: We are talking about political documentary films.

R.D.: Yes, they’re the hardest to make! To make well, to make emotionally. Back to my generation, I grew up watching hard-hitting investigative documentaries, and because my father was so political we would always watch them together, but in the 70s they were militant, propagandistic, didactic. So, they certainly made a big shift in African documentary with the help of the global community, with the help of the Progressive Documentary institutes around the world. But part of the problem is, the only money that seems to be really available is for impact films, and all the other beautiful projects aren’t able to get the funding and therefore are compromised, unless someone willing to put 6, 7, 8 years of their life into the project, and you know, there are… (laughs)

O.B.: There are some fools. (laughs)

R.D.: And when they finish, they say “Never again!” (laughs)

O.B.: How would you say you are considered in South Africa?

R.D.: Well, a leading, if not the leading documentary filmmaker in terms of success, being able to attract partnerships, getting film shown, getting the budgets. Needed through the use of various schemes, we’ve got a tax rebate there that has allowed us the last 10, 15 years to go around the world without a begging bowl approach., we’ve got our local broadcaster : « Jump on board, the train’s moving!” You know the “we need you, but we also don’t.” So, that helped in some ways to build a more self-referential cinema but then it has been completely counteracted with the pandemic. Things collapsed in terms of funding levels and only doc filmmakers who were sharp-cookies like me were able to raise money outside of their film funds. It’s much more competitive now with the international film funds with the collapse of much of the public broadcast systems, the budget cuts and stuff, and now in an emerging industry like ours, for producers who are trying to make things happen, to move it or shake it up, they’re not value-driven anymore, it’s just business.

O.B.: With your background, can you go to televisions and say, “I have this project” and so on?

R.D.: Yes.

O.B.: And they’re not going to say “Oh, he’s going to do a disturbing film again and we don’t want it”?

R.D.: Well, certainly in South Africa I’m able to. It has become more difficult in Europe because they’ve turned inwards, they got their own problems now, the more progressive-minded ones say it’s still open, but it’s still limited. So, there’s more of an inward focus, less room for international productions, very hard to get anything up and running. They’re not going to take you on your word anymore, and it’s going to have to be a strong film and a couple of thousand words they want to see. I’m pretty sure the water film is going to be an exceptionally strong film? I’m being successful in getting the sum of money I need. But I’m established enough to be able to make a plan to keep filming things as they unfold, so it’s going to be strong. Hopefully, we will get the Madagascar story working because there’s so little coming out of there, we would be able to get most of the budget in place through broadcasters and funds. The world’s becoming more polarized, so it is a good time for documentary, there is a need for strong perspectives, alternative perspectives and I think the demand is rising again for it, the Palestine conflict has been a really good example of that. Documentary filmmakers are generally tough, the ones who were able to stay the course for 5, 10, 15 years can leverage the resources . Others internally who are not in an established company or don’t have a strong a track record of work often cannot defer fees, so there very little coming out. Have you seen anything coming out of Southern Africa, Kenya, in the last five years?

O.B.: Some films, yes.

R.D.: It seems to be less. Less ambition, less depth.

O.B.: Having your own production company, do you always need to find international funding for your films to get them done and to get them an audience or can you stay in South Africa?

R.D.: Who your film’s for, that’s the problem, the influence. We were able to get that school of thought that developed in the 70s in Northern Europe among commissioning editors who were in documentary: authentic storytelling, storytelling from the inside, building local capacity that was quite missing from the whole French approach. I think there’s been a schism happening between the festivals, who are going for the more artistic films when it comes to documentary, and the broadcasters who are looking for the big impact films and stuff. So, our success is based on the National film video foundation in South Africa that’s functional, and we were able to get development funds there and it’s 15 000 or 20 000 €, it’s something. But really, to develop something that’s attractive for the highly competitive documentary film funds you need the 40 000 € to develop your story, to be able to evoke, develop a text, a trailer and stuff where it begins to jump off the page and looks like an attractive proposition that is going to have some redemptive value. So, if you can get to that stage, you usually are able to then attract three or four broadcasters, some additional funding from people that are not of the main documentary foundations, they have room and the funding things to support films. And you can then get to a position of a 100 000 to 200 000 €, which then means you can produce a film with production values that are expected from the bigger films, the international productions. We know that for a film to work for a French audience, stronger than your general TV French doc, you need 80 à 100 000 €, which is a lot of money. The films have to be as strong as the local stories in terms of craft, and you have to make your audience complicit, it has to be an international story in a way. The audience is somewhat part of the problem.

O.B.: Would you say it’s the same with Netflix and other platforms?

R.D.: No. Those guys, they’re not interested in anything that’s political. Amazon as well. I think there’s a bit of difference for countries who’s got a big footprint among these streamers, they’re a little more flexible on big director or one of the big films that’s doing well on the celebrities… The prospects, the political, social, deep, personal documentaries coming out of Africa are highly limited because the market is so small. They need something because they’ve got an African market surely in Netflix, but Amazon’s just packed up and left. It’s a model which is not sustainable because it cannot continue to grow, you reach a cap.

O.B.: How much percent of your time do you spend to fundraising?

R.D.: There’s mainly the proposal writing and rewriting for different types of funders, and there’s the story develops as well, now I’m in the edit on the Capturing Water. It’s easier to write when you’re very clear about where your story is heading and you have got it in the bag, filmed., it’s easier to evoke more, to think and talk through the structure dramaturgically. Ideally, I’d like to be in a position where I’m spending thirty percent of my time rewriting, attending markets, pitching… Sometimes I can’t spend that amount of time because the only way I can keep the show running, keep the project on the burner means going back to Madagascar, doing some filming and back to Cape Town, off to Mozambique and you only got so much energy and then you do stuff in between to keep cash flow. We have four and a half people in the company and in reality I probably now spend about 20% of my time fundraising, but there’s also pitching and stuff…