Interview with Alimata Salambéré , president of the first edition (1969), by Olivier Barlet

Much is read about the birth of FESPACO. It was therefore necessary to return to its source, to its first president. It was an opportunity to discover the essential role played by the opening film. In 1969, Alimata Salambéré, head of programs at the national television, was 27 years old. Nevertheless, she was chosen to be the president of the organizing committee of the first « Festival of African Cinema of Ouagadougou » in 1969, which lasted a fortnight (February 1 to 15) and became the « Pan-African Film Festival of Ouagadougou » (FESPACO) at its third edition in 1972. (original text in french on the Africultures website)

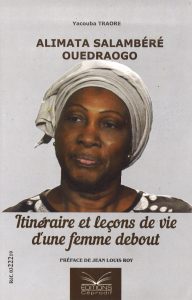

The biography written by Yacouba Traeré, “Alimata Salambéré Ouedraogo – Itinéraire et leçons de vie d’une femme debout” ,[1] provides a better understanding of why. Odette Sanogohh, who was short of time in her post at the national television, had delegated Alimata Salambéré to participate in the organizing committee meetings. François Mifsud also participated as head of the cultural service of the French Embassy in Ouagadougou. While he was principal of the Bouaké high school in Ivory Coast, he had her husband, Emmanuel Salambéré, whom he had appreciated, as a student – by now a jurist,. He therefore proposed the only woman in the group as president, who was elected with great applause. (p. 97)

But Alimata Salambéré would not have been in charge if she was not already known as a star presenter for the television news and for her work as a journalist, showing a strong character that had allowed her to ward off a woman’s fate as a housewife. Her programs « Magazine de la femme », which she already hosted in 1969, then « Nul n’est censé ignorer la loi » (Ignorance of the law is no excuse) marked Burkina Faso’s national radio, to the point that Thomas Sankara later appointed her as Minister of Culture after a tense interview that the book delightfully relates.

During her inaugural speech, she insisted on the festival’s objective: « An African cinema that speaks of Africans, an African cinema made by Africans. (p.16) General Sangoulé Lamizana, Head of State, had agreed to sponsor the festival and embraced its terms, as the following film demonstrates.

Alimata Salambéré insisted that the opening film be Cabascabo, by Nigerien Oumarou Ganda, in which a young African enlisted in the French Expeditionary Corps in Indochina sees his comrades die for a cause that is not theirs and returns home quite distraught. We will read below why this stroke of genius allowed the perpetuation of the festival. O.B.

FESPACO 2019 : « 1969, naissance du premier festival de cinéma africain » from Institut national audiovisuel on Vimeo.

[1] Alimata Salambéré Ouedraogo: the journey and life lessons of a woman of principle” (Ceprodif Editions, Ouagadougou 2019).

Working on the history of African Cinema, I would have liked to verify some information with you because we can read contradictory things about the beginnings of Fespaco, especially concerning the role of filmmakers. In one article, [1] Inoussa Ousseini indicates that Claude Prieux was stationed in Saint-Louis, Senegal, before being named director of the Franco-Voltaic Cultural Center in Ouagadougou.

It is possible.

And that he already had the project to create an African film festival in the same spirit as the Black Arts Festival, in collaboration with Ousmane Sembène and Paulin Soumanou Vieyra.

That’s true.

So, they already had an active advisory role?

I even dare to say collaboration because they contributed to enriching his idea. When you want to see the founding members of Fespaco, I include them: Sembène and Vieyra, even if on the national level it is Upper Volta that had the initiative « with » Claude Prieux to establish this event. Sembène and Vieyra were the first filmmakers who arrived and Claude Prieux based the festival on their films, along with Oumarou Ganda, Mustapha Alassane and Timité Bassori, who also made their films available for free. If he was in Saint-Louis, he probably rubbed shoulders with them and when he was relocated, he found people here who were able to adhere to this idea and he launched out.

From when were they active?

Fespaco was born thanks to Claude Prieux, director of the Franco-Voltaic Cultural Center. I did not know him when he arrived, but I imagine that he had the necessary contacts to pursue his idea. He had contacted François Bassolet, the director of information who ran the state press, Carrefour africain, the forerunner to today’s Sidwaya. There was also Mamadou Simporé, the director of the PTT, Eugène Lampo, from the Ministry of Education (at that time there was no Ministry of Culture), Odette Sanogoh who was in charge of the television (I was then the program manager) and Hamidou Ouedraogo for the mayor’s office in Ouagadougou. They had many meetings and one day Odette Sanogoh asked me if I would be interested in replacing her because she was very busy. I had listened to what she had to say with a slightly distracted ear, but I accepted. The idea was that the films shown at the Franco-Voltaic Cultural Center were only seen by expatriates. There was a film club, but it was seldom attended by Africans.

Like Inoussa Ousseini in his article, Colin Dupré insists in his book on the history of Fespaco on the role played by the « Ouagadougou film club » of the Franco-Voltaic Cultural Center.

It was Bernard Ynonli who hosted it, and he made a film afterwards: Sur le chemin de la reconciliation (On the Road to Reconciliation). I don’t know if they lobbied for a festival but I don’t think that was their concern. It was more that of Claude Prieux, who realized that Africans could not see films made by Africans, and did not find that normal.

So you set up a committee.

Yes, when it started to take form, Claude Prieux invited his boss, the cultural advisor of the French Embassy François Misfud, to participate. During the introductions, he asked me if I knew Emmanuel Salambéré. Everyone knew that he was my husband. But he had been his student in Ivory Coast. I was the only woman. So when it came to electing a board for the different tasks to be accomplished, he proposed my name and everyone applauded. I was afraid but I accepted! We had meetings and we established who could help us. All the services concerned were there: the press, television, Air Afrique had been asked to help with transport, the national education authorities, etc.

Did Sembène participate in these meetings?

No, he was abroad and there were many meetings. He came to the festival as a filmmaker with the films he used to offer for free, which showed his commitment and conviction. He understood that the festival could truly help African cinema.

What was your relationship with President Lamizana?

Lamizana had welcomed us very well and the State financed the expenses that we could not afford, even before the festival, to bring in about thirty films. I proposed to show Oumarou Ganda’s Cabascabo as the opening film: Lamizana was a military man and I was sure that he would be receptive. After some hesitation, everyone finally agreed. He enjoyed the film immensely. He came with his wife, which was not common at the time. I teased them a bit thanks to the joking relationship and we laughed. His aide-de-camp was my husband’s uncle, Kouaka Salambéré: the day after the first edition, Lamizana had his aide-de-camp give 200,000 CFA francs to our committee, a large sum at the time, probably taken from the slush fund, and he made sure that the festival continued.

And who was the secretary general of the festival?

It was Claude Prieux who assumed this role, but then there was a desire to make it more African and François Bassolet succeeded him, followed by Louis Thiombano. In 1970, it took the form of a festival. I was pregnant and I asked to be replaced. So we asked Mr. Mensah, a renowned film enthusiast, who was also the mayor of Ouagadougou. Was it the fact that he was to replace a woman? In any case, he suggested his wife, who was secretary to the Minister of Foreign Affairs. This was accepted and she replaced me. It was then with her that the name Fespaco was given. There is a controversy about who was the first president, but that’s because of the name of the festival. She was not present at the first meetings. I never intervened in this controversy because she was an elder, older than me. As far as I am concerned, I simply did my job when I was in charge.

At the first edition in 1969, you were 27 years old, and you gave a militant speech that was noticed, placing the festival at the service of a cinema made by Africans and that speaks to Africans.

At the time, I was presenting the eight o’clock news. On the opening day of FESPACO in 1969, I was on duty for the eight o’clock news and I had my speech next to my papers for the news. I was « going over it » during the preparation. I was very anxious!

At the fiftieth anniversary symposium in 2019, you insisted on the pan-African dimension of the festival. This was 1969 at a time when African countries were divided between the non-aligned, who had an internationalist definition of pan-Africanism, a conception shared by Sembène and others, and those who preferred a transnational pan-Africanism. How did that affect you?

To be honest, I especially noticed that films made by Africans were not being seen by Africans.

The COMACICO and SECMA movie theatres weren’t projecting any African films?

No, that was not their concern. I was only driven by this conviction, without any underlying political activism. It had become a passion to be able to watch African films.

At the time, there was a great deal of mistrust towards these films. Claude Prieux was transferred to Lomé shortly after the first festival for having screened them. They were reproached for being critical. This was the case for Cabascabo, for example. How was that articulated politically speaking?

I didn’t see it that way. It was on a cultural level, with a passion for what we are, what we can offer and share. That’s what motivated me.

Did President Lamizana have strong positions in this regard?

I don’t think so. In any case, he didn’t express them at the festival.

The nationalization of cinemas in 1970 came about as a result of the demand that cinemas add to the ticket price the new 25% tax imposed by the Minister of the Budget, Garango, who was seeking to replenish the state’s coffers, and known as the « garangose ». The cinemas refused and threatened to close on January 1, which they did, and were thus nationalized on January 4! François Bassolet was sent to France to buy films, but without any knowledge of the business and the field, he only brought back one: Z, by Costa Gavras.

Eventually, inexpensive films were accepted, most notably Hindi films, and the boycott didn’t last very long. This encouraged African filmmakers to produce, in order to replace these images coming from elsewhere that were not part of our culture. These cinemas were run by businesspeople who only thought about their profitability, and we were determined to do it ourselves. SONACIB functioned well for a certain period of time and made it possible to finance the production of Burkinabè films through a tax on tickets, which fed the famous 30-115 account, allowing for the allocation of subsidies at a time when the Ministry of Culture did not have large resources. People continued to go to the cinema and the State also intervened by financing production, which was exceptional in Africa. The State also took on the cost of bringing invited filmmakers from other countries to the festival.

This is still the case, for that matter!

Yes, but partnerships are established that divide the cost. The support of the IOF and the European Union was decisive. The festival bureau went to meet what has become the IOF. I was myself, long after, director general of culture at the IOF, after having been minister of culture under Sankara and then Blaise Campaoré.

How did you experience this change in power?

Sankara had thought that I was capable of defending culture as he understood it, and I told myself that I had to continue with the same conviction in order to consolidate what he had seen in appointing me. As I am not a politician, I do not take sides, but I owed it to him to continue the mission he had entrusted me with. I did not want to leave the place to people who would not have gone in the direction of what he wanted.

If Sankara forced you into this position that you did not want, it is because he knew about your program « Nul n’est censé ignorer la loi” (Ignorance of the law is no excuse), which apparently disturbed many people.

Yes, it did bother. He had been observing me for a long time. The fact that I was at the head of Fespaco in 1983 as a woman and a journalist had impressed him. My children also insist on how novel this was, so much so that I have become aware of my rebellious side!

You are part of the Council of Experts of Fespaco. What is your role?

We intervene if there are questions or differences. There was one between the Minister of Culture and the General Delegate, who were both working on their first Fespaco. I took the liberty of reminding them so, and of the need for complicity between the two of them to succeed and serve cinema. Alex Moussa Sawadogo is very competent and knows the field very well, and his minister recognizes that. I do not believe that you have to be a politician to be at the head of Fespaco. Felipe Sawadogo was also present, and he agreed with my position. He had been appointed secretary general under Sankara in 1984. I had proposed him and Sankara had told me that he was a bit young. I told him that I had no one else and also reminded him of his own age (35)! He laughed and Felipe Sawadogo was appointed until 1996!

The link between the State and the festival has always been problematic: the management of a festival requires the ability to act quickly, without administrative complications. All the general delegates have insisted on strengthening the festival’s autonomy, to no avail.

Absolutely. I don’t believe that this is the particular objective of the current General Delegate, but his work is heading in that direction.

This is the first time that the composition of the selection committee was unveiled, which brought together competent people, and all are pleased with the quality of the 2021 selection. In the future, won’t the challenge be to have world premieres that would strengthen the attraction and international visibility of Fespaco?

Certainly, but for this edition, the postponement from February to October meant that many films were presented in other festivals. In February, we would have been the first to screen some films. If we can overcome terrorism and the pandemic, we will be able to make it!

How did Fespaco find its mark in the beginning? Was it from the beginning the huge popular success it later became?

The attraction was that the public recognized itself in the films. This reminds me of an anecdote: when Gaston Kaboré was director of cinema, the director of Air Afrique was asked to show African films during flights. He agreed, but this was not really followed up! And one day, I was taking a flight and seeing that I was onboard, a manager changed the list of films in order to include an ethnographic film to please me! This was absolutely not our expectation and showed the gap in the understanding of films!

Did you have enough screening venues?

There were six movie theaters in the country and only two in Ouaga, the Ciné Simon and the Ciné Nader. Souleymane Ouedraogo, the projectionist of the Franco-Voltaic Center, managed to install a projector at the Maison du peuple. We must pay tribute to him because it was not easy. He is currently visually impaired. During Thomas Sankara’s first Fespaco, I insisted that the opening be done at the Maison du peuple despite some reticence. I reminded him that this is where Lamizana had seen Cabascabo and this is where it happened!

Interviewed in Ouagadougou on October 17, 2021

text reviewed and corrected by Mrs. Salambéré

Translated by Christian Santa Ana

[1] « Hasard et nécessité dans l’invention du FESPACO », in: Cinéma africain – manifeste et pratique pour une décolonisation culturelle – 1ère partie : le FESPACO : création, évolution, défis (FESPACO / Black Camera / Institut Imagine, automne 2020, 786 p.), p. 117-121.

An English version is availaible in Black Camera.

[2] Le Fespaco, une affaire d’Etat(s), L’Harmattan 2012, p. 89. Cf. <a href= »http://africultures.com/le-fespaco-une-affaire-detats-de-colin-dupre-11325″>article n°11325.